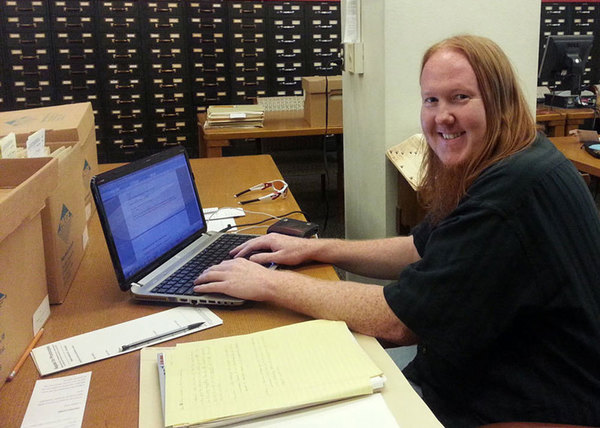

Henry Maar, a PhD candidate in history at the University of California Santa Barbara, is one of the Cushwa Center’s research travel grant recipients for 2013. We caught up with him earlier this summer during his week at the Notre Dame Archives.

What’s the topic of your dissertation?

My dissertation explores the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign of the 1980s, its influence on American society, and, subsequently, as I argue, the atomic diplomacy of the Reagan administration. The Freeze campaign was a social movement that emerged in the early 1980s as a reaction to the escalating arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. It pushed a very simple message as a solution to the arms race: a bilateral freeze on the testing, production, and deployment of nuclear weapons.

By examining the Freeze campaign, I thought I could begin to understand the Cold War not just from an official or diplomatic standpoint, but also from the standpoint of everyday citizens.

What materials were you looking at while you were here?

I looked at the papers of Pax Christi and those of [Detroit Auxiliary] Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, specifically with regard to “The Challenge of Peace,” the 1983 pastoral letter on war and peace.

There were a number of documents that helped me rethink portions of my work. For instance, prior to my research here, I was not aware of how influential Pax Christi was in lobbying bishops to sign the pastoral letter. And within Gumbleton’s papers, I found handwritten notes about a meeting he had with members of the Reagan administration.

The material I examined at Notre Dame will go into a chapter I’m writing on the Catholic Church and the pastoral letter on war and peace, and how that fits in with the Reagan administration’s pursuit of the arms race and the challenge presented by the Nuclear Freeze movement. But I’ve found so much material on this one aspect that I’m considering writing a separate article just on the Catholic angle alone, or taking parts of this chapter and expanding on it for a larger study of Catholics and the Cold War.

How did you connect with the Cushwa Center?

My training and background are grounded in diplomatic and Cold War history, and I came to the Cushwa Center through the advice of my advisor, Nelson Lichtenstein, who had mentioned travel grants that would help me get to some of the archives I wanted to visit.

Interestingly, there’s a growing community of scholars concerned with the study of religion and foreign policy, and I’m sure many of those scholars would find interest in the archives at Notre Dame.

How does the “Catholic angle” help you understand your topic in a new way?

The Catholic angle really highlights the complexities of both the Nuclear Freeze campaign and the way in which arms control was thought about and debated. If the movement had been limited to just ’60s activists or liberal Democrats, the Reagan White House wouldn’t have taken it as seriously. The Catholic bishops brought a level of respect to the movement, and they occupy the space between the Freeze movement, which they gave moral backing to, and the Reagan White House, which viewed Catholic voters as crucial to their re-election hopes in 1984.

The Catholic angle really highlights the complexities of both the Nuclear Freeze campaign and the way in which arms control was thought about and debated. If the movement had been limited to just ’60s activists or liberal Democrats, the Reagan White House wouldn’t have taken it as seriously. The Catholic bishops brought a level of respect to the movement, and they occupy the space between the Freeze movement, which they gave moral backing to, and the Reagan White House, which viewed Catholic voters as crucial to their re-election hopes in 1984.

I’ve also been able to get to the voices of lay Catholics through the thousands of letters written to Bishop Gumbleton and Joseph Cardinal Bernardin (in the Archdiocese of Chicago’s Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives) by people of all walks of life. Many wrote how the pastoral letter renewed their faith. But not everyone was pleased—in fact, many wrote to the bishops with insulting remarks. I found one letter to Bernardin calling him a “quisling,” and another to Gumbleton calling him “both wrong and phony.” Other letters critiqued the pastoral letter for not telling Catholics to “pray more” or for ignoring the message of the Lady of Fatima. Still others thought it was sympathetic toward the “totalitarian Soviets” who were “waiting for us to disarm so they can strike.” Many of the letters also expressed concern the morality of a nuclear freeze was being placed above abortion.

What do the collections here provide that you don’t see elsewhere in your research?

One of the key differences between the files in Notre Dame’s archives and the files in the Reagan Library, for instance, is how the issue of a nuclear freeze was interpreted. For the Reagan administration, it’s all political. It’s about elections, public opinion, and the politics of national security. For the bishops—and Catholics more generally—it’s about more than that. It’s about morality and the definition of pro-life. It’s about theology and attempting to understand how just war theory fits into the nuclear era. So you have people looking at the same problem—the arms race—from very different vantage points.