HWR Book Review

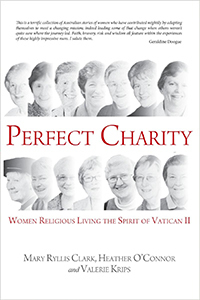

Perfect Charity: Women Religious Living the Spirit of Vatican II

Edited by Mary Ryllis Clark, Heather O’Connor, and Valerie Krips

(Morning Star Publishing, 2014)

Review by Mary Ewens, O.P.

Readers will no doubt recognize that Perfect Charity takes its title from the Second Vatican Council’s 1965 Decree on The Adaptation and Renewal of Religious Life, Perfectae Caritatis, which asked institutes to revise their constitutions according to the charisms of their founders, the signs of the times, and the living of the gospel in the contemporary world. Its implementation amounted to a revolution in the lives of women and men in religious orders. This book documents that revolution, as it played out in Australian communities.

The authors interviewed 14 sisters from 10 Australian communities, two of them contemplative. They are the Mercies, Josephites, Missionaries of Service, Good Samaritans, Loretos, Brigidines, Charities, Presentations, Benedictines, and Blessed Sacrament nuns. Each sister has her own chapter, which is preceded by a brief history of her institute. The narration is enlivened with quotations from the interviews. We learn about each sister’s family background, her call to religious life, her experiences after she enters the novitiate, and the effect of Vatican II on her community and herself. There are helpful footnotes that describe people, laws, etc., that might be unfamiliar to readers.

Five of the 14 entered their communities in the 1950s, and two in 1960. They experienced the pre-Vatican II religious life and an “old-style” novitiate. Five entered between 1966 and 1969, one in ’73, and one in ’95. The first group went through the renewal stages after the Council, and the last one joined a community fully renewed.

These are stories of remarkable women, empowered by Vatican II to fully develop their God-given talents for the good of others. They work combatting trafficking; helping immigrants and refugees; developing new music and liturgies. We meet theologians, a canonist, scripture scholars, feminists, a lawyer, educators, university professors, a canonization postulator, an ecologist and a Lacanian psychoanalyst. One administers priestless parishes. Most are concerned about social justice issues. They welcome Pope Francis’ encouragement to work on the margins, which they have been doing for decades. Many of these sisters end up in leadership positions in their own communities and in a variety of professional or social service organizations, sometimes at national and international levels, where they can be influential in promoting the ideas of Vatican II. But as we are told in its Introduction, the book is not about what they have done as much as it is about the journeys they have taken, as they implemented Perfectae Caritatis and the vision of Vatican II.

Several books have come out since Vatican II that tell the stories of remarkable sisters, from Anne Patrick Ware’s Midwives of the Future: American Sisters Tell Their Story (1985) to Jo Piazza’s 2014 work, If Nuns Ruled the World: Ten Sisters on a Mission. They all tell stories of amazing women empowered by the message of the Council. I doubt, however, that any of them capture the story of pre-Vatican II convent life, the excitement and anguish of renewal, and the current situation—in which many dying communities are ensuring that their assets will promote their mission even after they are gone—the way this book does.

The Introduction tells the basic story of pre-Vatican II convents following cloistral regulations dating back to 1298, the excitement of Vatican II, the pain of implementing renewal, taking off the habit, leaving the schools, losing beloved members, etc. The chapters that follow enable us to feel what it was like to go through all of those experiences, as sisters tell their own stories, often capturing in a few words something that might take pages to explain in cold detail. Taken as a whole, the book gives insights into all aspects of this journey. Some chapters cover pre-Vatican II novitiates, some the “reformed” style. We experience communities divided by renewal efforts, the pain of having friends leave, the excitement of finding new worlds through study and travel, the exhilarating sense of freedom, the God-quest and new forms of prayer, the different theologies of religious life, and challenges faced today by communities with diminishing numbers. All of these are put before us, some in one chapter, some in another. By the time you finish the book, you have a good idea of what the journey was like, both for individual sisters and for religious institutes. Take it from one who has trod the same path: these stories ring true.

The author of the Introduction suggests that these stories have a special quality because they are Australian. She implies that distance from European motherhouses brought a freer lifestyle. Like their founders, these sisters could overcome heavy obstacles and meet all challenges, she suggests. I’m not sure I see these things in the book. Americans, too, were far from European motherhouses, and had to overcome great obstacles along the way. The old rules were pretty much the same for sisters everywhere. The strictures were just as tight in Australian convents as they were in the United States, judging by the witnesses’ testimony here. Yes, there are certainly many small towns in very rural areas in these stories, and work among the indigenous, probably more of it than we find on American Indian reservations.

A major theme that emerges from these biographies is that of the sisters’ drive for education, and the freeing, empowering effect it had on them. For many, attendance at their communities’ teacher training facilities provided credentials for teaching in primary schools. They would seek university degrees later, often attending class part-time while teaching full-time, the same experience we had in the U.S. in the years before Sister Formation. In the renewal years, superiors were happy to support sisters who wanted to go on for further study, and go on they did, traveling to the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and Europe to broaden their backgrounds. You’re interested in human and moral development? Go to Harvard and study with Erik Erikson and Lawrence Kolberg. Liturgical music? Go study in London, attending all the concerts, etc., that you can. Then take a look at what’s happening in Spain, France and Germany. A sister studying in Boston and living with missionary sisters thinks nothing, it seems, of dropping in on their missions in Peru and Chile. I say, extensive exposure to new cultures and enriching travel and study—these are distinctly Australian!

Another theme that pervades the book is that of collaboration. Many of these sisters work closely with the clerical church in their parishes, diocese, and even nationally. Priests are very helpful as the communities begin to read the Council documents. Jesuits in particular run courses for religious, sharing the new theology and the interpretation of the documents. The Introduction suggests that American sisters have irritated the hierarchy by their assertiveness and Australians have not. While that may be true, this book indicates that some sisters are incensed at the injustices done to women in the official church.

For all that we hear about the intent of the authors to show not only the accomplishments of these sisters, but the journeys they took, there is an awful lot about what they have done. I would have liked to see a little more about the spiritual values that are behind and motivate all of these activities. One chapter talks a great deal about the deepening of one’s spiritual life; the others say little about it. I have one stylistic complaint: there is no indentation or spacing to indicate when a new paragraph is beginning.

I would recommend this book highly to anyone who wants to learn about Catholic sisters in Australia (or anywhere) and how and why they changed their lives drastically in response to the Second Vatican Council. It will also be useful for those looking for examples of strong, independent, fulfilled women who embody the highest values and qualities that feminists promote. The authors have shown us the fruits that have come from the invitation to renewal extended by Perfectae Caritatis some fifty years ago.

Mary Ewens, O.P., has recently published a new edition of The Role of the Nun in Nineteenth-Century America, and has chapters in 10 other books on the history of sisters. Her chapter on John Fox, S.J., and the Sisters of the Snows is forthcoming in Crossings and Dwellings: Restored Jesuits, Women Religious, American Experience, 1814–2014, edited by Kyle Roberts and Stephen Schloesser, S.J.