The middle decades of the 19th century were boom years for Catholic colleges in the United States. Historian of education Frederick Rudolph estimates that between 1850 and 1866 alone, some 55 Catholic colleges were established in the U.S. Among the founders of that era were a 28-year-old priest and seven brothers from a newly formed French religious community. Father Edward Sorin and his confreres from the Congregation of Holy Cross arrived in the United States in September 1841 and after several months in Vincennes, Indiana, were given 524 acres in northern Indiana near the south bend of the St. Joseph River. In November 1842, they arrived at the property’s snow-covered lakes and christened their as yet aspirational school L’Université de Notre Dame du Lac. Just ten days later, Sorin wrote to Father Basil Moreau, the founder of the Congregation, of his “firm conviction” that their new “undertaking cannot fail of success,” promising that it would soon be “greatly developed,” and predicting that “this college will be one of the most powerful means of doing good in this country” (41).

Despite his confidence, the odds were against Sorin and his confreres. Of those 55 Catholic colleges founded in the U.S. between 1850 and 1866, 25 had been abandoned by 1866. And yet nearly 180 years later, the University of Notre Dame stands as testimony to the success of Sorin’s striving. Notre Dame is today a top-twenty research university and an iconic institution in American Catholicism with over 130,000 living alumni, a legendary football team, and a nearly $14 billion dollar endowment.

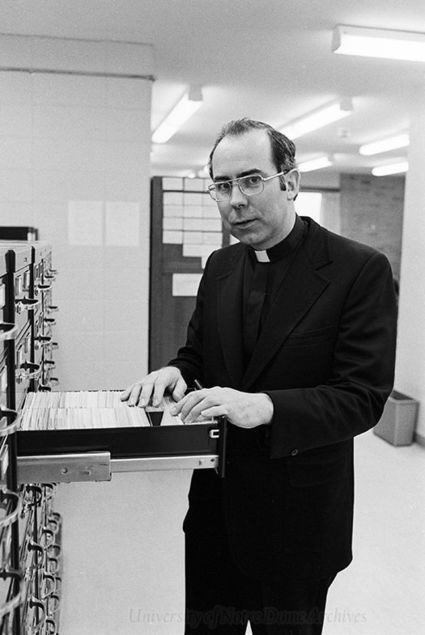

Few people are better equipped to tell the story of how Sorin and Notre Dame beat the odds than Father Thomas Blantz, C.S.C. Blantz arrived on campus as a high school freshman, earned his undergraduate degree in philosophy in 1957, and was ordained a Holy Cross priest in 1960. After obtaining a doctorate from Columbia University, he joined the faculty of Notre Dame’s history department in 1968 and was a beloved teacher for 45 years. In that time, he also held a number of administrative positions, serving as rector of Zahm Hall for three years, chair of the history department for six years, University archivist for nine years, and vice president for student affairs from 1970 to 1972. Blantz retired from teaching in 2013, shortly after his 80th birthday, and devoted himself to researching and writing a history of the University.

In his newly published 600-page tome, The University of Notre Dame: A History (Notre Dame Press, 2020), Blantz narrates the history of the University from the establishment of its founding religious order and the arrival of Father Sorin in Indiana to the inauguration of Father John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., as the University’s 17th president in 2005. The book’s 21 chapters are organized chronologically by University president, by decade, and by major moments in American history such as the Civil War, the Great Depression, and the two world wars.

Blantz now resides at Holy Cross House, the Congregation’s retirement home on the north shore of St. Joseph Lake, from where he graciously agreed to be interviewed by email amidst the restriction of visitors during the coronavirus pandemic. Our exchange was an opportunity for me to probe some of his broader perspective now that this major study is completed, and select quotes from our conversation are interspersed below.

A Holy Cross university

Blantz begins with a chapter on the French origins of the Congregation of Holy Cross, and the evolving relationship between the order and the University it came to found is a subtheme that runs throughout the text. As a fellow Notre Dame alumnus and Holy Cross priest, I was especially interested in how Blantz understood the relationship between the University and the Congregation that founded it.

