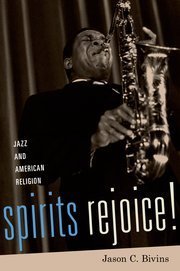

On October 31, 2015, the Seminar in American Religion discussed Jason C. Bivins’ Spirits Rejoice! Jazz and American Religion (Oxford University Press, 2015). Bivins is professor of religious studies at North Carolina State University. Spirits Rejoice, his third monograph, challenges standard divisions between religion and the secular while examining jazz, race, and religious expression in U.S. history.

Cushwa Center Director Kathleen Sprows Cummings opened the session, noting that Bivins’ book discusses a topic that had gone underexplored in past seminars: the arts in relation to U.S. religion. She next introduced seminar commentators Stephen Schloesser, S.J., professor of history at Loyola University Chicago, and Hugh R. Page, Jr., dean of First Year Studies and professor of theology and Africana studies at Notre Dame.

Schloesser began his remarks by admitting that Spirits Rejoice had “enormously challenged and at times confirmed” his own categories of religion. He praised the book’s discussion of improvisation, defining it as the “hybrid between melodies that you know and then the opening up into abstraction” and relating this interplay between “form and formlessness” to his own training as an organist. He further drew attention to Bivins’ “strong claim” that jazz, in and of itself, “is a religious experience.”

Schloesser then commented on several characteristics of jazz and improvisation. Improvisation combines memory with innovation, and the result can neither be categorized nor explained fully through language. Schloesser noted that this abstraction pushes persons toward the incomprehensible, leaving them at times feeling alone and fearful amidst infinity. These observations reveal time to be “provisional” since the present moment never exists—it is already past.

Bivins, Cummings, Page, and Schloesser

Bivins, Cummings, Page, and Schloesser

With this view of improvisation in mind, Schloesser concluded his remarks by posing four questions about Spirits Rejoice. First, drawing on Bivins’ earlier book Religion of Fear as well as theological works such as Rudolf Otto’s The Idea of the Holy, he asked whether jazz provoked fear—either fear of infinity or fear of the Lord in an Old Testament sense. Second, he wondered what insights could be gained if Bivins had narrated the history of jazz in chronological order rather than through the thematic format employed in Spirits Rejoice. Next, Schloesser questioned whether the book overemphasized jazz’s spontaneity and creativity at the expense of tradition. Finally, he wondered whether Bivins had overgeneralized about jazz musicians’ tendency to resist social conformity.

Page started his commentary by underscoring the book’s analysis, which he viewed as a call to reflect more deeply on how to conceptualize and categorize religious expressions, especially among marginalized populations. Drawing on his experiences as an Episcopal priest, blues musician, and theology professor, Page described his comments on Spirits Rejoice as “riffs for a jam session, offered with gratitude from a fellow traveler in the world of music and of academe.”

Page narrated two personal stories meant to highlight themes found in Spirits Rejoice. He recalled a particular concert that he had played with his band when he suddenly found himself overcome, nearly to the point of tears. In that moment, Page recounted, he experienced an “expression of the ultimate,” a transcendent moment that he would never be able to fully explain to members of either the clergy or academy. He next described how he and his wife, while recently co-teaching an undergraduate class on Africana expressive cultures, had led their students through a guided meditation on a song performed by John Coltrane. They had followed this exercise by showing students the website for Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church in San Francisco. The students’ confused reactions, Page explained, exposed the limitations of current academic definitions and disciplines and the need to pay greater attention to living traditions such as jazz—underscoring Bivins’ view that there is a “different way of being in the world.”

Bivins’ book provides readers with a different way of viewing religion and jazz, Page continued, but what should scholars now do to build upon the book’s insights? How can researchers “leverage these possibilities,” he wondered, especially given many academic departments’ and churches’ resistance to certain kinds of research on religion? Page expressed hope that Spirits Rejoice would spark a conversation about how best to bring expressive religious cultures into academic settings without stifling their most distinctive features in the process.

After thanking both commentators, Bivins reflected on his motivations for writing the book. He described how he, like Page, had experienced times while playing jazz when he had “wanted to dissolve into that incredibly pregnant moment.” He wanted to provide a “language,” however imperfect, for discussing these “nameless moments” and making “something lasting out of an encounter with the temporary.” In Spirits Rejoice, he studied how musicians in the 20th century understood their own attempts to variously embrace, challenge, and riff on tradition. He hoped this analysis would encourage readers to think about religion and music in fresh ways, while promoting a distinctive way of thinking and writing in the academy.

