Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., in his office, 1969. Courtesy of Notre Dame Archives.

Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., in his office, 1969. Courtesy of Notre Dame Archives.

At the close of the morning rush hour, local police departments blocked traffic as 18 yellow school buses packed with high school students and faculty caravanned west on New Jersey’s State Route 10. The procession stopped at the AMC East Hanover 12. There, alongside teachers and administrators, the student body from Seton Hall Prep, the Garden State’s oldest Catholic prep school, filed out of the buses and into eight theaters at the complex.

It was an unusual field trip. Every student in the school attended a mid-morning screening of Hesburgh, the 2019 documentary film about Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. Without a connection to the University of Notre Dame, where Hesburgh served as president for 35 years, and apart from some pre-show Googling, it’s unlikely the students knew anything about the man whom many affectionately called Father Ted.

Mike Gallo, the school’s assistant headmaster, waited inside the movie theater. Bus rosters in hand, he greeted students and directed them to their assigned showrooms. Months earlier, Gallo watched the film’s trailer. Then he watched an advanced copy on DVD. He admitted he didn’t know much about Hesburgh beforehand. After taking in the film, he believed it was a fit for the school.

“We’re a private school, but we’re a Catholic institution and our Catholic identity is important to us. I thought it would be good for us to see it together,” he said.

By the time Seton Hall Prep held this special screening in late May, Hesburgh had already gained some mainstream attention. It had been named a New York Times Critics’ Pick. Entertainment Weekly put it on the magazine’s must-see documentary list and the Los Angeles Times called the film “inspiring.” Some pop-culture stars offered support for Hesburgh on social media and success at the box office had already led to bookings in more than 50 cities across the country.

Standing in the theater that morning, though, Gallo felt nervous. Would the students understand it? Would it have an impact? Or would it fall flat for an audience born about 50 years after Hesburgh came to prominence at Notre Dame and across the nation?

A few hours later, Gallo had his answer. It started with the chatter on the buses back to school. The students spoke to each other about what they had seen. Back at Seton Hall Prep, the conversations on Hesburgh buzzed through the hallways.

Monsignor Michael Kelly, the 79-year-old school president and a revered Catholic leader in the state, suggested diocesan vocation directors show the film to young men considering the seminary because of how it captures the priesthood.

A few hours after the screening, a student sent a message to one of the filmmakers. “The film today was amazing. I loved it and I never thought I would be able to get so invested in a topic that I had no previous knowledge on.”

The following day, the school posted videos and photos of the field trip on its Facebook page. Parents responded. Hesburgh accomplished what little else can, generating lengthy conversations between teenagers and their parents.

“Thank you for taking my son to see this movie. He likely would never have seen it if it weren’t for the opportunity you provided. I can honestly say he spoke very highly of it, and it truly left an impact on him. Thanks again,” wrote one mom.

“Great story about an honorable man,” a dad wrote.

“AJ talked to me about this for at least an hour last night. Thanks so much to SHP for making these great opportunities happen for these young men,” wrote another mom.

Storytelling for the screen

Hesburgh died more than four years ago at age 97, but the story of his life, a servant leader who stood in the fire of controversy and provided solutions, continues to resonate today. Through the film, those who knew him have been shown the kind man whose faith led the way, whether on the global stage or walking across a northern Indiana campus. Those that didn’t know Hesburgh have been introduced to an unlikely figure, an ordinary man, a priest in the public square, who remained steadfast in his beliefs while battling for civil rights and building bridges between groups with seemingly irreconcilable differences.

Yet, mainstream success was far from a sure thing for Hesburgh. Outside of the Notre Dame community, Theodore Hesburgh lacks the name recognition to drive audiences to theaters. When people watch it on the big screen, though, they connect to the humanity on display, a person living life in service of a purpose bigger than oneself. And, as much as Hesburgh is packed with revelatory history, its themes of equal rights, kindness, and the relationship between those in power and the people they lead remain as timely as ever.

“Hesburgh is a fiercely inspiring documentary about a priest who set out to change a university but ended up changing the world,” wrote Eddie Fleisher as part of a review for the Cleveland International Film Festival.

In her review, Ann Hornaday, the lead film critic for the Washington Post, focused on the timeliness of Hesburgh’s story.

“This moving, illuminating slice of American life and social history serves as a stirring example that we should all do much better. And we can start right now,” she wrote.

