Julie Chamberlain

Julie Chamberlain

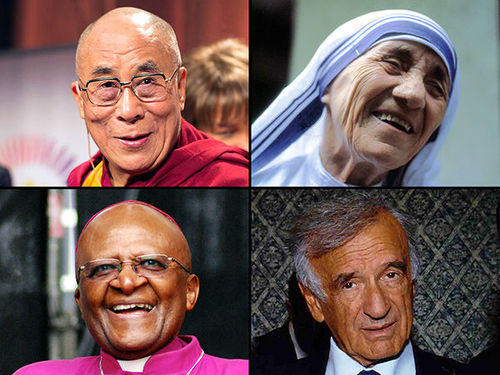

Julie Chamberlain is a Ph.D. candidate in American studies at the George Washington University, and is writing a dissertation entitled “Cultivating Compassion in a Global Age: Religious Icons, U.S. Politics, and the American Moral Imagination.” She was awarded a 2016 Research Travel Grant to study American Catholics’ interactions with and interest in contemporary “religious icons” the Dalai Lama, Mother Teresa, Desmond Tutu, and Elie Wiesel.

Catherine Osborne, a postdoctoral fellow at the Cushwa Center, talked with Chamberlain about her project during her research visit to the Notre Dame Archives this past spring.

CO: I was really interested by your contention that Americans see these figures as “uniquely equipped to mediate engagement with the emerging global South.” Can you give us some examples of how that works?

JC: Absolutely. Just to provide some context, this contention comes from my exposure to several different sets of scholarship—all of which I can’t mention here. One is certainly the work of people, such as my own advisor Melani McAlister, who have pushed the boundaries of religious studies by emphasizing the transnational dimensions of religion in the United States. I was exposed to this work early in my graduate career and have since been fascinated by the ways in which religion shapes people’s sense of their place in the world as well as their relationships with often-distant strangers.

Second is the work of scholars such as Philip Jenkins who have pointed to the growing importance of Christianity in the non-Western world, especially in Africa and Asia. Although my project differs from this kind of research in important respects, it got me interested generally in the global flows of religious influence and the religious leaders who have often represented these particular regions on the global stage.

A third field that’s influenced me is international history, especially as informed by postcolonial studies. One example is Vijay Prashad. Although he comes to different conclusions about the role of religion than I do—for one thing, it’s not his primary interest—his focus on the agency of Third World actors in the post-1945 era has shaped how I think. Overall, I suppose I’m trying to show that these four religious icons were as important to Americans’ changing relationship with the Third World as were, for example, Egypt’s Nasser and India’s Nehru. They harnessed the material and affective power of the United States—seeing its potential for good—while at the same time disciplining it on behalf of the poor and oppressed. That’s a bold claim to make, but I think their absence from U.S. historiography is shocking, given their vast influence.

Obviously, each figure played a different role. For example, although Elie Wiesel was not a Third World leader, I use his example to bridge discourses of suffering in the immediate postwar era to those emanating from the Third World in later decades. Mother Teresa was interesting in that, for some, she was a symbol of the legacy of imperialism in India, while for others she offered a different vision of what it meant to identify with the poor and serve them. Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama embody the image of the Third World leader in more traditional ways, even though their religiosity challenges common perceptions of Third World revolutionaries. Overall, what I hope to provide is a new way to think about the emerging Global South in the late 20th century—in terms of religious geographies rather than just political ones.

CO: Do you think American Catholics engage with these four figures differently than other Americans do?

JC: Yes and no. So much of it has to do with Catholics’ changing place in American culture over these decades, as they became more assimilated, working across religious lines and gaining more power in the public sphere. Most basically what I’ve found is that Catholics took an interest in all of these figures. Prominent Catholic institutions like Notre Dame hosted not only Mother Teresa but also Elie Wiesel and Desmond Tutu. On an even broader scale, it is clear that many Catholics saw these non-Catholic icons as important teachers whose wisdom could enhance both their spiritual lives as well as their engagement with the broader world. What I think this shows is how robust the interfaith movement was during this time, with various groups coalescing around the discourses of compassion and peace that defined these figures. Many Catholics were part of this nebulous “mainstream” or “middlebrow” sensibility that I try to capture. What is striking is that there was so much optimism about the potential for religion to help solve global problems and bring people together—a narrative that has obviously been disrupted in the 21st century.

That said, Catholics weren’t equally enthusiastic about them all, which points to the diversity of the American Catholic experience itself. Obviously, Mother Teresa holds a special place. Even so, some Catholics criticized her—along with like-minded Protestants and secularists—for (among other things) not tackling the structures of inequality that undergird poverty. This included some Catholic nuns who argued that she upheld the status quo. Likewise, some Catholics disagreed with particular things these icons did and said. In fact, Notre Dame’s student newspaper, The Observer, hosted a lively debate about Wiesel in 1985. When one student penned a piece criticizing him for acting as if Jews had a “monopoly” on suffering, other students responded in outrage, arguing that Wiesel was a moral authority for people of all faiths. So, it’s a complicated landscape. But I do think we can draw conclusions about these figures as mostly unifying forces.