Bivins also briefly addressed Schloesser’s and Page’s comments. Referencing Schloesser’s question about chronology, he explained that while jazz was certainly influenced by contemporary developments, many musicians viewed themselves not just as products of their time, but as parts of a larger musical stream that at once flowed forward toward future creativity and backward toward tradition. Bivins saw his own study as an analysis of religion, not just a history of religion, and thus he wanted to understand jazz musicians on their own terms. As for Page’s question about where research should go in the future, Bivins suggested that scholars should “connect, converse, and learn how to listen.”

After a short break, Catherine Osborne (Notre Dame) started off the discussion session by asking Bivins why he shied away from using theological terms, such as kenosis, in the book. Bivins agreed that such terms could be useful, but explained that he was focused on using his subjects’ own terms. Moreover, he wanted “all of the textures and the switchbacks and the loops” of the music “to come through without necessarily encumbering them with too many additional associations.”

Peter Theusen (IUPUI) next built upon Osborne’s question, wondering why Bivins had not drawn more explicitly from figures such as Immanuel Kant and Rudolf Otto, whom he had referenced in the text. Bivins replied that he employed these figures to serve as bridges between the music and academic conversations about religion, with the goal of writing musicians “into the academy” and exploring the “irreducibility of religious experience.”

Comments from Tom Kselman (Notre Dame) and Tom Tweed (Notre Dame) also focused on religious boundaries and definitions. Kselman wanted to know whether some musicians would resist defining jazz as a religious experience, and whether Catholicism’s focus on liturgy and mediated interactions with the Divine challenged Bivins’ empirical claims. Tweed described the seminar discussion thus far as a “tribute to boundlessness” and asked how Bivins would describe his own theory of religion.

Bivins noted that many musicians would push back against his definitions and that few Catholics spoke of jazz as something akin to spirits rejoicing. The point of the book, he said, is not to prove that all people saw jazz as religion, or that all jazz is religion, but rather to show that many individuals have experienced and reflected upon jazz’s religious elements. Bivins also explained how his findings in Spirits Rejoice could fit into previous theories of religion. If he were to formulate his own theory, however, it would be focused on the features of improvisation: “abstraction and embodiment, rootlessness and rootedness, temporality in all its manifestations.”

Winifred Sullivan (Indiana University) asked Bivins to switch gears from defining religion to describing American religion and addressing the tensions between the center and the margins in U.S. religious culture. He replied that jazz music must be seen at once as a product of and protest against the center, and that improvisation in U.S. religion exists in tandem with powers, publics, and bodies.

Michael Skaggs (Notre Dame) picked up this idea of center and the margin, pointing out that individuals may be simultaneously central in some spheres and marginal in other spheres. Bivins agreed, indicating that his focus on marginality is an attempt to recognize the multiplicity of subcultures, not all of which conflict with the center.

David Stowe (Michigan State) raised the topic of the music industry and wondered whether the role of studios, agents, and the like was analogous to institutional religion. Bivins commented that many artists are gleeful about the weakening of the recording industry over the past several decades, but, on balance, conditions for musicians have tended to deteriorate. “The overriding concern of artists is self-determination and authenticity,” Bivins said. “Most want to get out of the space of marginality.” The recording industry’s decline has not necessarily helped artists achieve that creative self-determination.

Kate Dugan (Northwestern) raised a question about space and place, asking how musicians conceive of themselves as moving between space—recognizing that they have to be somewhere to make music—and “non-space,” or transcendence.

Bivins answered by saying that the “musicians want to keep it all in play”—that the “mundane level [of physical reality and place] is absolutely necessary.” He shared the story of how John Cotrane, when he knew he was dying of cancer at the age of 36, was reading metaphysical texts and “wanting to merge with the cosmos” at the same time he would travel to his mother’s Philadelphia home “in a yearning to be with family.”

The seminar concluded with a sampling of music from the book’s listening guide, which is available online at spiritsrejoice.wordpress.com/spirits-rejoice-listening-guide.