By Benjamin J. Wetzel

When John A. Zahm, C.S.C., finished his seminary training at Notre Dame in 1875 and immediately obtained a teaching position there, he joined an exclusively Catholic faculty that received salaries of well below a thousand dollars a year. The student body itself was comprised of only a few hundred young men. More than half of these, moreover, were under the age of 18. There was no large endowment, no football program, no national reputation. In 1875 the University of Notre Dame was like many other Catholic colleges of its day: a small educational institution focused on forming young men through a classical curriculum.

It was only after World War II that Notre Dame began to emerge as a full-fledged university. But in the three-quarters of a century between 1875 and 1950, the University made significant strides toward a more prominent status. A key figure in that transition, argued Rev. Thomas E. Blantz, C.S.C., was John Zahm.

Rev. Edward A. Malloy, C.S.C.

Rev. Edward A. Malloy, C.S.C.

On November 3, 2017, Blantz delivered the Cushwa Center Lecture on the topic of “Father John A. Zahm, C.S.C., in the Founding of the University of Notre Dame.” Blantz, professor of history emeritus at Notre Dame, is working on a book-length history of the University, making him a natural choice for this lecture during the 175th anniversary of Notre Dame’s founding. Rev. Edward A. “Monk” Malloy, C.S.C., president emeritus of Notre Dame, introduced Blantz, and about 110 people gathered in McKenna Hall Auditorium for the event.

Blantz began by acknowledging that the title of his talk would seem “strange” to most people, since the University was founded in 1842 and Zahm was not born until 1851. Yet, he said, Notre Dame could not really be considered a university in its early days, with its limited enrollment and tiny faculty. Even by the 1890s, when Zahm was a leading faculty member, Notre Dame’s president, Andrew Morrissey, emphasized high school education over the needs of the college students. Turning out “Catholic gentlemen” rather than rigorously trained scholars, Blantz said, was Morrissey’s primary goal.

Enter John Zahm. Zahm (1851–1921) was born in New Lexington, Ohio, and enrolled at Notre Dame in 1867. He graduated four years later and entered the Holy Cross novitiate. In 1875, upon ordination, Notre Dame made him assistant head of the science department and assistant museum director. Ten years later, he became vice-president of the University at age 34. In 1898, Zahm was named provincial superior for the Congregation of Holy Cross, an office he held until 1906. At that time, in his mid-fifties, Zahm moved to Washington, D.C. He also traveled extensively, including a trip to South America with ex-president Theodore Roosevelt in 1913. Zahm died in Germany in 1921.

Unlike Father Morrissey, Zahm envisioned Notre Dame becoming a first-class university, on par with Oxford and Cambridge. He repeatedly exhorted students and professors to aim for the highest intellectual standards, putting a premium on the production of new knowledge. Knowing all this would come at considerable financial cost, Zahm nevertheless called for more buildings, higher-quality laboratories, and a better faculty. In Zahm’s view, Blantz said, the expenditures necessary to produce all this would be “worth it.” The priest-scientist ultimately desired Notre Dame to become (in his words) “like some of the great intellectual centers in the Church’s past . . . a recognized home of saints and scholars.”

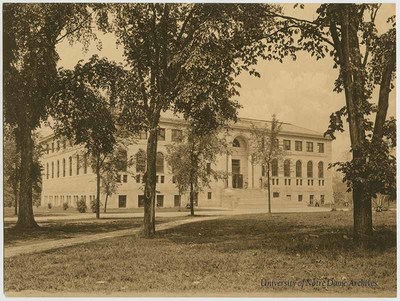

Zahm’s prescriptions were concrete: a proper library was needed, he insisted in 1914, to replace the sorry one on the fifth floor of the main building. At least in part due to his urging, Bond Hall was completed in 1917, the home of the original campus library. An improved faculty also ranked high on his list of priorities. “Scholars and specialists,” not just “devoted religious,” were needed to give students the best training. Each department, he believed, must have specialists able to carry out research and teaching in their particular fields.

In developing a national reputation for the University, Zahm led by personal example. A Dante expert, he collected over 5,000 books by and about the great Italian poet. At his death, his collection was rated the third-best in the nation. Zahm also gained celebrity for his writings, which included 20 books and about as many articles. Sound and Music (1892) surveyed writings on acoustics and interpreted various aspects such as tone and pitch, analyzing how motion might affect sound. The text was adopted in the classroom and reviewed favorably by Scientific American. Zahm’s next effort, The Bible, Science, and Faith (1893), attempted to rebut conservative views of the age of the earth and questioned the universality of the Genesis flood.

