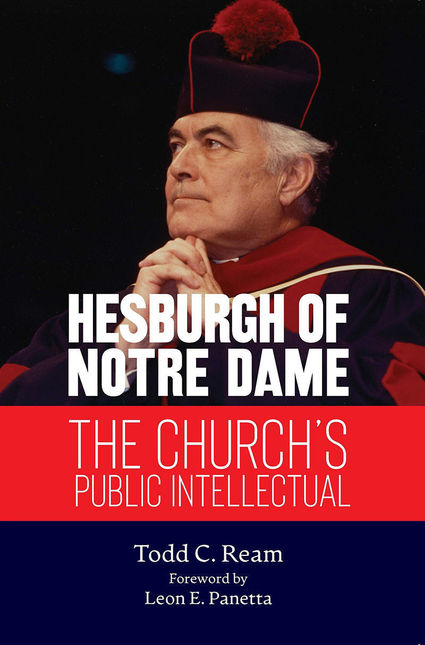

Todd C. Ream serves on the higher education and honors faculties at Taylor University, as a fellow with the Lumen Research Institute, and as the publisher for Christian Scholar’s Review. He is the author and editor of a number of books and contributes to a wide variety of publications including Christianity Today, First Things, Inside Higher Ed, Modern Theology, and New Blackfriars. In 2017, he won a Theodore M. Hesburgh Research Travel Grant from the Cushwa Center, and the resulting research informed his latest book, Hesburgh of Notre Dame: The Church’s Public Intellectual (Paulist, 2021). Cushwa Center postdoctoral research associate Philip Byers recently corresponded with Ream about the book.

Philip Byers: You have spent much of your career researching and writing about Christian higher education, often at a conceptual level—for example, how Christianity interacts with scholarship, interdisciplinarity, the formation of moral identity, and campus community life. What inspired you to focus now on the particular life and career of Father Ted Hesburgh?

Todd Ream: While in graduate school, I wrote a paper about Father Hesburgh, so his life and legacy have been in the back of my mind for at least 25 years. That interest then formally resurfaced at a point in time when I believed my research agenda concerning Christian higher education had run its course for at least the foreseeable future.

An even larger part of that decision likely had to do with Father Hesburgh’s passing in 2015 and the privilege I had of attending most of the related events on campus. For example, I remember walking behind the funeral procession (on what was a brutally cold day even for South Bend) from the Basilica of the Sacred Heart to the Holy Cross Community Cemetery. Thousands of students who were not even born when Father Hesburgh retired lined the road in silence, paying their respects. The reverent looks on their faces, some of them in tears, confirmed that no one compelled them to wear their Sunday best and face the cold on that day. They somehow knew Father Hesburgh gave his life to their university, Church, and nation in ways meriting their presence. That moment, perhaps more than any other, confirmed that his story was worth telling.

PB: At the heart of this book lies a premise about the significance of vocation: Previous analyses, you contend, “failed to come to terms with what animated Hesburgh,” namely his calling to be a priest. You quote him drawing upon Thomas Aquinas to argue that a priest “is essentially a mediator because he joins the greatest of all separated entities: the all-holy God and sinful humanity.” How did Father Hesburgh’s conception of his calling “to exert a mediating influence in the contemporary society” guide his work?

TR: While Father Hesburgh was pulled in many different directions as a university president and by the myriad appointments he accepted, his understanding of his calling is ever-present and definitive. He formally began to articulate that conception as far back as his dissertation and first book, The Theology of Catholic Action, but it surfaces time after time in subsequent writings and speeches.

Perhaps one place to see that understanding at work is when he felt least qualified. For example, when representatives of the Eisenhower White House asked him to serve on the National Science Board, he initially responded that his expertise resided elsewhere and thus questioned how he could be of service to such a group. He eventually came to understand that his calling, in that case, was to mediate between the physical or temporal realities of science and the metaphysical or eternal realities of theology. The two were not independent of one another. Instead, human flourishing demanded the two be drawn into proper dialogue. At that time and in that way, he viewed himself as someone whom God called to mediate between the two.