CO: Even though Mother Teresa is a Catholic, all four of these figures are from countries that aren’t “Catholic countries.” Are there comparable figures from, say, Latin America, that resonate in the generic American cultural imagination?

I have to admit that I struggled with the issue of whom to include as figures in my dissertation, and partly it ended up being those people I saw mentioned the most in popular and archival sources, often together. For example, the ones I picked were featured prominently in TIME. When Mother Teresa died in 1997, for example, the magazine named the Dalai Lama as her most likely “successor saint.” All four of these figures also won the Nobel Peace Prize between 1979 and 1989, which not only added to their visibility and prestige, but also signaled that their demeanors and tactics were palatable to liberal sensibilities in ways that other leaders might not be. I think this is why they were able to capture diverse audiences in the U.S., including even those who were concerned with the geopolitical implications of their associations.

But this is a great question because I do think that a comparative view—especially with Latin America—could help me articulate in more nuanced ways the kind of sensibility I’m tracking and how it was conditioned by geopolitics. For example, Óscar Romero would provide an interesting case study. On the one hand I think he did not achieve this kind of widespread popularity in the U.S. due to the simple fact that he was murdered in 1980, before the robust development of the narratives I’m calling attention to. On the other hand, U.S. foreign policy in Latin America under Reagan would likely have made it very difficult for him to gain a widespread following among many Americans. However, it is interesting to think about what difference Romero could have made had he been alive in the 1980s. I’ll have to think more about this!

CO: What’s your favorite document that you’ve found so far in the Notre Dame Archives?

JC: I found so many wonderful things, and I’m so grateful to the Cushwa Center and Notre Dame’s archivists for giving me the opportunity. As I mentioned above, American Catholics have been drawn to each of these figures. One collection I really enjoyed exploring was the Monastic Interreligious Dialogue Records, which documents exchanges between Tibetan and American Catholic monastics. The Dalai Lama was a key source of inspiration for this exchange program, not only due to his own pluralistic impulses, but also because his office helped to coordinate the exchanges. The program began in the early 1980s, when Tibetan Buddhists traveled to the United States. American Catholic monastics in turn traveled to Dharamsala and other refugee settlements in India, where they visited with the Dalai Lama and other monastics in Tibetan monasteries. Since I love travelogues—especially when they detail religious pilgrimages—it was extremely satisfying to read the enthusiast reports that Americans wrote upon returning home. They detail the important link I’m trying to suss out between the cultivation of spiritual and political sensibilities.

CO: What did you think of John Oliver’s recent show on the Dalai Lama?

JC: If I had seen the show at the beginning of my research, I would have been taking notes on every word. However, I now realize how common such interviews are. Many Americans have made that long and arduous journey to Dharamsala merely to try and catch a glimpse of the Dalai Lama. So, while I find it interesting that Oliver’s show reaches a new generation, I see it as part of a longer tradition that I trace in the dissertation. I think this points to the remarkable way that he continues to capture Americans’ moral imaginations, despite the fact that he’s not always in the spotlight and has had only limited success in terms of U.S. foreign policy toward Tibet.

Another continuity—seen most clearly in the opening clips of the show—is that many Americans, even while revering the Dalai Lama, don’t necessarily know much about him. However, this is partly why I find him (and my other figures) so interesting! Like the Dalai Lama, many Americans don’t often know where Mother Teresa is from. Nevertheless, they do know they represent the moral good—despite any religious, national, or racial particularities. While the responses of Oliver’s interviewees might be unsatisfying for those who wish for a more religiously literate citizenry, I think they provide insight into the nature of spirituality in the United States, particularly in terms of the continued importance of religion to morality as well as the impact of therapeutic and consumer culture.

The last comment I’ll make is that Oliver’s show is important for reminding Americans that the Tibetan struggle is ongoing. While there was a lot of activism around it in the United States in the 1990s—which I trace—it’s not at the forefront of politics anymore. In light of this, Oliver’s clear identification with the Tibetan struggle is perhaps telling in terms of where many Americans likely stand on the issue, despite official U.S. foreign policy.

Feature image clockwise from top left: the Dalai Lama (Wikimedia Commons, Christopher Michel); Teresa of Calcutta (Wikimedia Commons, Manfredo Ferrari); Desmond Tutu (Wikimedia Commons, Kristen Opalinski); Elie Wiesel (public domain)