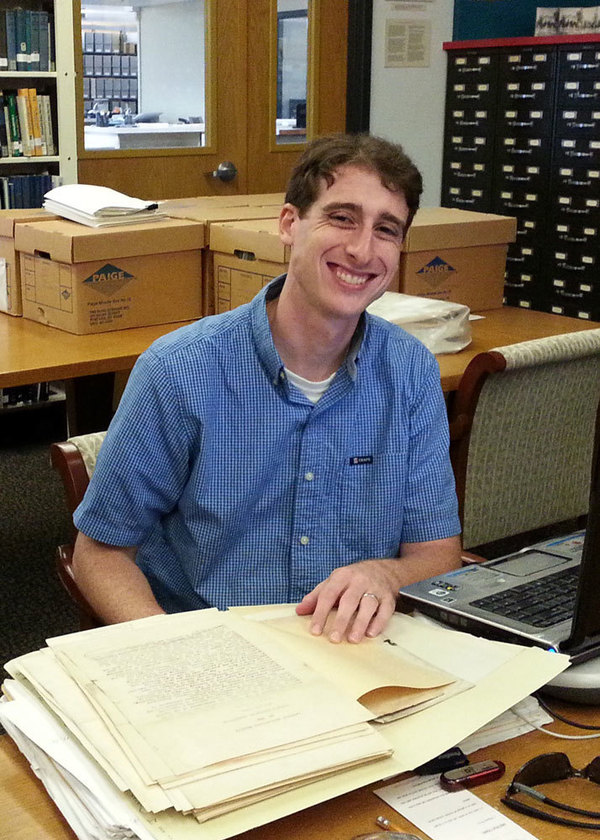

William S. Cossen is a PhD candidate in history at Penn State and a recipient of the 2013 Cushwa Center research travel grant. He spoke with us about his research in August, while he was visiting the University of Notre Dame Archives.

Describe your project for us.

Much has been written on the subject of Catholics as outsiders in American history. What is less prevalent in the existing scholarship is the related question of how Catholics perceived what we might call “the Protestant other.” My dissertation will explore the construction of Protestant identity by American Catholics from 1874 to 1928, the period in which Catholicism became the single largest denomination in the United States. This period also saw Rome officially remove the American church’s mission status in 1908, a recognition of its maturity. The time between Reconstruction and the Great Depression serves as relatively untilled ground awaiting a thorough examination of the ways Catholics perceived their own places in the American nation via their rhetorical and face-to-face interactions with Protestants.

What initially interested you in this topic?

My interest was sparked by a research project in a graduate seminar in antebellum U.S. history. The project required students to pick a book written in the antebellum period and write a new introduction for the text. Given my interest in American Catholicism, I chose Maria Monk’s Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery, an 1836 exposé of a supposedly sordid convent in Montreal. While reading through newspapers and the secondary literature on Monk and antebellum convent tales, I noticed that there was not much discussion at all of Catholic opinions on the Monk episode. Instead of treading on familiar ground that would focus on what anti-Catholic texts could tell us about nativists of the period, I decided to instead examine how the Catholic press effectively redeployed anti-Catholic rhetoric to undermine the claims of Monk and her supporters, ultimately forging a distinctive form of Catholic anti-Protestantism and successfully claiming a greater degree of public space for their church.

Your project covers an interesting mix of personalities and events—namely, the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, the American colonization of the Philippines, and Al Smith’s presidential campaign. How did you make your choices, and do you have a personal favorite?

This has surely been among the most challenging aspects of my project. Encounters between Catholics and Protestants could conceivably be found almost anywhere and everywhere. I had to pick events and figures that would not only illustrate those moments where Catholics could sort out their own place in the nation by coming to terms with the Protestants who frequently conceived of themselves as the normative Americans but would also allow me to draw from the experiences of a wide variety of Catholics. My project, then, works on two levels: internal debates among Catholics on these questions of national belonging and insider/outsider status; and interreligious encounters on a public stage between Catholics and Protestants. Whether at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, in the Philippines during the period of American colonization, or during Al Smith’s presidential campaign in 1928, we see just such dynamics at play.

I think it’s almost impossible to pick a favorite subject at this point! I’ve had a lot of fun sorting through newspapers and manuscript collections for all of them already. However, I am especially looking forward to the challenge of contributing to the ongoing scholarly discussion on world’s fairs of the period, which has been a central subject of a number of important works on the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

What materials have you examined at the Notre Dame Archives?

I found many useful items in the Anti-Catholic Printed Material Collection, the Peter Paul Cooney Papers, the Thomas F. Dolan Papers, the Philip Richard McDevitt Papers, the William James Onahan Papers, and the Notre Dame Presidents’ Letters. But there are so many collections relevant to my research that I am almost certain I will have to make a follow-up visit, which is a welcome opportunity for me!

Have you found any surprises during your research here?

The Anti-Catholic Printed Material Collection contained a large number of items written by Catholics in defense of their church. I intended originally to use this collection to establish a basic foundation of the anti-Catholicism to which Catholics were responding in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but I was pleasantly surprised to find numerous materials that will serve as sources for my dissertation’s central arguments. The Notre Dame Presidents’ Letters collection was also a nice find that contained several examples of Protestants and Catholics conversing with one another on the place of non-Catholics in Catholic schools.

Where else are you conducting dissertation research?

Earlier this summer, I received a Dorothy Mohler Research Grant to pursue dissertation research at the American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives at The Catholic University of America. This fall, I will visit the Center for Migration Studies of New York. I plan to complete my dissertation research at the National Archives, the Marquette University Archives, the Philadelphia Archdiocesan Historical Research Center, several diocesan archives, and the New York State Archives, among others.

What first sparked your interest in Catholic history?

I credit my initial interest in Catholic history to philosopher and theologian Mark Jordan, with whom I was fortunate in my final undergraduate semester to take a seminar in modern Catholicism. The course blended history, philosophy, theology, literature, film, and visual arts. That seminar led me to an already large body of literature that had been previously unknown to me in an academic setting. It was an eye-opening experience that really changed the way I viewed the place of the Catholic Church in the modern world and that spurred me on to pursue my own research on American Catholics.

When did you first discover the Cushwa Center? How has it influenced your scholarship?

I became aware of the Cushwa Center very early in my still-young academic career–probably even before, as I was applying to graduate programs. My introduction to the literature of U.S. Catholic history came primarily through the works of Jay Dolan–the Cushwa Center’s first director–as well as those of Scott Appleby and John McGreevy, both of whom are affiliated with Notre Dame and the Cushwa Center. I wouldn’t be surprised if other younger historians of Catholicism had a similar introduction.

As for Cushwa’s influence on my work, it has been immense. As just one example, four books from Cushwa’s Studies of Catholicism in 20th Century America Series were on my comprehensive exams reading list this past year, and the work of a number of Cushwa scholars has fundamentally shaped the ways I conceive of Catholic studies and frame my own research.