Perhaps another place to see that understanding at work is when it proved controversial. For example, Father Hesburgh’s critics often refer to his record on abortion as being inconsistent and his service on the board of the Rockefeller Foundation as a considerable example of that inconsistency. Although a relatively small percentage of its budget, Rockefeller Foundation funding supported entities that, in turn, supported abortion providers. While Hesburgh made his opposition to the practice of abortion clear to members of the board, he believed it was better for him to be present at that table than to withdraw. Some may argue that doing so made him complicit, and that argument may merit debate. However, Father Hesburgh believed his calling as a mediator compelled him to be present and to share his beliefs even if the board occasionally made decisions to the contrary.

PB: As suggested by the book’s subtitle, one other key theme involves Father Hesburgh’s role as a “public intellectual.” How do you define the work of a public intellectual, and what did Father Hesburgh believe regarding the public-facing responsibilities of university administrators?

TR: I think the most concise definition is one Michael Desch offered at the beginning of his edited volume Public Intellectuals in the Global Arena—public intellectuals are “persons who exert a large influence in the contemporary society through their thought, writing, or speaking.”

Hesburgh believed administrators—and university presidents in particular—were called to exercise mediatorial forms of influence. He also believed faculty members were called to do so. As a priest, he was called to do so first and foremost by presiding over the sacraments. However, he believed priests and laypersons alike were called to exert mediatorial forms of influence and to do so in a number of other ways. Everyone who accepted Christ’s grace had a role to play, and college educators have expertise that can be of service to the Church and society.

When thinking about administrators and, in particular, university presidents, Hesburgh believed they also played symbolic roles in relation to members of their respective university communities. As a result, he believed the service he provided, for example, to the National Science Board and Rockefeller Foundation signaled to Notre Dame administrators, faculty, and students that they were called to offer comparable forms of service in their own unique ways.

PB: In the book’s acknowledgments, you make a point that will warm the heart of any practicing historian: Father Hesburgh’s published writings are rich but not sufficient as a gauge of his influence. What did research in the Notre Dame Archives and attention to Father Hesburgh’s various speeches reveal about the evolution of his thought?

TR: I cannot speak in comprehensive terms yet about Father Hesburgh’s thought; the Notre Dame Archives alone contain 518 linear feet of material. What I believe I can offer at this point is that Father Hesburgh’s theological understanding of a public intellectual as a mediator did not change over the course of his life.

What one finds in the archival material, for example, is how Father Hesburgh applied that understanding to complex matters such as ecumenical relations, immigration reform, civil and human rights, and health care—to name only four. What I then believe proves impressive is the core of his calling does not change. What changes is how he applies that calling and, given the diversity and complexity of those matters, the incredible range and nuance of how he exercised it.

In terms of gauging Father Hesburgh’s influence, one then needs to turn to various other sources for assistance. Newspaper stories and op-eds concerning Father Hesburgh are of great value as are interviews with his contemporaries in academe, the Church, and the U.S. government. Together, those sources offer critical indications of the extent of Father Hesburgh’s influence.

PB: The project has won commendation from a truly wide range of figures: not only leading Catholics, but also Protestant theologians and administrators and even persons with no tie to Christian higher education, such as former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta. What factors explain Father Hesburgh’s broad appeal?

TR: Like the students who lined the road between the Basilica and the cemetery during Father Hesburgh’s funeral procession, many people recognize Father Hesburgh offered higher education, the Church, and his nation a life of service worthy of serious consideration. Those perceptions exist within and beyond the Church just as they exist within and beyond the United States.

Interestingly, some of Father Hesburgh’s critics are also his most devoted admirers. For example, I had the privilege of talking about Father Hesburgh with former Harvard president Derek Bok. While Bok admired many of the commitments that defined Hesburgh’s life (and was the commencement speaker at the last commencement over which Hesburgh presided as president), Bok was also quite clear in his belief that Father Hesburgh did not do enough to reform college athletics when serving as the founding co-chair (along with the University of North Carolina’s Bill Friday) of the Knight Commission.

