From March 26 to 28, the University of Notre Dame hosted the American Catholic Historical Association’s 2015 Spring Meeting. The event was, to judge from the feedback of presenters and attendees, a great success. Just a few minutes spent mingling during coffee breaks between panels revealed an abundance of new connections, happy reunions, and fruitful discussion among conferees. In terms of both topic and timeframe, the meeting covered an extraordinary amount of ground. Junior scholars (yours truly included) greatly benefited from the feedback, critique, and support of experienced colleagues, proving that the ACHA is making great efforts to foster the next generation of scholarship.

Mark Noll

Mark Noll

The Spring Meeting featured several keynotes and plenary sessions. Mark Noll opened the conference with a keynote titled “Catholic Opinion Concerning Protestant Responsibility for the Civil War.” The Catholic position, Noll argued, stemmed essentially from questions of propriety and authority. Disaffection from political positions held by Protestants, such as abolitionism, followed naturally from the Catholic view that Protestantism was rebellious by nature. Furthermore, the alleged Protestant tendency toward sectarianism—and surely there was no worse sectarian threat than the split of the nation along sectional lines—pushed many Catholics to assign blame for the war to their non-Catholic compatriots. As Noll pointed out, there were several strongly pro-Union Catholic publications that argued for an end to slavery. But in the large view, American Catholics preferred to avoid war altogether. Responsibility for brother-against-brother combat, many thought, could be laid squarely at Protestants’ feet.

In a recap of ACHA’s annual meeting in January that appeared on the Religion in American History blog, Peter Cajka recommended a greater emphasis on historiography at future meetings. While most presenters at this meeting remained within the fold of Catholic Studies, a keynote address by professor emeritus Philip Gleason, “The Ellis-McAvoy Era: The Writing of American Catholic History Comes of Age at Mid-Century” offered a sweeping overview of American Catholic historiography and its enrichment over the course of the 20th century. Gleason argued that between World War II and the Second Vatican Council, the massive flow of veterans—many of them Catholic—to American universities on the GI Bill fostered a new level of education and specialization, planting the seeds for a generation of scholars. The struggle against Nazism prodded the United States, including its historiographical establishment, to a greater appreciation for democracy. These external factors combined with developments internal to Catholic historiography—including emphases on new areas of research like communities of women religious, anti-Catholicism, and mission efforts—to produce a highly professionalized cadre of Catholic historians. Standing behind much of this progress was John Courtney Murray, whose understanding of the early 20th-century Americanist “crisis” led him to support greater affinity between Catholicism and American democracy and religious pluralism. Murray was silenced by Church authorities for his views, which were later vindicated by Dignitatis Humanae, the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on Religious Freedom. Thus, argued Gleason, was the stage set for the self-critical and revisionist histories of American Catholicism in the post-Vatican II era.

Philip Gleason

Philip Gleason

At the conference banquet following Gleason’s keynote, conferees had the opportunity to view excerpts from Chosen (Custody of the Eyes), a documentary-in-progress by Abbie Reese about the Corpus Christi Monastery in Rockford, Illinois. The Poor Clare Colettine nuns who are cloistered at Corpus Christi have worked with Reese to produce a documentary film following “Heather/Sister Amata,” who transitions from life in the outside world to that of a vowed woman religious. Reese’s film will be the outcome of a 10-year collaboration between artist and sisters, and provided not only beautiful images but grounds for an excellent conversation on methodology and the position of the historian.

The interdenominational tensions noted by Professor Noll were reflected also in several panels. The Spring Meeting shone especially brightly in the area of Catholics as Americans, with both Catholics and non-Catholics over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries deciding who was and was not American. In a panel on “Making an American Catholic Century,” William Cossen argued that early 20th-century Catholic support for immigration restrictions fostered racism among Catholics and even reinforced an anti-Catholic hegemony.” Peter Cajka narrated the importance of “conscience” as a justification for belief and action at midcentury. Trevor Burrows revealed the involvement of Catholics in student activist movements, even as those movements eschewed religious overtones and targeted Protestants for recruitment. On another panel, “Catholics on the American Frontier,” Danae Jacobson told the strange tale of a typewriter on loan to—or perhaps illicitly held by?—a group of Sisters of Providence in the Washington territory. The foreign sisters played a conflicted role in the American program of native assimilation, and their conflict with a federal agent over the modern technology of the sewing machine provides fertile ground for an investigation of power on the frontier.

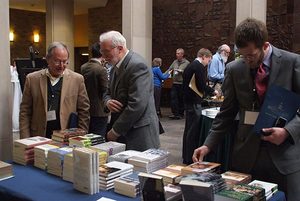

The conference book table featured titles by many ACHA members.

The conference book table featured titles by many ACHA members.