When the filmmakers first rolled camera in 2016, they didn’t intend to make a timely film. As they moved deeper into the story, though, it became clear that there was a place in society, maybe even a yearning, for solution-oriented leadership that doesn’t alienate the opposition.

More than a year before filming began, a family friend suggested to director Patrick Creadon that Father Ted was worthy of a documentary subject. Creadon had just begun making “Catholics vs. Convicts,” an ESPN 30 for 30 film focused on the culture clash and classic 1988 football game between Notre Dame and the University of Miami.

Creadon had already made the critically acclaimed documentaries Wordplay, about the New York Times crossword puzzle, and I.O.U.S.A., about the national debt. What made “Catholics vs. Convicts” different than Creadon’s previous work is that this film was personal. The storied matchup had taken place during his senior year of college and was marked by controversy over a t-shirt his best friend made.

In making “Catholics vs. Convicts,” Creadon, a third-generation Domer, returned to his Notre Dame roots. As he revisited campus for the football story, Creadon had the idea of a possible Hesburgh documentary ruminating in his head.

He started work on the ESPN film a few months after his father had died. A few months before his father’s death, Hesburgh had passed away. Creadon connected the two. He vividly remembers his father continually telling the family about his 1960 graduation from Notre Dame, where a U.S. president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the future Pope Paul VI, Cardinal Giovanni Montini, were both present.

As “Catholics vs. Convicts” progressed, Creadon kept coming back to the idea of a film on Hesburgh. He decided to make it because, as he has said, he seeks out projects that fascinate and intimidate him. Hesburgh also fit what Creadon and his wife and producing partner Christine O’Malley look for in stories: ordinary people who do extraordinary things.

Creadon assembled a filmmaking team that included me, initially as a writer and later as a producer as well. Creadon never saw the film as a profit-making venture. It was made under the umbrella of a 501(c)(3) and therefore had benefactors instead of investors. All profit from the film will go to charities.

From the outset, Creadon wanted to be sure to tell a story for a wide audience. There was no intention to tell a “Notre Dame story” or a “Catholic story.” Of course, you wouldn’t avoid either of those topics when telling Hesburgh’s story, but the documentary would be made for a general audience. The storytelling would have to find a balance to reach an audience that would be a mix of people who knew Father Ted and those who didn’t know him at all.

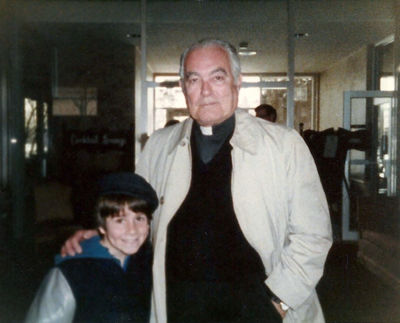

Jerry Barca, age 10, with Father Hesburgh.

Jerry Barca, age 10, with Father Hesburgh.

More than a dozen people on the production team have Notre Dame degrees, but nobody knew Hesburgh. Creadon, who graduated Notre Dame in 1989, spent his first two years at the school while Hesburgh finished his time as president. During that span, Creadon saw Hesburgh on campus, but didn’t interact with him. I met Hesburgh when I was 10 years old. It was at Notre Dame’s Morris Inn, where my father spotted him and told me to walk over and ask if he would take a picture with me. Hesburgh put his cap on my head before my dad snapped the photo. In 2012, for my book Unbeatable about the school’s 1988 national championship team, I recorded Hesburgh for 13 minutes on the topic of hiring football coaches at Notre Dame. Everyone on the filmmaking side knew what most people know about Hesburgh—the accolades. The Guinness World Record 150 honorary degrees. The 16 presidential appointments. But we didn’t know him nearly as well as we would need to in order to tell the story.

Getting to know Hesburgh: Researching a national story

Every member of the production team dug into different parts of the research. Archive producer Adam Lawrence scoured the country for material. He headed to the Chicago Public Library, the Chicago History Museum, the Vanderbilt Television News Archive, and the NBCUniversal Archives at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City. He reached out to the International Atomic Energy Agency for material on Hesburgh’s work with the Vienna-based group.

Lawrence found more than 1,000 letters that Hesburgh penned or that were sent to Father Ted. These included exchanges between Father Ted and Vice President and later President Richard Nixon as well correspondence between Hesburgh and Eppie Lederer, known by most as the ubiquitous advice-giving newspaper columnist Ann Landers.