Blessed Basil Anthony Moreau first brought the priests and brothers of Holy Cross together in 1837, in large part as a means of revivifying the Church in France after the destruction of the Revolution. Indeed, Blantz states that “it is not inaccurate to say that without the French Revolution of the 1790s there would be no University of Notre Dame in the 1840s” (2). Just four years after the Congregation’s founding, and a year after Moreau and Sorin were among the first of the community’s priests to make religious vows, Moreau accepted a request from Bishop Célestin de la Hailandière of Vincennes, Indiana, for priests and brothers to staff his young diocese. In 1841, Sorin left France on the overseas venture that would become, in Blantz’s estimation, “the congregation’s greatest success” (19).

The histories of the Congregation and of the University of Notre Dame were, therefore, virtually inseparable from the beginning. When Moreau resigned as superior general of the order, and his successor died shortly thereafter, Sorin was elected superior general of the Congregation in 1868. Until Sorin’s death in 1893, and again between 1906 and 1943, the international headquarters of the order moved to Notre Dame, and in 1872 when the Congregation’s general chapter was held at Notre Dame it was the first time that a general chapter of any religious congregation had been held in the New World (105).

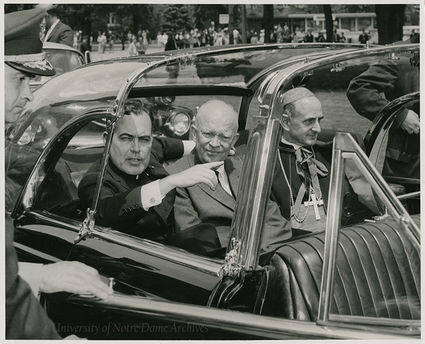

Throughout the University’s history, but especially in its earliest days, the Congregation provided priests as president, administrators, and teachers, including priest-scholars Father Charles O’Donnell, C.S.C., in literature; Father Julius Nieuwland, C.S.C., in science; Father Matthew Walsh, C.S.C., in history; and Father Michael Mathis, C.S.C., in liturgy (177). Until 1958, the priest-president of Notre Dame was also the religious superior of all the priests and brothers assigned to the campus. Because canon law limits the terms of religious superiors to six years, the presidency of the University was also limited to a six-year term (402). At the end of the first term of Father Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C., the roles of superior and president were separated, allowing Hesburgh to continue as president for another 29 years. Blantz believes this was an important change that allowed for Notre Dame’s long-term growth under Hesburgh’s leadership. It gave Hesburgh and his successors “greater freedom in planning for the future,” Blantz says, such as “what departments to build up now and which next, and which after that, or which buildings to put up now, and which ones after that.”

Theoretically, this also allows the Congregation and the University to prepare qualified Holy Cross priests to serve as president. “The Trustees do have to keep succession in mind and have someone available to succeed as president when the occasion demands,” Blantz says. He notes that the Trustees did this in the 1980s when they put Fathers Edward ‘Monk’ Malloy, C.S.C., E. William Beauchamp, C.S.C., David Tyson, C.S.C., and Ernest Bartell, C.S.C., “in important positions to prepare them for possible succession” of Father Hesburgh. There have also been, however, various moments when groups of students or faculty agitated for a change in the University bylaws to allow a lay person to serve as president rather than a Holy Cross priest (418, 479). “A layperson might be a more talented administrator,” Blantz admits, but he still believes that “a priest-president is better. Notre Dame’s Catholicity is one of its greatest attractions,” he says, “and nothing emphasizes ‘Catholic’ to the public and the world as much as a priest or religious as president and guiding spirit.”

While the histories of Holy Cross and the University have been deeply intertwined, and the Congregation was clearly instrumental in Notre Dame’s early development, Blantz doesn’t overtly address how Notre Dame may be different from other Catholic universities because it was founded by Holy Cross religious rather than, say, the Jesuits, as many Americans have long presumed. This uncertainty about the particularity of a Holy Cross university may lie less in Blantz’s analysis than in the order and the University’s self-understanding. Blantz records that in 1966, when the Congregation contemplated transferring the University’s governance to a lay board of trustees, Father Howard Kenna, C.S.C., the Holy Cross provincial at the time, stated “This is not primarily a Holy Cross institution: it is a Catholic institution” (431). And yet, as we shall see, Blantz’s research and teaching do suggest at least one important way in which Holy Cross may bring a unique charism to its mission in higher education and thus to the University of Notre Dame.