Zahm’s most provocative work, however, was Evolution and Dogma (1896), a book that attempted to reconcile biological evolution and Christian belief. He argued that, as long as theology retained the belief in God’s direct creation of the human soul, the evolution of human beings from other life forms was quite compatible with Catholic doctrine. Although the book met with favorable comment from many reviewers, the Vatican found it unacceptable and “ordered it out of circulation,” Blantz said.

Zahm also left his mark on the campus itself. In addition to his work on behalf of the library, Zahm worked hard to see a new science building (now LaFortune Hall) constructed, an Institute of Technology (now Crowley Hall of Music) built, and a new residence hall (Sorin) erected, all during the 1880s. Sorin, it was said, achieved the distinction of being the first residence hall on a Catholic campus to boast private living quarters.

But Zahm’s most important contribution to making Notre Dame an authentic university, Blantz argued, was his support for the establishment of a “house of theology” adjacent to the Catholic University of America. Zahm backed this proposal because it would give seminarians a venue in which to study full time, rather than teach basic courses to Notre Dame students. He also observed that the Washington location would afford priests-in-training the ability to pursue graduate courses at other institutions. Although most of the Notre Dame administration understandably thought that this course would hurt the University in the short term rather than help it, Zahm convinced the superior general to approve the plan. And the plan worked: seminarians in Washington focused on studying, took graduate courses, and some even earned doctorates.

Despite his successes, Zahm also had character flaws, Blantz noted: “He was strong-willed, not easy to get along with, and at times mysterious.” When he would return from abroad, Zahm would take pains to conceal where in the United States he was at any given time. He sometimes wrote under a pseudonym and on one occasion invented out of whole cloth a supposed travelogue through eastern Europe and Asia. On the 1920 census, he described himself simply as a “laborer.” Yet, despite his quirks and flaws, Blantz said, Zahm helped move Notre Dame toward its modern university status.

Rev. James Connelly, C.S.C.

Rev. James Connelly, C.S.C.

A question-and-answer session followed the lecture. The first questioner, Paul J. Browne, asked about the presence of international students in Zahm’s day. Blantz noted Zahm’s trips to Mexico and the southwestern United States where he recruited young men to come to campus. Blantz observed that Notre Dame’s engagement with Spanish-speaking students extends back to Zahm’s time, over a century ago. Another questioner, Tom Kselman, asked where Zahm’s vision of a more prominent Notre Dame came from and what models he would have had in mind. Blantz said he didn’t know exactly what Zahm’s models were, but he noted that European universities might have been an inspiration; in addition, prestigious American universities like Yale had developed graduate programs by the mid-19th century. In a separate response, Rev. James Connelly, C.S.C., noted that Gilbert Francais supported Zahm with his authority as superior general of the Congregation of Holy Cross.

In some ways, Blantz’s lecture dovetailed with the Cushwa Center’s symposium on the 1967 Land O’Lakes Statement held earlier this fall. On that occasion, John T. McGreevy, professor of history and I.A. O’Shaughnessy Dean of the College of Arts and Letters, offered an analysis of Notre Dame’s 20th-century history. As late as the 1960s, McGreevy said, American Catholic colleges and universities did not enjoy equality with their secular counterparts in terms of national prestige, faculty salary, and other metrics; indeed, some observers predicted the most talented Catholic undergraduates would soon forsake places like Notre Dame entirely. The biggest challenge for Catholic higher education in that period, McGreevy said, was “mediocrity.” In such a context, the Land O’Lakes vision offered a more expansive perspective on Catholic higher education, praised greater engagement with the outside world, and promoted Catholic identity while adopting more secular approaches to matters like faculty hiring. Ultimately, McGreevy suggested that Notre Dame’s contemporary academic reputation is due in part to the vision and success of the Land O’Lakes project.

John Zahm

John Zahm

Whether or not one agrees with such a project, the analogue seems clear: just as Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., and the Land O’Lakes Statement helped Notre Dame become more like its most prestigious secular peers in the late 20th century, so Father John Zahm had urged taking a similar path in the first half of the century. Both Hesburgh and Zahm saw the national potential of Notre Dame even as they encountered opposition in implementing their visions. Blantz hinted at the similarity toward the end of his talk. If Edward Sorin was the founder of Notre Dame, he said, and Theodore Hesburgh its second founder, then Zahm deserves to be thought of as a “1.5 founder”—a leader who helped put the University on its present-day path.

Benjamin Wetzel is a postdoctoral research associate with the Cushwa Center.