Lead Story

The Badin Bible: A Legacy of Firsts

The Bible that the University of Notre Dame acquired last summer and displayed in Hesburgh Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections Room last fall contains all the stories that one would expect to find—from Genesis to Revelation, it’s all there. But for those who know how to read between the lines, so to speak, it also tells a more recent story, one with its own narrative arc and significance for American Catholic History.

The Bible that the University of Notre Dame acquired last summer and displayed in Hesburgh Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections Room last fall contains all the stories that one would expect to find—from Genesis to Revelation, it’s all there. But for those who know how to read between the lines, so to speak, it also tells a more recent story, one with its own narrative arc and significance for American Catholic History.

On October 10, 2014, a crowd packed the Rare Books and Special Collections room to hear from historians Margaret Abruzzo of the University of Alabama and Patrick Griffin and Mark Noll of the University of Notre Dame, as well as Notre Dame theologian Gary Anderson, about this impressive acquisition.

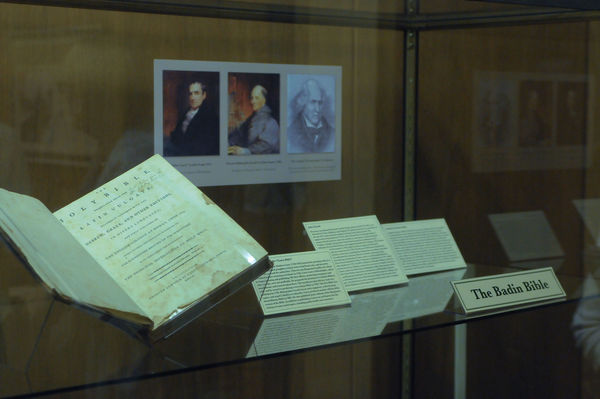

This particular Bible—a three-volume edition that’s being called the Badin Bible after its original owner, Father Stephen Badin—was printed in Philadelphia in 1790 by Mathew Carey, an Irish expatriate. According to its inscription, it was given to Badin, a Frenchman who was the first priest ordained in the United States, by John Carroll, the first Catholic bishop of Baltimore (and the first in the United States), on the occasion of his ordination.

“By tracing the path of this Bible through these three sets of hands and through the United States, this Bible can also illuminate the challenges that American Catholics faced in constructing a church and the structures of Catholic life,” Abruzzo said.

First, she noted, when the Bible was published, the Diocese of Baltimore encompassed the entire United States. While Catholics numbered only about 35,000 and Bishop Carroll oversaw only about 35 priests, the diocese spanned a massive 865,000 square miles. Badin, a missionary who traveled to the American frontier early in his ministry—and traveled around the frontier for decades—would have had the Bible with him in Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio.

Griffin suggested that the Irish-born Carey, the American-born Carroll, and the French-born Badin, all Catholic men who found themselves in America on the cusp of the 19th century, each experienced a distinct perspective on this Age of Atlantic Revolutions. “The different ways they navigated the tensions involved in this age says a great deal about the ways Catholics, and those from the various nations affected, struggled during this period,” Griffin said. “How people understood the struggles of [this] momentous age was not straightforward. It was complex.”

Stephen Badin entered the seminary in his native France in 1789, just as the French Revolution was getting underway. The Revolution’s anti-clericalism forced the seminary to close two years later. “For Badin, the age of revolution and enlightenment was not a place Catholics could live comfortably,” Griffin said. Badin arrived in the United States not long after John Carroll, a Jesuit born in Maryland to a wealthy and well-connected family, was appointed the first bishop of Baltimore.

Carroll in particular faced a complicated dynamic when it came to religion and society. “Throughout his life Carroll would live with the tensions of being Catholic in a society hugely Protestant and traditionally anti-Catholic,” Griffin said. “He was discriminated against in the empire because of his faith, but also lionized because of his polite civility and his affluence.” Carroll believed that religious tolerance was a crucial element in the new, independent republic that had emerged out of revolution. “He hoped confessional differences could fade through faith working hand-in-hand with reason,” Griffin said.