At the UCLA Film & Television Archive, Lawrence found footage of Hesburgh and Martin Luther King Jr. standing arm-in-arm at the June 21, 1964, Illinois Rally for Civil Rights at Soldier Field in Chicago.

Lawrence looked into the archives at the Associated Press, ABC, Getty, Reuters, and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. In the Alabama state archives, he picked up footage of segregationist politician George Wallace blasting the work of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission. The repository held recordings of Hesburgh and the other founding members of the Civil Rights Commission presiding over public hearings. In one of these, an election commissioner pled the Fifth Amendment when he was asked to take the same literacy test he administered to prohibit African-Americans from voting.

At least a half-dozen members of the filmmaking team conducted research on the sixth floor of the Hesburgh Library, which houses the University Archives. Lawrence hunkered down there for days at a time. He scoured stacks of letters, yellowed newspaper clippings, old yearbooks, back issues of the school newspaper, The Observer, and the school magazine, Scholastic.

Lawrence’s most memorable experience came at NBCUniversal in New York. A guide led him to a windowless room carved into a cramped maze formed out of stacks of old film canisters. Lawrence searched through footage that had not been seen in decades. He chose some canisters and took a seat at a table whose top surface held a 1950s-style TV screen. His guide went to another area to load the film. Lawrence sat and watched NBC News broadcasts from yesteryear. When some of the footage made the cut for Hesburgh, O’Malley Creadon Productions became the first to digitize it, reviving it for the modern era.

Father Hesburgh and President Eisenhower in front of the Morris Inn, June 5, 1960. Courtesy of the Notre Dame Archives.

Father Hesburgh and President Eisenhower in front of the Morris Inn, June 5, 1960. Courtesy of the Notre Dame Archives.

The research also took Creadon back to his father’s 1960 graduation. Footage from that day, and the story of how Eisenhower and Montini came to campus for the occasion, made the film.

The presidential libraries of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Richard Nixon led to more material. Johnson’s handwritten journal noting Hesburgh’s “off record” attendance in the Oval Office provided a fitting accompaniment to Hesburgh’s telling of how the president used political power to push for a vote that turned the 1964 Civil Rights Act into reality.

One of the most significant findings from all our research came when a voice in the Oval Office could be heard talking about Hesburgh. Creadon and editor William Neal found the audio clips. They dialed their filmmaking teammates across the country. “You’ve got to hear this,” they said, and they played the audio into the phone. President Nixon badmouths Hesburgh’s efforts on behalf of equal rights. He can even be heard threatening to eliminate the Civil Rights Commission.

Researchers also combed through Hesburgh’s own writings and the books and articles written about him. Neal and editor Nick Andert, both co-writers on the project, used more than 20 hours of audio interviews to craft the voiceover narration.

All of the information culled from the research doesn’t end up on the screen, but it does inform the storytellers about the subject. In 1946, Hesburgh’s doctoral thesis called for expanding roles for the laity in the Catholic Church, foreshadowing some aspects of his relationship with the Vatican and the direction in which he led Notre Dame. The FBI released 436 pages of Hesburgh documents to the filmmakers and the CIA added 90 pages to that stack. Though they kick-started hours of explorations into what might be, nothing rose to the level of gaining entry into the film.

The crew conducted more than 60 on-camera interviews. They shot Ted Koppel of Nightline and former Senator Harris Wofford in Washington, D.C. Former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta sat for an interview in Monterey Bay, California. Creadon and company travelled to Cheyenne, Wyoming, to speak with former Senator Alan Simpson. Other interviews were shot in Los Angeles, Boston, Chicago, New Orleans, Alabama, and at Notre Dame.

To capture Hesburgh’s humanity and find the man away from the public eye, the filmmaking team interviewed people from his everyday life, folks who knew him differently than anyone else possibly could. This list included: his brother Jim; his niece Mary Flaherty; his bartender Patrick Murphy, a.k.a. Murf; his administrative assistant of nearly three decades Melanie Chapleau; his driver Marty Ogren and his late-in-life caregiver Amivi Gbologan.

All of this material had to be woven into a cohesive and compelling film. How does that happen? The best answer came when Creadon showed the documentary to Hesburgh’s brother priests at Holy Cross House, the retirement home where Father Ted lived out his final days.

