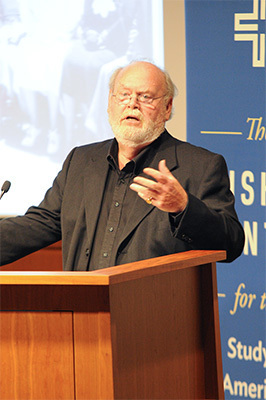

Thomas P. Lynch

Thomas P. Lynch

Thomas P. Lynch, a poet and funeral director with roots in Ireland and Michigan, combined reflections on life and death with tributes to two recently deceased Irish poets when he spoke at Notre Dame on September 9, 2016. The occasion was the Cushwa Center’s annual Hibernian Lecture, focused this year on the work of Seamus Heaney and Dennis O’Driscoll, both of whom Lynch considered from his perspective as an Irish-American writer who deals professionally with death and dying. He honored the two masters of multiple genres, who died in 2013 and 2012, respectively, by recalling their inspiration for his own writing.

Lynch echoed their stories about solidarity in difficult journeys, relevant to the experiences of Irish immigrant families in the United States, through a lecture and poetry reading titled “Shoulder and Shovelwork: Dead Poets and Eschatologies.” He explained the title’s inspiration in terms of Seamus Heaney’s promise to work in words with the same diligence he had observed in his father’s work with the soil.

Lynch himself has written about such things as the dignity and difficulties of immigrants’ travels. September’s lecture, however, drew more on his work as a funeral director called to honor the joys and brokenness revealed when a life ends. He was a National Book Award finalist in 1987 for his first book of poems about living and dying, Skating with Heather Grace. One of his books of essays, The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade, inspired a 2007 “Frontline” documentary of the same name. The PBS production won an Emmy award for best art and culture documentary.

In the audience were members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) and Ladies AOH.

In the audience were members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) and Ladies AOH.

Recalling the thrill of seeing Heaney speak at Emory University, Lynch said that Heaney “had been the most amplified and ever-present voice of my generation of poets.” Thanks partly to a Catholic upbringing in Ireland, Heaney’s words always yielded “a rich trove of metaphoric treasure,” Lynch said. He cited the poem “Funeral Rites,” in which Heaney was coping with death amid the Irish Troubles, but nevertheless “shouldered a kind of manhood” by preserving ritual and carrying the coffins of family members and others.

Lynch also looked back to the Christmas Eve death of Dennis O’Driscoll, with whom he had a 25-year friendship. O’Driscoll was “Ireland’s most bookish man,” one of the country’s “undercelebrated” poets, and the best biographer of Heaney, Lynch said. He decided to travel to O’Driscoll’s funeral partly because he had read that Heaney once journeyed a long way to the funeral of a writer who had influenced him.

“The witness of Dennis’ burial, the witness of Seamus’s burial, drew in me a catch in the breath that I still have not let go of,” Lynch said.

Lynch’s career as a funeral director has allowed him the privilege of regularly being present with mourners as they gather around their deceased. These occasions often elicit the eloquent remarks that “priests and pastors and rabbis and imams, poets and poohbahs and perfect strangers, bring to these horizontal mysteries—at bedside, at box-side, at graveside,” Lynch said. He added: “I’ve been graced, I’d have to say, by my witness of the lifting and burying and carrying that we all do for one another.”

“The language of shoulders and shovels and aching backs” is what Heaney “learned as a farm boy in Derry,” Lynch said. The Irish more broadly, said Lynch, still carry their dead to the grave themselves, and close it themselves, as the minimum honor due. The funeral director from Milford, Michigan, warned that American culture—in disengaging embodied practices of mourning and burial, and instead gentrifying death in memorial services that merely “celebrate life”—is forgetting what Ireland still knows well as a certain gritty engagement and accompaniment at the end of life. “When we estrange ourselves from our dead,” Lynch said, “we are estranging ourselves from Humanity 101.”

Lynch connected these reflections to his own Irish-American family’s experience stretching back to the mid-20th century. He displayed a family photo from 1934 (reproduced here) showing the extended Lynch family gathered on the steps of St. John the Evangelist Church in Jackson, Michigan. There, a young priest, Rev. Thomas P. Lynch (Lynch’s great-uncle and namesake), had just celebrated his first Solemn High Mass. The priest’s father, Thomas C. Lynch, had passed away, but it was his marriage to a fellow immigrant, Ellen Ryan, that would make possible a new life in America for future generations of Lynches.

That new life, though, would include times of sadness as well as joy. Two years after his ordination, the young Father Thomas died of pneumonia while serving Native Americans in Taos, New Mexico. Edward P. Lynch, the priest’s 12-year-old nephew, found himself wandering the Desnoyer Funeral Home in Jackson, Michigan, as the family made arrangements for the wake and funeral. Unnoticed, the boy happened upon two undertakers silently dressing his uncle’s body in his priestly vestments and carefully lifting him into a casket. Profoundly moved in that moment, Edward would grow up to become a funeral director. His three sons, including Thomas P. Lynch, would carry on that work years later. Besides adopting his father’s profession, Lynch became a writer and educator, inspired by the likes of Heaney and O’Driscoll on his initial visit and many returns to Ireland in search of his ancestral heritage there.

Updated March 10, 2017