An American university

What is far more clear is that Notre Dame was always intended to be an American university. In the opening lines of his book, Blantz records that Sorin was grateful he “was not baptized under a French saint’s name” and that his given name, Edward, was free of “every vestige of nationality” (1). This was because “from the first day he stepped ashore, he wanted to be an American,” even kissing the ground when he landed in New York as “a sign of adoption” (1, 23). Sorin named an early campus building after George Washington, became an American citizen in 1850, soon after became postmaster and commissioner of roads for the area, and sent Holy Cross priests and sisters to serve as chaplains and nurses for the Union Army during the Civil War.

Even academically, Blantz says that “Sorin clearly wanted Notre Dame to be an American institution.” Sorin founded Notre Dame on the French six-year model, which included two years of high school and four years of college, but he patterned the curriculum and the methods of discipline after that of American universities, even writing to administrators at St. Louis University for advice on these matters. Under Father Auguste Lemonnier, C.S.C., in the 1870s and Father Andrew Morrissey, C.S.C., in the 1890s, Notre Dame added a third and then a fourth year of high school, further conforming Notre Dame to the American model of education. Father James Burns, C.S.C., eliminated the high school completely, bringing Notre Dame more in line with the development of other American colleges, and under Father Hesburgh, Blantz says that “Notre Dame patterned itself more and more after major American universities, with strong graduate programs and original scholarly research.”

Sorin’s patriotism and his desire for Notre Dame to be an American institution did not go unnoticed or unappreciated. In 1884, Sorin was invited to attend the Third Plenary Council of American bishops in Baltimore, and in 1888 when Sorin observed the golden jubilee of his ordination, Cardinal James Gibbons (America’s only cardinal), two other archbishops, and 12 bishops attended the festivities at Notre Dame. Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul lauded Sorin’s “sincere and thorough Americanism” in his jubilee Mass sermon, saying: “From the moment he landed on our shores he ceased to be a foreigner. At once he was an American, heart and soul” (2).

As Ireland’s sermon and the presence of so many dignitaries at Sorin’s jubilee made clear, Notre Dame quickly came to have an important place in American Catholic life. Blantz does not attempt to catalog all the many ways the University shaped American Catholicism or how changes in the American Church reshaped the University. In fact, Blantz says that he believes Notre Dame lived “almost independently of the rest of the American Church: it did what it saw as its mission to do; it cooperated with bishops and various Catholic organizations whenever asked; but, in general, had its eyes on its own educational mission and spent its efforts following it.”

Still, one does not have to read between the lines to recognize the important place Notre Dame has held in the development of American Catholicism. Throughout the book, Blantz records the numerous “firsts” the University achieved among U.S. Catholic universities, including establishing the nation’s first Catholic engineering program (109, 260), first Catholic agriculture school (211), and first Catholic law school (145), and opening Sorin College as the first Catholic college residence hall with private rooms (133). Even among all American universities, Blantz states that Notre Dame distinguished itself as the first campus with electricity (138) and the site of the first wireless message sent in the United States (161). No wonder, then, that when Bishop John Keane of Richmond, Virginia, was named the first rector of The Catholic University of America in 1886, he spent several weeks at Notre Dame gleaning advice from Sorin about establishing and developing a university (145). Sorin’s successors, too, played important roles in American and Catholic higher education. Father James Burns and Father William Cunningham, C.S.C., played influential roles in the founding and development of the National Catholic Educational Association, and Father Hesburgh was the first priest elected to the Harvard Board of Overseers and served as president of the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

But perhaps Notre Dame’s greatest single contribution to U.S. Catholicism was precisely that it helped prove Catholics could be truly American. And arguably nothing made that case more forcefully than the Notre Dame football team. Most institutional histories of major American universities likely wouldn’t contain as detailed a history of a college sports program as Blantz provides for Notre Dame football. But this is less a concession to the expectations of football-crazed alumni and fans and more an indication of just how central a role football played in Notre Dame’s success. “I think football has been very important in the history of Notre Dame,” Blantz told me, “especially under Knute Rockne.”

First and foremost, football’s importance can be understood financially. “In 1919, football made a profit for the University of $250,” Blantz says, and just a decade later “in 1929 the profit was $540,000. Rockne’s teams brought in over $2,000,000 in the 1920s,” funds that undeniably assisted in the construction of residence halls—including Howard, Morrissey, Lyons, Dillon, and Alumni Halls—as well as the South Dining Hall, and “perhaps aided faculty salaries.” Even today, football “continues to help balance the University budget.” But more than that, Blantz argues that “football helped give Notre Dame national fame,” which made the University “more attractive to prospective students, faculty, and benefactors.” It also helped inspire generations of American Catholics, still judged as less than fully American by the nation’s Protestant majority, to see themselves as equal to the blueblood schools Notre Dame vanquished on the gridiron.

