On Friday, February 10, the Cushwa Center and Play Like a Champion Today (PLACT), a non-profit organization dedicated to cultivating youth athletics, jointly welcomed historian Timothy B. Neary to Notre Dame for a lecture entitled “For God and Country: Bishop Sheil’s Vision for Youth Sports.” Neary is associate professor of history at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island. He recently published a book, Crossing Parish Boundaries: Race, Sports, and Catholic Youth in Chicago, 1914–1954 (University of Chicago Press, 2016), on Bishop Bernard Sheil’s founding of the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO). After his presentation, a panel discussion explored aspects of Bishop Sheil’s contemporary relevance, and PLACT hosted a “Youth Sport Summit” the following morning to reflect further on renewing the mission of Catholic athletic programming with Sheil as a model. More than 30 youth sports leaders from 20 cities traveled to South Bend to participate.

James Bernard Sheil, Jr., was born in 1886 in Chicago, the only child of a middle-class Irish Catholic family. In high school, he found himself captivated by sports and by the principles of Catholic social thought. Although talented enough to play baseball professionally, he instead entered the priesthood and was ordained in 1910. He became a protégé of Archbishop George Mundelein of Chicago and was named auxiliary bishop in 1928. Still, Sheil never lost his love of athletics, Neary said. Influenced by the originally Protestant ideal of muscular Christianity, he “worked to create an image of robust virility” through his ongoing participation in sports, going so far as to participate in boxing training sessions while still in his cassock.

This love of sports drove Bishop Sheil to found the CYO in 1930. Neary traced the foundation of the CYO to Mundelein’s instruction that Sheil establish a program that would attract Catholic youth and keep them from seeking recreational activities elsewhere. The CYO also arose out of Sheil’s personal sense of obligation to the young people he had encountered as a jail chaplain, and whom he believed might otherwise become delinquents. He also worked in response to Catholic social teaching, which “obligated him to fight against social injustice when he saw it.” Known as “the Apostle of Youth,” he designed the CYO’s citywide programming to inspire a “true love for God and country” in the children who participated—boys and girls, blacks and whites, Catholics and non-Catholics.

Neary identified four key aspects of Sheil’s approach to youth sports that made the CYO in Chicago successful. First, Sheil felt he was responding to an urgent need: combatting juvenile delinquency while steering young people away from the Protestant influences of the YMCA and other non-Catholic programs. Sheil and many other social reformers were concerned about the growth of “consumerism, secular temptations, and materialism” in a modern city where the high unemployment rates of the Depression joined with the expansion of radio, movies, comic books, and other mass media to exert significant pressures on those tasked with educating young people. Sheil argued that “the [Catholic] church should employ organized recreational and leisure activities to promote Christian and democratic principles among youth.” Sports would help children avoid idleness while building “character.” These goals, Neary pointed out, fit well into an American Catholic culture that valued the formation of children. Since “bishops viewed American-born children as providing a link between priests and their immigrant parents,” a focus on forming the hearts and minds of children to be both American and Catholic was critical.

The second key aspect of Sheil’s approach was his pragmatism. While recognizing the problematic quest for glamour characteristic of mass culture, the CYO used that same enticement to promote its programs, especially through boxing. Neary pointed out that the Golden Gloves, an amateur boxing tournament established in 1928, served as the model for Sheil’s boxing tournament; the bishop even hired famousboxing professionals to coach. CYO boxers could get a measure of fame in their own right, with championships drawing tens of thousands of spectators. Although the centrality of violent fighting to the CYO led to criticism, Sheil argued that it worked to keep young men away from even more morally dangerous pursuits: “Show me how you can lead boys from saloons with a checkers tournament,” he said, “and I’ll put on the biggest checkers tournament you ever saw.”

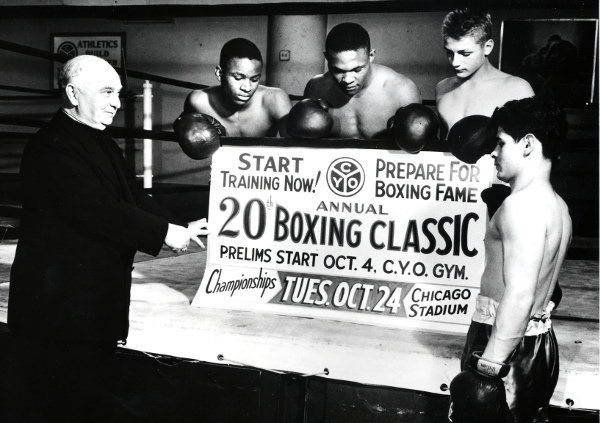

Bishop Sheil and boxers promoting the CYO tournament in 1950, courtesy of the Archdiocese of Chicago’s Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center

Bishop Sheil and boxers promoting the CYO tournament in 1950, courtesy of the Archdiocese of Chicago’s Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Archives and Records Center

Inclusivity was the third mark of Sheil’s approach. Under Sheil, the CYO not only allowed for participation from a variety of ethnic and national backgrounds but also actively promoted itself as a “melting pot.” The CYO’s model, which assembled teams by parish, reflected the Archdiocese of Chicago’s strategy of forming ethnic or national parishes, with African-Americans in their own “national” parishes alongside Irish, Polish, Italian, and other European ethnic parishes. Neary observed that this strategy of representing all the city’s major ethnic groups mirrored wider American pluralistic ideals of the mid-20th century. He also noted that, with Chicago’s Democratic machine politics controlled by Irish Catholics, participation in CYO sports programs offered a number of black Chicagoans entree into business and political life.

