Candice Shy Hooper

Candice Shy Hooper

Candice Shy Hooper is an independent scholar working on a book project titled Lincoln & His Generals’ Wives: How Four Women Influenced the Course of the Civil War—for Better and for Worse. She is a 2013 Research Travel Grant recipient and was on campus earlier this fall to conduct research. Her manuscript is currently under consideration by a university press.

1. What initially got you interested in this topic?

My interest was sparked in 2008, when I learned that, early in the Civil War, the wife of General William Tecumseh Sherman had traveled from Lancaster, Ohio, to Washington, D.C., to ask President Lincoln to support her husband, who had been labeled “Insane” by a host of national newspapers. I had known from earlier reading that General John Fremont’s wife had made a similar mission to Washington to ask Lincoln to help her husband, so I began to wonder whether there were more tales in this vein. After preliminary research, I decided to focus on the wives of four of Lincoln’s generals—Fremont, Sherman, George McClellan, and Ulysses Grant—and how they helped or hurt their husband’s careers.

2. You made extensive use of Notre Dame Archives’ digitized materials before you arrived on campus. What did they allow you to accomplish?

I sing the praises of the Notre Dame Archives digitized collection wherever I go. When I began my project, I didn’t know how much I could find out about each of the wives I was studying—or how much research I could do at all, because I travel so much. When I turned to the Shermans, I hit the jackpot. Not only does Notre Dame have Ellen’s original letters digitized, but the letters are also available in transcribed form. For more than five years, as long as I had an Internet connection, I was able to continue my research no matter where I was.

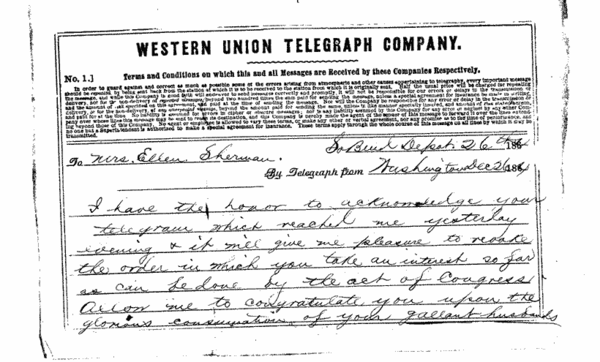

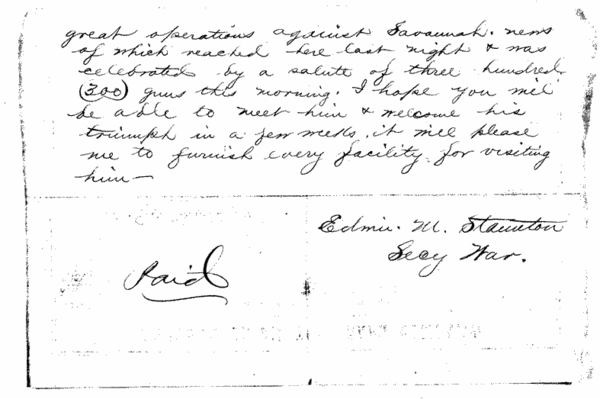

The William T. Sherman Family Papers Collection comprises one of the most extensive and intimate views of the Civil War experience: more than 400 letters each from Ellen and William T. Sherman are in the collection. Of the four couples I studied, theirs is the only complete collection of letters; fewer than a dozen total letters survive that were written by the other three wives.

Since the collection also includes letters from and to Ellen’s father and mother and sisters and brothers and children, and some of her husband’s family, too, it was a particularly rich research experience for me.

2. What collections did you come to examine in person?

Ellen Ewing Sherman was a devout Catholic—one of the most prominent laywomen in the United States during the 19th century—and because of her early devotion to Notre Dame, her children left their parents’ papers and their own to the University. I came to the Notre Dame Archives to look at items in the William T. Sherman Family Papers Collection that have not been digitized. Primarily, I wanted to see the physical objects that the family had entrusted to the Archives, in the hopes of finding things I could use for illustrations in my book. There are relatively few such items because so much is digitized, but I wanted to be sure I hadn’t missed anything of possible importance. The Sherman Collection is astonishingly rich since it encompasses much of the Ewing Family Collection as well. The Ewings and the Shermans were among the most prominent families in Ohio, and indeed in the United States, throughout the 19th century in political, military, and social spheres.

3. Did you discover any other helpful collections?

One day when I was browsing the Archives website before my visit I stumbled upon a collection of letters between priests, bishops, and archbishops during that same time period. Called The Archdiocese of Cincinnati Collection, it is an amazing window into what was then the West, now the Midwest. The focus of the collection is on the establishment of churches in areas where there were few Catholics. But in the course of their close attention to their small flocks, the priests, bishops, and archbishops reported on economic booms and busts, outbreaks of disease, establishment of newspapers and cultural venues, and political activity before, during, and after the Civil War. I believe this is a treasure trove for anyone who wants to know what was going on in the Midwest in the 19th century, whether or not their focus is on Catholicism.

I barely scratched the surface of the Cincinnati Collection, but I found valuable information in it for my project. For example, no historian had been able to put a name to Ellen’s lifelong illness, but in the Cincinnati Collection I found a letter from 1845, in which her priest reported to his bishop that “Thomas Ewing’s daughter continues to suffer from scrofula,” a particularly painful and often disfiguring disease.

Because I found the Cincinnati Collection through a chance computer search for the name of Ellen Ewing Sherman’s bishop, I really didn’t understand what it was until I arrived at the Archives. Kevin Cawley, archivist extraordinaire, took the time to explain the collection and its genesis to me. He and his staff were incredibly helpful in guiding me through the collections and in telling me about items that were held off-site. While I might have felt satisfied if I’d received the same information via email or phone calls, I now know that I would not have the same understanding of the materials that I got by being there and working with the staff.

5. Were there other highlights of your time here?

In addition to researching in the Archives with expert archivists, I was looking forward to the experience of being at Notre Dame for several reasons. First, because it was where Ellen Sherman spent much time, and where their young son Charley, who was born and who died during the war, was buried. I wanted to soak up some of that history. It was marvelous to happen upon the Rosary Crown in the Golden Dome, and to see Ellen’s name listed as one of its prominent financiers.

Second, I was anxious to meet Kathleen Cummings, director of the Cushwa Center and one of the foremost authorities on women and the Church in America. She and I had communicated before my visit about Ellen Sherman, but she generously spent time with me during my visit, discussing my topic and encouraging me.

And finally, I had the great pleasure to meet another professor during my visit. I had long been intrigued by a comment that Sherman made to his wife in a letter, comparing himself to Shakespeare’s character Coriolanus. Just before I arrived at Notre Dame, I learned that one of the world’s leading Shakespeare scholars, Peter Holland, holds the McMeel Chair in Shakespeare at Notre Dame. Dr. Holland generously spent time with me, exploring similarities between Sherman and Coriolanus.

Opportunities to spend time with such leaders in their fields are rare. I valued the chance to learn from Dr. Holland and Dr. Cummings, which never would have happened had I not received the Cushwa travel grant.