A Catholic university

While Sorin undeniably strove to make Notre Dame an American university, he along with his contemporaries and most of his successors would absolutely have taken for granted the fact that Notre Dame was a Catholic university—and the means by which it would remain so. Blantz details devotional life on campus especially under prefect of religion Father John O’Hara, C.S.C., later president of the University and then cardinal archbishop of Philadelphia. O’Hara’s religious program, which included a daily bulletin providing exhortations to virtue, listing prayer requests, and detailing the number of Communions received on campus each day “was the envy and model of many Catholic institutions across the country” (284).

By the 1960s, however, the mission and nature of a Catholic university, like so much else in the Church and in American society, was ripe for reevaluation. Blantz narrates the significant changes to American Catholic higher education that occurred in this era not only in curriculum, discipline, and student life, but in university governance and in schools’ self-understanding of mission as well. In January 1967, on the initiative of Father Hesburgh as the University’s president and with approval from Roman authorities, an extraordinary provincial chapter voted to approve the transfer of control over Notre Dame from the Congregation of Holy Cross to a predominantly lay board of trustees (431).

Later that same year, Hesburgh convened a meeting of presidents of Catholic universities at Notre Dame’s property in Land O’Lakes, Wisconsin. Nine university presidents, two bishops, and several leaders of religious orders collaborated on a statement outlining the mission and character of a Catholic university. Most controversially, the statement insisted on the “true autonomy” of the university “in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself” (432). The Land O’Lakes Statement has come to be portrayed by some as a declaration of independence from the Church that is at the root of a subsequent decline in the Catholic character of Catholic universities in the United States.

Blantz acknowledges that the statement “might have been worded a little too strongly” and that much about what made a university Catholic “was presumed or left unsaid.” But he isn’t negative about the statement, highlighting that the authors would have understood that Notre Dame would never have complete autonomy from the hierarchy since provincials could reassign, and the Vatican could laicize, any priest-president if they thought it necessary. Even more importantly, Blantz notes that Father Hesburgh understandably wanted to avoid non-academic interference by ecclesial authorities. In 1943, at the request of the papal nuncio to the United States, University president Father Hugh O’Donnell, C.S.C., had required Professor Francis McMahon to have his public speeches pre-approved by University officials because the Vatican felt he had been too critical of Francisco Franco of Spain and too favorable toward Communist Russia (332). And in 1954, the Vatican had pressed Father Hesburgh to destroy copies of a book published by the University of Notre Dame Press containing an article by Jesuit Father John Courtney Murray on church-state relations. Murray had agreed to remain silent on the issue at his superior’s insistence, but Hesburgh refused to destroy the already published collection (388). At Land O’Lakes, Hesburgh was clearly intent on avoiding the reoccurrence of such controversies.

In the years since Land O’Lakes, concern about Notre Dame’s Catholic character has often centered on the number of Catholics on the faculty. A “Committee on University Priorities” in 1972, a “Priorities and Commitments for Excellence” statement in 1982, and the 1993 “Colloquy for 2000” all argued that “the Catholic identity of the University depends upon and is nurtured by the continuing presence of a predominant number of Catholic intellectuals” (549) and that “if Notre Dame is not more successful in attracting Catholics, it will cease to be a Catholic university in a generation or two” (489). In the academic year 1993–1994, however, only 30 percent of Notre Dame’s newly hired faculty were Catholics, an all-time low. Blantz assesses that Notre Dame has “retained its fundamental Catholic character” (602) which he says is maintained not only through faculty, but “through ministry in the residence halls, through the campus-wide work of Campus Ministry, through the theology requirement in the curriculum” and in myriad other ways. But he agrees that “the faculty needs to be predominantly Catholic also” and says that the challenge is in selecting the very best scholars while also recruiting a sufficient number of Catholic academics.