After the film finished, one priest came up to Creadon and offered his thoughts. “Great job. Great film. Just a little bit too long,” he said, pausing before offering a suggestion. “Maybe cut five or seven minutes out, but great job.”

As Creadon took questions from the group, this same priest—who wanted a shorter film—kept raising his hand to ask why this or that story wasn’t included. By the time he finished, he had identified about a half-dozen other vignettes he wished were in the film. This is the impossibility with Hesburgh. He lived a vast life, which made it a difficult task to tell a 104-minute story.

Father Ted for the 21st century

The film made its world premiere at the American Film Institute’s documentary festival in Washington, D.C. The opening credits rolled at dinnertime on Father’s Day in 2018. Far from the Notre Dame campus, and at a time when other plans would have been understandable, people packed the theater. By the end of the final scene, sniffles and a few choked back sobs could be heard from the crowd. The audience had connected emotionally with Father Ted’s story.

Strong reactions continued throughout the festival run. Hesburgh won “Best Film” at the Waimea Ocean Film Festival in Waimea, Hawaii. At the Cleveland International Film Festival, Hesburgh won the documentary competition. After watching Hesburgh as part of the Napa Valley Film Festival, high school students from Napa Christian wondered how they hadn’t already learned about this man in history class. After a showing at the Heartland Film Festival in Indianapolis, a woman told Creadon, “I don’t have a question. I just want to thank you for restoring my faith in humanity.”

Hesburgh featured on the marquee of the Music Box Theatre in Chicago.

Hesburgh featured on the marquee of the Music Box Theatre in Chicago.

The next test came in the theatrical release. This would put Hesburgh alongside blockbuster Hollywood releases. It opened in Chicago and South Bend on the same weekend that Avengers: Endgame came to theaters. In South Bend, demand was so great for Hesburgh that the local AMC theater took a screen away from the superheroes and gave it to an overflow crowd there to see Hesburgh. During a late April snowstorm in Chicago, nearly 700 people piled into the Music Box Theatre. The live organist roused the crowd by playing the Notre Dame Victory March. The loudest ovation before the show came when it was announced that America’s favorite basketball-loving nun, 99-year-old Sister Jean Dolores Schmidt of Loyola University of Chicago, was in attendance.

As the film spread across the country, Chicago Fire star Miranda Rae Mayo took to Instagram and invited people to go to the theater with her. Award-winning journalist and former Today Show host Katie Couric posted about the film on Twitter and Instagram. “His moral authority, as well as his ability to cross partisan lines, is the perfect antidote for these troubled times!” Couric wrote.

Hesburgh played in Times Square, selling out multiple screenings. During opening week in Washington, D.C., people hoping to buy tickets the day of a showing were continually turned away because the room had been sold out well in advance.

The story of Father Ted stretched beyond Notre Dame and the Catholic community. Emails and social media posts described the inspiration people felt, the knowledge they gained, and the tears they shed.

“(I) walked out of the theater last night wiping tears from my eyes! Kudos to you and all of the people responsible for an incredibly rich historical story of a great individual. I learned so much from your film, even with growing up in the Vietnam and civil rights era when the world was turbulent, more so than now. Unfortunately, issues tend to repeat themselves blindly,” one non-Catholic wrote in an email.

Creadon felt Hesburgh’s impact as he made the film. Just before the world premiere, he made himself a reminder about one of his biggest takeaways from the story. On a red sheet of paper, he wrote the word “kindness.” He taped it to the wall next to his nightstand and he sees it each morning when he wakes up.

During question and answer sessions after screenings, someone typically raises a hand to offer something like this: “We need someone like him. Where is Father Ted in today’s world?”

Who is going to be that person to bridge the divide? Who can listen to others, even the ones we disagree with? Who can be that servant leader and problem solver?

That starts with each person. People can start in their neighborhoods and communities, at their jobs and in their homes. This is why Hesburgh has had the theatrical life it has had. Beyond the history, storytelling, and newsworthy reviews: when people watch, they connect with the film on a personal level. They leave the theater inspired both by what Hesburgh did and by what they can do with their own lives.

Jerry Barca is a producer and co-writer for Hesburgh and author of Unbeatable: Notre Dame’s 1988 Championship and the Last Great College Football Season (St. Martin’s Press, 2013).

This article appears in the fall 2019 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.