Sergio González

Sergio González

Sergio M. González is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he specializes in labor history, immigration history, Chicano/Latino history, and the history of the Midwest, along with religious history. He was awarded a 2017 Research Travel Grant from the Cushwa Center for his project “I Was a Stranger and You Welcomed Me: Latino Immigration, Religion, and Community Formation in Milwaukee, 1920–1990,” which investigates the links between Latino immigrants’ faith and social activism.

Catherine Osborne conducted the following email interview with González in late June.

CO: What got you interested in this topic? What has it been like to do research on your own community?

SG: Entering graduate school, I originally defined my research project broadly as a labor history of Milwaukee’s Latino community. My parents are both originally from Jalisco, Mexico, and I felt a strong sense of needing to understand what might drive immigrants from a central Mexican state to emigrate to the Great Lakes region. Besides Marc Rodriguez’s superb The Tejano Diaspora: Mexican Americanism and Ethnic Politics in Texas and Wisconsin (University of North Carolina Press, 2011), there wasn’t much published scholarship on Wisconsin, so I knew I could also help fill some larger historiographic gaps.

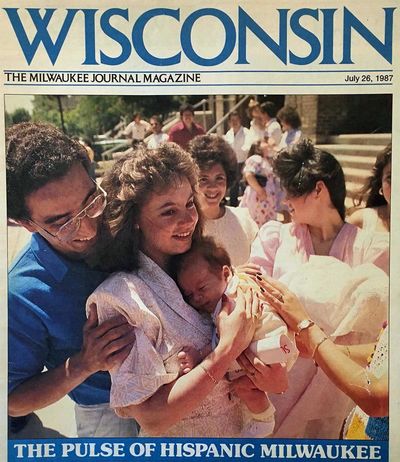

July 26, 1987, cover of Wisconsin, The Milwaukee Journal Magazine

July 26, 1987, cover of Wisconsin, The Milwaukee Journal Magazine

During my first archival trip to the Milwaukee County Historical Society, I came across a full-page image from one of the city’s newspapers of record, the Milwaukee Journal. I found myself staring at a photo of myself, a baby just a few months old, in my parents’ arms as we exited Our Lady of Guadalupe-Holy Trinity Church, a Catholic parish on Milwaukee’s Latino near south side. Emblazoned below the picture was the subtitle, “The Pulse of Hispanic Milwaukee.” The text pushed me to consider what it meant to have an image of people exiting the city’s most important Spanish-serving Catholic congregation as the lead for a story on Milwaukee’s ever-growing Latino community. That newspaper cover, along with my continued reading in Latino and religious history, has driven my desire to better understand the role of religion in community formation among Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Central American populations in Milwaukee.

CO: You’ve done a lot of oral history. Have you found that your archival work at Notre Dame has backed up and filled out what you learned from the oral histories, or are you getting a somewhat different picture (or both!)?

SG: Both! Wisconsin’s Latino communities have unfortunately been criminally under-archived, creating large silences within the traditional documentation of personal papers and governmental records often found in state historical societies and libraries. My early research trips were sometimes maddening and often left me a bit despondent, as archivist after archivist halfheartedly shrugged and said, “I’m sorry, but we just don’t have much saved on that population.” It’s unfortunately not a problem particular to Wisconsin’s Spanish-speaking community, as many scholars who study communities of color might tell you, but the lack of resources did initially leave me wondering how I could tell a story that I knew existed but just hadn’t been documented. Luckily, I’ve had academic mentors who have supported my work in oral history to fill in those silences and unearth these histories.

Historian Gary Y. Okihiro reminds us that oral history serves not only as “a tool or method for recovering history,” but also as “a theory of history which maintains that the common folk and the dispossessed have a history and that history must be written.”[1] Every interview I’ve conducted not only illuminates larger narratives that I’m able to weave into my research, but also adds to a (thankfully) growing archival base memorializing Wisconsin’s Latino communities. As I’ve dug deeper into my dissertation, I’ve uncovered more and more organizational records and state commission reports that help me understand the economic and institutional structures that defined Latinos’ immigration and settlement in Wisconsin, but I’ve found that oral history offers one of the only true portals to delve into the social and personal lives of those who made Milwaukee home.

CO: Do you see Milwaukee’s Latino/a activism as being a mirror or an offshoot of activism in the Southwest—California and Texas—or is it more homegrown? What makes it distinctive?

SG: There were certainly strong links between the activism that flourished in Milwaukee in the late 1960s and early 1970s and movements in areas with larger Latino populations like California and Texas, and historians like Marc Rodriguez have expertly pointed those out for scholars to follow. As Rodriguez notes, the migrant farmworker unionism of César Chávez and the United Farmworkers and the historic political activism that flourished in Crystal City, Texas both heavily influenced indigenous and transplanted movements in Milwaukee throughout the period.

