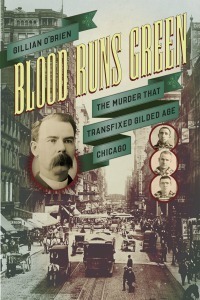

The fall 2015 Hibernian Lecture, held on September 11 in the McKenna Hall Auditorium, featured a presentation by Gillian O’Brien on the deadly underworld of late 19th-century Irish Chicago. O’Brien’s lecture, cosponsored by the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies, was based on her book Blood Runs Green: The Murder That Transfixed Gilded Age Chicago, published in 2015 by the University of Chicago Press. The book examines the murder of Chicago physician and Irish nationalist Patrick Cronin in May 1889, placing the doctor’s death and ensuing legal developments in the context of Gilded Age urbanization and the transatlantic campaign to secure Irish Home Rule. O’Brien is a history department faculty member at Liverpool John Moores University in England and past recipient of the Cushwa Center’s Hibernian Research Award.

O’Brien’s presentation was the first in a series of events during the 2015-2016 academic year designed to celebrate the Cushwa Center’s 40th anniversary and honor the scholarly contributions of each of its three past directors. The lecture’s focus on the Irish urban immigrant experience paid tribute to founding director Jay P. Dolan, who oversaw the Center from 1975 to 1994 and was in attendance for the presentation along with his wife, Patricia.

After an introduction by current Cushwa Center Director Kathleen Sprows Cummings, O’Brien spoke about how Dolan’s embrace of social history revolutionized the study of Irish-American immigration and religion. She described how Dolan’s research on parish life in the Midwest had aided her own scholarship, and noted that she assigns Dolan’s book The Irish Americans as required reading for students in Liverpool.

Humbled and “more than a little daunted” to have been asked to present a lecture in Dolan’s honor, O’Brien began her narrative by describing how, during fellowship research at Chicago’s Newberry Library, she happened upon newspaper articles from 1889 discussing the Cronin murder. Intrigued, yet knowing nothing about the case, she searched for a book on the murder– only to realize that while six works were published for popular audiences in the crime’s immediate aftermath, no scholarly studies of the case had been completed in the intervening 120 years.

Gillian O'Brien

Gillian O'Brien

“As I read more about it,” O’Brien recounted, “it struck me that there were a number of ways in which this was more than simply a murder case.” Revisiting the Cronin case, she argued, offers a new avenue for exploring four key developments in Victorian society.

First, the Cronin story illuminates how Chicagoans triumphantly rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1871, transforming their city into a “place of opportunity, of hope, and of expectation.” Cronin and his contemporaries lived during the period when the balance of power in Irish America shifted from East Coast cities toward Chicago, O’Brien explained, making the rebuilt metropolis into a center for Irish revolutionary activities and organizations such as Clan na Gael. Clan members cultivated a close relationship with Irish-born Chicago Archbishop Patrick Feehan during the 1880s, while local chapters of the Clan, referred to as “camps,” sprang up across the city.

The Cronin murder and its legal aftermath also coincided with a British judicial inquiry into allegations that Irish Home Rule champion Charles Stewart Parnell had supported the 1882 assassination of two British officials in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. News of the Chicago physician’s death thus reverberated well beyond the Midwestern United States and carried the potential, along with coverage of the Parnell Commission, to shape public opinion on both sides of the Atlantic concerning Irish revolutionary violence. O’Brien noted that even Welsh-language newspapers published in Wales carried news of the Cronin case. The fact that the Chicago physician’s death occurred months after London was convulsed by Jack the Ripper’s unsolved killings only added to public interest in the Chicago case.

Third, coverage of Cronin’s murder in U.S. newspapers quickly became exaggerated and contradictory. The case “occurred around the time that newspapers are taking on sensational crime and wanting to write about it,” O’Brien observed, adding that this coverage often made cases into “more than they really were.” Even so, she continued, the Cronin murder was by all accounts a “special murder.” Unlike most murders in Gilded Age Chicago, which usually stemmed from either drunkenness or domestic abuse and thus were quickly solved by the police, Cronin’s death featured a mix of conspiracy and corruption.

O’Brien identified these “layers of corruption” as the Cronin case’s fourth significant feature. Chicago judicial and police officials came under fierce criticism for their incompetence as well as for, in the case of detective Daniel Coughlin, their alleged involvement in the murder.

Having outlined the historical importance of the case, O’Brien next profiled Cronin and his chief antagonist, Alexander Sullivan. Both men were members of Clan na Gael, an ostensibly secret organization committed to advancing Irish freedom through political agitation and violence. Clan na Gael grew out of the Fenian movement, O’Brien continued, living up to the adage that “once you set up an Irish secret revolutionary society, the first thing on the agenda is the split.”