But Carroll also knew that his far-flung flock needed tending, and that included having access to religious resources. When Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey wrote to Bishop Carroll proposing that Carey’s publishing company produce an English edition of the Douay-Rheims translation—the “Catholic” Bible—Carroll offered his wholehearted support (see sidebar).

“In North America, there were virtually no English-language Bibles before 1777,” Mark Noll said. There were, however, Bibles in other languages: Full editions were printed in German and Algonquin, and Catholic catechetical materials printed in New Spain and New France contained Bible excerpts in Nahuatl, Huron, Spanish, and French.

Noll shared a page from Margaret T. Hills’ 1962 book, The English Bible in America (American Bible Society & New York Public Library), with symposium attendees. According to Hills, Carey’s 1790 edition was only the twenty-third English printing of the Bible in the United States. But of those 23 editions, 20 contained just the New Testament—and every Bible printed in the United States up to that point had been the King James Version. So Carey’s decision to publish both parts of the Douay-Rheims translation broke new ground.

Unlike Badin, for whom revolution meant persecution and suppression of the Catholic Church, Griffin said Mathew Carey saw revolution as a promise of liberation. “He had fled Ireland for America because he was a radical proponent of Irish independence from the British crown.” Carey was a Catholic, like Badin, but for Carey, “There could be a place for Catholics in a world defined by republican revolution,” Griffin said.

Ministry on the Frontier

After Badin’s ordination in 1793, his ministry took him to Central Appalachia and the Midwest. Although he was constantly traveling, his home base from 1796 to 1819 was St. Stephen’s farm, now the motherhouse of the Loretto Community in Nerinx, Kentucky. The brick house he erected there in 1816—still in use today—was the first brick building in Marion County. In 1831 Badin built a log chapel in northern Indiana, where he ministered to the Potawatomi in the area. He eventually gave the chapel and the land around it to the Bishop of Vincennes, who in turn passed it on to Father Edward Sorin, C.S.C., for the establishment of the University of Notre Dame in 1842.

When Badin died in 1853, he was buried in the crypt of Cincinnati’s St. Peter in Chains Cathedral, but in 1904 his body was moved back to Notre Dame, where it was interred in the Log Chapel (a replica of Badin’s original, which was destroyed by fire in 1856).

The Rest of the Story

While Badin’s body was buried in Ohio and later Indiana, some of his belongings remained at the Loretto Motherhouse in Kentucky. And it was there, in the vault, nearly 160 years after Badin’s death, that volunteer Carol Pike and archivist Sister Eleanor Craig, S.L., rediscovered the Bible that had been stored away for so long. In Pike’s first visit to the vault, in 2012, while looking through a box labeled “Rare Bibles” with Craig, she unwrapped Badin’s Bible and immediately recognized it as a 1790 Carey edition. The Loretto Community Executive Committee ultimately decided to approach Notre Dame about purchasing the Bible in part because the University had the facilities to publicly display it and make it available to researchers. Fewer than three dozen of the original 471 Bibles Carey printed in 1790 are known to still exist, so the rare nature of the Bible itself combined with the historical significance of the original owner, his gift-giving bishop, and the pioneering publisher, made this specific Bible exceptionally distinctive. The purchase was funded through a grant from the university’s Office of Research and the Hesburgh Libraries.

Kathleen Sprows Cummings, director of the Cushwa Center, submitted the application for the Library Acquisition Grant to the Office of Research. “Notre Dame’s acquisition of the Badin Bible will link Father Badin’s Kentucky home with his Indiana one, and his early ministry as a priest with his final resting place,” she said. “Far beyond the campus connection, however, Badin’s Bible represents a number of historic firsts in American Catholicism. This is a real treasure that will benefit the teaching and research of historians and Bible scholars at Notre Dame and beyond

Learn More >>

Sidebar: Bible demonstrates the problems and potential of Catholic-Protestant relations

Sidebar: A New Chapter

--

This review was originally published in the Spring 2015 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.