Finally, Neary pointed to Sheil’s conviction of the link between civic virtue and religious practice. The CYO Pledge, for example, was recited by 15,000 fans along with 32 boxers at a 1931 tournament:

I promise on my honor to be loyal to my God, to my Country and to my Church; to be faithful and true to my obligations as a Christian, a man, and a citizen. I pledge myself to live a clean, honest, and upright life—to avoid profane, obscene, and vulgar language, and to induce others to avoid it. I bind myself to promote, by word and example, clean, wholesome, and manly sport; I will strive earnestly to be a man of whom my Church and my Country may be justly proud.

Influenced by the Catholic Action movement, Sheil expanded the scope of the CYO program beyond sports into music, social services, and adult education. But the linkage between sports, Catholicism, good character, and civic virtue remained his driving conviction.

Neary argued that Sheil “complicates our understanding of white ethnics during the interwar period,” revealing an era in which cosmopolitan, pluralist values were important to many people within the Catholic Church. After the war, however, as white Catholics moved in great numbers to the suburbs and were increasingly replaced by African-American and Latino families in the city, white ethnic Catholics increasingly saw the CYO as being dominated by racial minorities and withdrew. Meanwhile, Sheil was aging, and a new diocesan administration was less committed to the CYO. In 1955, the CYO’s centralized office disbanded and programs were parceled out to different offices across the archdiocese. Neary concluded by suggesting that, while “the CYO was far from perfect and by no means a panacea for all that ailed the communities it served,” a recommitment to its pragmatism, its embrace of ethnic, racial, and religious diversity, and its use of the appeal of athletics to “advance civic engagement rooted in religious convictions” could serve many communities today.

Panelists (left to right) Clark Power, Dobie Moser, Kristin Sheehan, and Mary Ann King

Panelists (left to right) Clark Power, Dobie Moser, Kristin Sheehan, and Mary Ann King

Neary’s lecture was followed by a panel discussion featuring staff and partners of PLACT. Clark Power, founding director of PLACT and professor of psychology and education in Notre Dame’s Program of Liberal Studies, pointed out that Bishop Sheil was well ahead of the professional psychologists of his time, in that he rejected seeing troubled children as “broken” and instead focused on a positive vision of forming youth. He was also bold, chiding his fellow clergy for being too “prudent” in avoiding Catholic teachings that would appear impolitic, namely, those on the brotherhood of man and the love of God for the poor. Power argued that Sheil’s vision of sports as an opportunity for moral, religious, and civic education remains relevant today, but was concerned that youth sports often exclude children in poorer neighborhoods. He expressed hope that Sheil’s example would impel Catholic youth sports to challenge, rather than reflect, ongoing residential and educational segregation.

Kristin Sheehan, program director at PLACT, praised Neary’s book as an opportunity for many contemporary CYO and other Catholic athletic directors to learn some of the history behind their programs. Like Power, she encouraged today’s CYOs to paymore attention to underserved children, which might require coordination at the diocesan level to promote opportunities across parish boundaries. Quoting Gregg Popovich, coach of the San Antonio Spurs, she pointed out that lack of access to facilities, equipment, and travel teams is especially detrimental to minority and poor children. She also spoke about PLACT’s effort to take Pope Francis’ advice and use sports as a way of promoting peace, citing his most recent general audience, in which Francis issued a widely reported appeal “not to build walls but bridges.”

Mary Ann King and Dobie Moser, both from CYO Athletics for Catholic Charities in the Diocese of Cleveland, concluded the panel by speaking about the structural challenges facing youth sports. Borrowing from Paul Farmer’s approach to global health care delivery, Moser said that successful programs have “space, staff, stuff, and systems,” and therefore require financial resources. King pointed out that today more than 46 million Americans live in poverty, 20 percent of whom are children. Only 15 percent of children living in homes below the poverty line play youth sports, due partly to lack of equipment and the absence of local teams. The Diocese of Cleveland has established a centralized fund to help pay for equipment, but Moser and King both argued that Catholics need to pay more attention to this kind of issue, especially in an era of shrinking funding for public school sports and afterschool programs. Moser said that Bishop Sheil’s “prophetic vision that all of the children”—not just the Catholics—“belong to us … needs to be the future of the CYO.” Otherwise, he said, “the CYO will provide more and more resources to a primarily white, affluent suburban population.” Instead, he argued, those involved in Catholic youth sports today should use Sheil’s example, as recovered in Neary’s Crossing Parish Boundaries, as an impetus to refocus on children who don’t already enjoy access to recreational programs.