After moving to Chicago in 1873, Sullivan steadily moved his way up Clan na Gael’s leadership ranks even as members remained sharply divided over whether he was a true Irish patriot or simply “a great opportunist.” Cronin, who moved to Chicago in 1882, fell into the latter group and soon after arriving in the city he began to clash with Sullivan.

O’Brien then summarized the Clan’s anti-British activities between 1875 and 1889, which included sponsoring the daring rescue of six imprisoned Irish revolutionaries in Australia and efforts to design a submarine capable of attacking British merchant shipping. She also explained Clan na Gael’s ciphers and hailing signs, neither of which prevented spies from infiltrating the organization and disrupting many of its efforts during the mid-1880s to set off bombs at prominent London locations.

Simmering tensions within Chicago’s Clan organization exploded in the wake of this failed “Dynamite Campaign.” When $100,000 in relief funds earmarked for the families of dead and jailed dynamiters vanished, Cronin accused Sullivan of embezzlement. Cronin was subsequently expelled from the Clan and accused as a British spy, while Sullivan was declared not guilty during an internal Clan inquiry.

On May 4, 1889, the dispute between Cronin’s defenders and Sullivan’s allies culminated when the physician was summoned to an icehouse located four miles from his home, ostensibly to treat an injured worker. The doctor entered the waiting buggy and rode off, never to return.

Chicago’s newspapers kicked into overdrive after Cronin’s friends reported him missing. Various articles explained that Cronin had fled Chicago because he had performed an illegal abortion or was heading to testify to the Parnell Commission that he was a spy. One of the most popular—and outlandish—explanations for the doctor’s disappearance, O’Brien recounted, stated that Queen Victoria had ordered four Neapolitan brigands to murder the Chicago physician.

Two weeks after Cronin’s disappearance, his body was discovered in a sewer north of Chicago. Daniel Coughlin, a Clan na Gael member and the police detective first put on the case, was later arrested for the murder along with four other suspects.

The murder’s mix of conspiracy and police corruption created brisk business for some Chicago entrepreneurs. Wax reproductions of Cronin’s body were displayed in the city’s dime museums. O’Brien also explained that the married couple who owned the cottage where the murder was believed to have occurred charged visitors a 25-cent entrance fee. For another 25 cents, visitors could take home a piece of the cottage’s “bloodied” wood (which the owners had soaked in ox’s blood). The cottage’s visitor log featured entries from nearly every U.S. state as well as Ireland, England, and Canada.

U.S. publications outside of Chicago also drew attention to the Cronin case. Judge, a satirical magazine published in New York City, featured an illustration that linked Cronin’s murder to the Dublin Phoenix Park killings. An illustration in Life similarly referenced the Cronin case, displaying a figure holding a Clan na Gael flag refusing to be stirred into the American “melting pot.” These references to revolutionary activity, O’Brien argued, underscored Gilded Age audiences’ “incredible literary and political awareness” of transatlantic developments.

The murder’s international fame ensured that almost all potential jurors were already familiar with the case and had formed opinions about it. The challenge of trying to seat a neutral jury turned the Cronin trial into the longest-running case in U.S. jurisprudence up to that time. 1,115 Chicagoans were summoned between August and October 1889 before enough jurors, none of whom were Irish, were finally selected to decide the fate of the five suspects.

Alexander Sullivan, however, was not one of the five. Cronin’s friends continued to accuse Sullivan of orchestrating the murder, O’Brien noted, and he had initially been arrested and bailed, but the charges against the Clan leader were dropped before the case went to trial.

In December 1889, the jury announced its verdict. Three of the accused were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment, since one of the jurors objected to the death penalty on religious grounds. The city’s newspapers, in contrast, called for blood. Reporters denounced the jury’s decision as a “travesty” of justice, arguing that only the death penalty provided suitable punishment for such a heinous crime.

O’Brien argued that Clan na Gael’s political and social standing in Chicago collapsed in the wake of Cronin’s murder. The split between pro-Cronin and pro-Sullivan Clan factions lasted until 1900, and the two sides only reunited after agreeing to never again discuss Cronin’s murder. Other members, who had previously viewed Clan na Gael as a fraternal organization designed to help them find jobs, were repelled by the violence and left the Clan in droves. Archbishop Patrick Feehan also condemned the organization.

The Cronin case, O’Brien continued, also influenced Chicago’s police force and newspaper industry. Many officers were suspected of corruption and dismissed from the force, while newspapers embarked on “a whole new era of sensational reporting.”

O’Brien finished her lecture on a mysterious, and ironic, note. After Cronin’s death, she explained, supporters raised $5,000 to erect a monument in the physician’s honor at Calvary Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois. Today, however, only a small marker identifies the location of Cronin’s grave. So who lined their pockets at the project’s expense? “For a man who died largely because he exposed corruption,” O’Brien concluded, “something happened to the money that had been raised to honor him.”