While tracing those linkages, I’m perhaps more interested in learning what made Milwaukee distinct, specifically by understanding the pan-Latino nature of activism throughout the period. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, Milwaukee witnessed the growth of Mexican native, Mexican American and Chicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Central American communities, each of which brought its own understanding of advocacy, social and economic justice, and faith that defined Milwaukee’s various movements. During a multi-year period of vibrant activism, Milwaukee Spanish-speakers of different national and documentation backgrounds successfully navigated interethnic cultural and political differences to connect their battles under a common banner, fighting for employment opportunities, educational equity, and welfare rights, as well as against police brutality and unjust immigration policies. Chicano activist Ernesto Chacón explained to the Milwaukee Journal in 1970 that every Milwaukee Latino deserved a seat at the table: “We think the community – the whole community – is important. Everybody ought to be able to help decide what we ought to be doing and who should do it.”[2]

1971 Proceedings of a conference held in Milwaukee

1971 Proceedings of a conference held in Milwaukee

In Milwaukee, Latino civil rights activists also engaged the city’s religious community in public debates throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s over clergy and churches’ obligations to fight side-by-side with social justice movements. While a minority within the community did accuse city churches of being completely irresponsive to Latinos’ needs and thus irrelevant to social justice initiatives, for most, the fundamental question centered on how churches could do more to assist the city’s Spanish-speaking groups. Milwaukee Latinos, including young radical Chicanos and Puerto Ricans, expected that Catholic parishes and Protestant churches and the clergy that led them would be recognized voices in their struggles. Milwaukee’s young Latino activists thus did not ignore churches – they actively engaged with them to reform essential community institutions and make them attentive to the needs of the city’s Spanish speaking.

CO: Are you seeing organic links between Milwaukee’s sanctuary movement of the 1980s and today’s incipient sanctuary movement?

SG: When I began research on Milwaukee’s 1980s Sanctuary Movement a few years ago, I never imagined that my scholarship would become so relevant in 2017. The final section of my dissertation charts the growth of this movement, an interfaith, interracial, and interclass effort to support Central American refugees who had fled destruction in their homeland and sought legal asylum in the United States but found an American government unwilling to follow international human rights law and properly adjudicate their cases. Religious congregations and organizations of nearly every faith, heeding a moral calling to welcome the stranger, joined together to open their doors as places of sanctuary for refugees, often in defiance of federal immigration law.

In December of 1982, less than a year after the start of the movement at Tucson, Arizona’s Southside Presbyterian Church, Catholic churches in Milwaukee became the first of their faith to join the movement, and did so with the blessing of Archbishop Rembert Weakland. Along with the countless lay and clergy who made the movement run, the Catholic episcopal leader was joined by Wisconsin’s Lutheran Bishop Peter Rogness and Episcopal Bishop Roger White, who all proved willing to denounce a presidential administration that advocated immigration and foreign policies inconsistent with support for the poor, destitute, and those who had been forced to the margins of society.

There are of course distinctions to be drawn between the 1980s movement and the “new” sanctuary movement that has grown tremendously since last year (the Church World Service recently noted that the number of congregations offering sanctuary or supporting the movement has doubled to more than eight hundred following November’s presidential election). Perhaps most obviously, the population needing support has changed and now consists of a more global, undocumented, immigrant population. The spirit guiding these endeavors, however, remains the same. Religious leaders and communities view their faith and involvement in Sanctuary through a lens of social justice, understanding their participation in the movement as a deed of faith as well as a political action. In my conversations with congregations discerning their role in protecting undocumented communities today, I’ve watched lay and clergy turn to Scripture to justify civil disobedience against immigration enforcement policies they consider both morally and legally unjust and in violation of both higher and earthly power, much like those involved in the 20th century once did. Participants in the 1980s movement and today’s emerging resurgence thus both see their participation in the Sanctuary Movement as unconcealed acts of faith that move to shift the moral compass of our nation.

CO: We talked a lot about lay-clergy interaction. What has the relationship between Latino/a lay activists and priests, bishops, and religious been like in Milwaukee? Did it change significantly during the course of the 1920–1990 period your dissertation covers?

SG: The relationship has certainly changed throughout the 20th century, but one of the contributions I hope my project makes to the historiography is demonstrating that connections between Latino laity and U.S. clergy, and just as importantly between Latino laity and episcopal leadership, were always present, often shifting, and even at times evolving towards meaningful collaboration. Past scholars of Latino settlement in the United States have too readily dismissed churches as either being neglectful of Latino communities or of being strictly vehicles for the assimilation of Spanish-speaking populations into the American mainstream. Latino Milwaukee’s history, however, provides us with a much more dynamic story, one that points to a dialogue within faith communities that was at times contentious and combative but could also often be cooperative. Throughout the 20th century, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Central American immigrants and migrants challenged the city’s religious leaders to be ever more responsive to their communities’ economic, social, and cultural needs. In the process, Latinos of different Christian faiths adopted and promoted interethnic and interracial fellowship within Milwaukee’s churches to mitigate prejudice and social alienation, provide sanctuary from nativism and repression, and foster local and transnational community building in the name of shared religiosity.

By weaving the narratives of Latino immigration into Milwaukee’s historical fabric, my project attends to the way racial-ethnic divisions created distinctions in the integration of immigrants into religious spaces while also tracing the congruencies between their incorporation experiences. Expressions of interethnic and interracial community, though fluid and contingent, had the ability to cut across lines of difference defined by categories of nationality or immigration status. What began in the 1920s as a project to create a mission chapel for the city’s fledgling Mexican community matured into aid programs for Mexican and Puerto Rican migrant workers in the 1950s, movements for social and economic justice through the Chicano and Young Lords movements in the 1960s, and interfaith efforts to support Central American refugees through the Sanctuary Movement in the 1980s. Latino immigrants of all nationalities, who faced discrimination in schools, work sites, and social services, worked with clergy and episcopal leadership to create faith-based and ethno-racial identities within the city’s religious spaces. Throughout the 20th century, a growing population of Latinos of diverse national backgrounds and immigration statuses challenged Milwaukee’s religious leaders to be ever more responsive to their communities’ economic, social, and cultural needs, and in the process transformed the city’s religious spaces and institutions into vehicles for community formation and collective social change.