Samuel Jennings argued that French missionary work among the Comanche of what is now Oklahoma helped invigorate modern French Catholicism, which helped revitalize at least one religious order that had been suppressed earlier in France. A third panel, “Mission, Evangelization, and Propaganda,” investigated the nationalizing efforts of several Catholic and Christian organizations. Massimo di Giacchino drew out the similarities and differences in the approaches of Catholic Bishop Giovanni Scalabrini and Methodist Bishop William Burt as both helped Italian immigrants assimilate to American society. Beth Petitjean’s presentation on Antonio Zucchelli, an 18th-century missionary to the Kingdom of Kongo, argued that Zucchelli’s disillusionment with a mission society largely closed to his converting effort challenges the notion of the heroic, successful missionary establishing syncretic forms of Christianity around the globe. Charles Gallagher’s presentation, “A Nazi in Boston,” examined the continual efforts of Francis P. Moran, a local leader of the Christian Front, to pass on Nazi propaganda from German diplomat Herbert Scholz. The Christian Front, which was inspired by the anti-Semitic and anti-communist ravings of Detroit’s Father Charles Coughlin, helps exemplify the complex historical relationship between global Catholicism and its adherents in the United States.

Maggie McGuiness and Jim Carroll catch up at ACHA’s Spring Meeting.

Maggie McGuiness and Jim Carroll catch up at ACHA’s Spring Meeting.

Several panels also addressed the place of Marian piety in 20th century America. Karen Park presented on Josef Slawinski’s Peace Mural in a panel on “Mary in Cold War America.” The mural, commissioned for the altar at the Our Lady of Fatima National Shrine Basilica in Lewiston, New York, illustrates both the perils of nuclear annihilation and the promise of peace ushered in by space-age technology and science. Thus the mural helped Catholics in upstate New York navigate, in Park’s words, “the story of both their worst fears and their bravest hopes.” In a Catholic foreshadowing of the Seminar in American Religion’s treatment of Grant Wacker’s new book on Billy Graham, Kathleen Riley presented the Marian piety of Fulton J. Sheen, the Catholic Bishop known for his massive presence on radio and television over the 20th century. Echoing the importance of devotion to Our Lady of Fatima, who had appeared to believers in Portugal in the early 20th century and who implored the faithful to pray for the conversion of Russia, Sheen’s Marian piety was a crucial component of his anticommunist exhortations in print and on his show, Life Is Worth Living. Catherine Osborne’s presentation on Our Lady of Space, a 1958 painting by Sister Mary Augustine of the Missionary Sisters of the Society of Mary, connected closely with Karen Park’s analysis of the Lewiston Fatima mural. Our Lady of Space helped Catholics internalize contemporary scientific explorations, including space exploration, as part and parcel of better understandings of God. The painting also typified the Catholic notion that Mary reigned over all of creation—a creation that could come to an end in the insanity of the nuclear arms race.

Another panel internationalized the historiography of women, taking the meeting beyond its generally American focus. Keith Egan’s paper on Teresa of Avila portrayed the saint as a prefigure par excellence for the theological schools validated by the Second Vatican Council, reading extensively in the Patristic tradition and introducing an element of mysticism into cloistered life that was lacking before the 15th and 16th centuries. Kenneth Hoyt’s presentation on Hrotsvit of Gandersheim and her writings on martyrdom interrogated the historical split between action and prayer by the martyrs. Finally, Robert Russo brought the panel back to American Catholicism by arguing for the classification of Dorothy Day as a Catholic mystic. Day’s writings on poverty, Russo argued, suggest that her vision was almost other-worldly and evinced “a surrender to the power of love.”

The meeting organizers also made efforts to incorporate presentations and experiences that went beyond panels of papers. Abbie Reese’s film, shown at the banquet, was followed by a roundtable on pedagogy, where panelists from a wide range of institutions spoke to central problems and questions of student identity and engagement with religion as a historical category; Kevin Cawley’s demonstration of Notre Dame’s digital resources and his later tour of the Notre Dame archives; and a tour of South Bend parishes that offered participants the chance to experience local history and architecture.

The impressive breadth and depth of this year’s Spring Meeting prevents a detailed recap, but one way to learn more is searching Twitter with #ACHAspring2015. Twitter users @CushwaCenter, @petecajka, @mbfconnolly, @fracadeddu, and others (including myself, @maskaggs) tweeted some of the highlights of panels. To be sure, distilling nuanced arguments into 140 characters or less is a challenge, but the Spring Meeting demonstrated the importance and potential of embracing this particular platform. For example, historians @Herbie_Miller and @carmenmangion, who were unable to attend the meeting, offered particularly enthusiastic feedback. Even if tweeting a conference is no substitute for engaging with scholars in-person, it has clear benefits for identifying interesting threads of research, new directions in scholarship, and fellow historians who might be helpful collaborators.

This conference recap by Michael Skaggs originally appeared on the Religion in American History blog (usreligion.blogspot.com). It is reprinted here with permission from the author.