Billy Korinko

Billy Korinko

Billy Korinko is a Ph.D. candidate in gender and women’s studies at the University of Kentucky, working on a dissertation on the development of discourse related to race, gender, and sexuality in American Catholic media from 1917 to 1970. In addition to his dissertation research, Billy is a research assistant at the University of Kentucky helping to develop national studies related to women’s health and anti-violence programs. He received a 2017 Research Travel Grant for his dissertation project. Cushwa postdoctoral research associate Peter Cajka sat down with Billy in September during one of his research visits to Notre Dame.

PC: Can you briefly describe your project for us?

BK: My dissertation project explores the complex relationship between religion, culture, and politics in the United States during the 20th century by examining a largely unexplored pocket of Roman Catholic media, including Catholic pamphlets, newspapers, magazines, radio programs, and television shows. Creators of Catholic media during the early- and mid-20th century paid considerable attention to issues related to race, gender, and sexuality, and repeatedly made the case that Catholic and American values on these issues were wholly congruent. Considering this, my dissertation will illustrate how Catholic media texts should not just be understood as a form of religious self-help literature, but as a part of a larger political project aimed at helping Catholics assume a more central place in American social and political life. In doing so, this project will reveal how religious discourse about race, gender, and sexuality is not static, but always a product of its political, geographical, and historical context.

PC: Why is Catholic media an important source for understanding 20th-century American Catholicism?

BK: All too often, scholars interested in the history of Catholicism pay a disproportionate amount of attention to Vatican documents such as papal encyclicals and letters. While these are important texts, exclusively focusing on these documents does not allow one to understand Catholicism on a more local level. I believe that religion is always shaped by its geographical and historical location, and so if you want to think about religion in a more nuanced and focused way, you have to pay more attention to texts such as religious pamphlets, newspapers, and television shows, etc. Scholars interested in the history of Catholicism do not have the benefit of accessing a database of priest’s homilies or transcripts from church services, so Catholic media is a useful way of understanding the production and experience of Catholicism throughout history. These texts are also important because on some level they are inherently “constructions” of Catholicism; as they are highly curated depictions of Catholics and Catholicism that are keenly aware that their readership was not exclusively Catholic.

PC: Tell us a bit about these Catholic media texts and why they were written.

BK: As I have explored the University of Notre Dame Archives, many questions have stuck in my mind, but one of the most persistent questions has been: How did Catholics in America move from being a group that a century ago was perceived as a threat to the United States of America, to a religious demographic that is now seen as being largely “normative”?

When I have looked at copies of the early-20th-century anti-Catholic newspaper The Menace, the level of animosity towards Catholics seems so strange and foreign to me. While not identical phenomena, I have been struck by the parallels between anti-Catholicism of the early-20th century and Islamophobia today. At the heart of these anxieties are debates about which religious ideas are fundamentally American. So when I think about the wave of anti-Catholicism in the 19th and early-20th centuries, I wonder what has changed.

In the fall of 2015 I remember watching a pope address a joint session of Congress for the first time in American history. I was struck by the image of three Catholic men on screen: Pope Francis in the center, Vice President Joe Biden on the left, and Speaker of the House John Boehner on the right. A century earlier, the thought of the pope speaking to Congress alongside a Catholic Vice President and a Catholic Speaker of the House would have been unimaginable, and would have struck fear in the hearts of those who saw the Catholic Church as an existential threat to the United States.

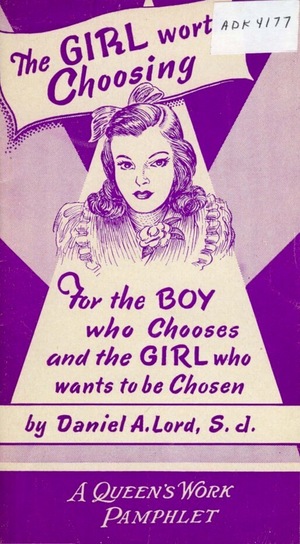

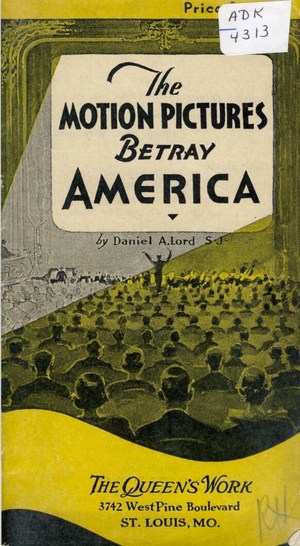

These reflections are what underlie my dissertation because as I have examined a large collection of Catholic pamphlets, I am consistently struck by how clearly the authors of these texts are not just suggesting that following church teachings makes for “good Catholics,” but also for “good Americans.” Therefore I see these texts as not only a pocket of religious self-help literature, but as a part of a larger political project to help confront anti-Catholic propaganda.

PC: What conversation should the fields of American Catholic studies and Gender/Women’s Studies be having? What can they learn from one another?

BK: The field of gender and women’s studies is an incredible space to analyze social inequalities, and intersectionality has been one of the principle theoretical tools for understanding how multiple systems of oppression operate simultaneously to shape people’s lives. While some scholars have produced important scholarship that considers religion an important part of one’s identity, “religion” is not often seen as an essential component of intersectional scholarship like race, gender, sexuality, and class are.

My scholarship is focused on bridging this gap, and helping both American Catholic studies and gender and women’s studies scholars have a deeper understanding of how religious (or non-religious) identity shapes experiences of everyday life. I think a focus on the history of Catholicism in America is a particularly effective way to illustrate the fluidity of social hierarchies related to religion. Catholics in America not only experienced a tremendous numerical growth over the past two centuries, but have also moved from being among those on the margins of American social and political life to its very center. The process about how some Catholics became seen as “normative” American citizens is fundamentally tied to ideas about race, gender, and sexuality.

PC: What resources did you find helpful at the Hesburgh Libraries?

BK: The Catholic pamphlet collection at Rare Books and Special Collections is one of the most impressive collections of Catholic Americana in the country. Additionally, the collection of pamphlets and materials related to the production of these texts in the Notre Dame Archives is vast and could be the subject of a lifetime of work. The work spent organizing, and in many cases digitizing, these texts has been immensely helpful, and without this work I would not have found my way into this project. The hours spent accessing the digital collections from a distance was what sparked my interest in the topic of Catholic publishing, and made me realize that a trip to Notre Dame was essential. But most importantly the staff at Hesburgh Library, the Notre Dame Archives, and the Cushwa Center have been immensely helpful and have consistently made every trip to Notre Dame incredibly rich with great conversation and a tremendous amount of help accessing resources.

PC: Why did you become a historian and a scholar of women’s and gender studies?

BK: I am someone who is deeply troubled by social inequalities, and I think memory and the way history is discussed are deeply political. I remember the discussions surrounding the Obergefell v. Hodges Supreme Court case, and the history of marriage was a foundational part of the debate. Not only was it troubling to me that the rights of my LGBTQ friends (and people I go to church with) were up for debate, the discussion was framed in a way that was littered with historical falsehoods.

The notion that marriage historically has always been comprised of “one man and one woman” is fundamentally false, so from a strictly academic perspective, I found this public discussion woefully ill-informed. But of course, these issues are not abstract or just fodder for some intellectual discussion. The way we imagine history actually affects people's lives. Therefore, when I approach history as a gender and women’s studies scholar, I often consider who is missing. Which voices get silenced or erased? Which individuals and groups are routinely left off the page, and whose work is not maintained by the archives? These questions are deeply important because our collective understanding of history shapes the lives and rights of people today.