Sources of excellence

Of course, Blantz isn’t the first Holy Cross priest or Notre Dame professor to tackle the history of the University. Blantz says he was “privileged” to rely on Notre Dame, One Hundred Years (University Press, 1943) by Father Arthur J. Hope, C.S.C., especially for information on University Presidents John W. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., Andrew Morrissey, C.S.C., and Matthew Walsh, C.S.C. Professor Thomas J. Schlereth’s The University of Notre Dame: A Portrait of Its History and Campus (Notre Dame Press, 1976) “was excellent in the cultural area and on the Main Building and Sacred Heart Basilica,” Blantz says. And Professor Robert E. Burns’ Being Catholic, Being American: The Notre Dame Story (Notre Dame Press, 1999) provided details of a disgruntled former professor, Charles Veneziani, who in the early 1900s “published two broadsides against the University” and of the debates between two Notre Dame professors, Father John A. O’Brien and Francis McMahon, over American foreign policy at the start of World War II (164).

From his nine-year tenure as University archivist, Blantz was also able to rely on his intimate knowledge of the correspondence, student records, minutes of meetings, financial ledgers, press releases, and campus publications contained in the University Archives. Established by Professor James Farnham Edwards in 1872, the archives “have collected excellent resources for Notre Dame history and the history of American Catholicism” and, Blantz says, “is today one of the finest collections of such material anywhere in the world.” Blantz acknowledges relying “rather heavily on student publications”—including Scholastic, Observer, Notre Dame Report, Notre Dame Magazine, and Alumnus—especially in his later chapters. While noting that student journalists are “still young and inexperienced,” and that they write “from a student’s point of view,” Blantz says he found student publications to be “very helpful overall” and an especially good source for insight into student life, campus lectures, events, and visitors.

But campus newspapers and magazines weren’t the only student-produced sources Blantz employed in his research. Having taught numerous senior history seminars, including on the history of Notre Dame, Blantz was greatly influenced by his own undergraduate students, to whom he has dedicated his book. “The comments and questions from students in the classroom,” Blantz says “helped me to rethink or clarify my positions and gave me new insights into the topics we were discussing.” More than that, research and writing undertaken by his seminar students—including papers on “The History of Notre Dame Track and Field,” “The Collegiate Jazz Festival,” “The Monogram Club,” and “The History of the Glee Club”—provided lessons on aspects of the University’s history even Blantz was unfamiliar with, and he says, “their footnotes guided me directly to the sources I needed to consult.”

As an undergraduate history major, I myself took a senior seminar with Father Blantz, and my path to the twin vocations of priest and historian owes a great deal to his influence and example. I recall that when I wrote my seminar paper on Archbishop Joseph Rummel and the desegregation of New Orleans’ Catholic schools, it was the first time a professor had suggested I should pursue the publication of my research and writing. It was clear that Father Blantz saw those of us in his class not only as his students but as his collaborators, along with his faculty colleagues, in the search for truth. Perhaps that collaboration is the crucial hallmark of the Holy Cross influence on the University it founded and the wellspring of the oft-lauded “Notre Dame Family.” As the Constitutions of the Congregation of Holy Cross state, “in every work of our mission, we find that we ourselves stand to learn much from those whom we are called to teach.” Reflecting on his career at Notre Dame, Blantz echoed those same Constitutions. “I have learned much from students over the years,” he told me, “Students’ friendships and example in the residence halls . . . the good lives they were leading, the ideals they had, their devotion to prayer and the sacraments, and their lifelong friendships have been inspirations for me.”

I was disappointed that protocols enacted to stem the tide of the COVID-19 pandemic kept me from visiting with Father Blantz in person. But I was thereby inspired to ask him how this most challenging academic year compared with other moments of crisis faced by the University—especially the 1918 Spanish Flu, which Father Cavanaugh said “was almost the death of all human joy”—and how Notre Dame had been able to beat the odds from its earliest days until now. Although Notre Dame saw two hundred cases of flu and nine student deaths during the 1918 pandemic, Blantz ranked the fire of 1879 as the greatest threat to the University’s survival. The Civil War and World War II also were grave threats to the University’s enrollment and staffing. But in every instance, Blantz credits strong leadership, the contributions of Holy Cross priests, brothers, and sisters, and “the dedication of so many lay faculty members” as well as “the grace of God and the intercession of the Blessed Mother” with bringing Our Lady’s University through its first 180 years. Blantz’s latest publication has now become the definitive chronicle of that history.

Rev. Stephen M. Koeth, C.S.C., is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center.

This article appears in the spring 2021 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.