I fear in some ways, however, those sensibilities are changing within the Church and in society. Unlike Bok, too many of us reserve respect for individuals who represent the ideological purity we quietly know we do not embody. Part of what Father Hesburgh represents is the need to grapple with the legacies people offer in their full complexity. In many ways, the breadth and depth of his efforts mean no one who is truly honest will agree or disagree with all of the decisions Father Hesburgh made.

In the end, I hope Father Hesburgh’s enduring appeal will be as a finite human being who understood that his mediatorial calling compelled him to address the greatest challenges of his day even if we disagree with some of the decisions he made.

PB: While it’s clear that your own interest is far from sated, Father Hesburgh’s rich life could support almost limitless inquiry. Specifically, what advice would you offer to other scholars who hope to research Father Hesburgh, and generally, what can you share with anyone intending to capture broad insights from a particular life?

TR: In many ways, I believe Father Hesburgh’s life is a fascinating window into the complexities of the 20th century. As a result, the range of ways his life offers insights into the Church and American society during those years is greater than I can count. I thus would encourage almost anyone doing work during that period of time to ask what, if anything, Hesburgh’s life has to offer.

I would, however, caution anyone to consider making sure they begin by coming to terms with how Hesburgh understood himself. In my estimation, the place to begin is with how Father Hesburgh understood the mediatorial influence he was called to exercise.

As a result, one cannot understand the service Father Hesburgh offered as a member of the Civil Rights Commission, for example, apart from how he understood theological concepts such as what it means to be human. The record of what occurred, what was accomplished, etc., while important, only makes up part of the story. How Hesburgh understood his calling when serving in such a capacity is just as critical.

PB: Now that Hesburgh of Notre Dame has reached the public, what is the next step in your long-term Hesburgh project?

TR: When I started this project in late 2015, my immediate thought was to write a comprehensive biography of Father Hesburgh’s life. That is a project I hope to begin in early 2022, but back in 2015 I quickly realized I had a fair amount of related work I needed to do first.

This book, for example, represents where I learned I needed to start—by coming to terms with what theologically animated Father Hesburgh. I think charity is one of the most important virtues that scholars can exercise. In order to tell someone’s life story (or even a facet of it), scholars must understand their subjects (as much as our finitude will allow) as they understood themselves. I believe that only after doing so can we rightfully come to terms with their successes and failings. Perhaps a more apt title for this first book then is Hesburgh of Notre Dame: A Theological Primer.

I then moved to thinking through how to organize the various ways Father Hesburgh invested his time and energy. That effort is represented in a book scheduled for release in August 2021 titled Hesburgh of Notre Dame: An Introduction to His Life and Work. In many ways it represents my attempt to establish footholds or ways of placing Father Hesburgh’s life and legacy into manageable yet interrelated categories.

Once those footholds were established, I realized I had little chance of becoming an expert in all of the ways Father Hesburgh invested his time and energy. Along with Boston College’s Michael James, I am presently editing a volume of essays titled Hesburgh of Notre Dame: Assessments of a Legacy. That volume is organized along the lines of those footholds and asks, for example, a noted scholar of civil and human rights to assess the historical significance of Hesburgh’s respective efforts.

Along with Notre Dame’s Father Gerard J. Olinger and the University of Portland’s Hannah Pick, I am also presently editing a volume titled “Come, Holy Spirit”: The Selected Spiritual Writings of Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. Explicitly, that volume is designed to shed further light on how Father Hesburgh theologically understood and expressed himself. Implicitly, that volume is designed to do so in ways that are of formative spiritual benefit for religious and laypersons alike.

To bring the answer back around to the point of the question, only after completing those volumes do I believe I will conceptually and logistically be ready to grapple with Father Hesburgh’s life through an effort such as a comprehensive biography.

Philip Byers is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism.