Spring 2014 Lead Story

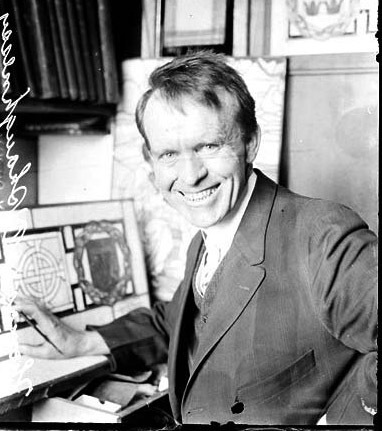

A Canvas of Light:

Tracing the Artistic Vision of Thomas O’Shaughnessy

By Ellen Skerrett

On May 10, 2013, the granddaughters of artist Thomas Augustin O’Shaughnessy embraced each other with emotion as the archives van pulled away from a hotel in Glenview, Illinois, for its return trip to South Bend. After a year of long-distance discussions and a personal visit to Notre Dame, the family had agreed that the best way to honor the life and legacy of “Gus” O’Shaughnessy (1870–1956) was to make his papers available to scholars by providing access through the Hesburgh Archives. As young women, Kate, Meg, Brigid, and their sister, Beth (1956–2000), recognized the pride their late father, Joseph, took in caring for the small collection in their Wilmette home. It’s a poignant reminder that before they became “rare, unique, and uncommon research materials” at Notre Dame, these historical documents were cherished family heirlooms.

I joined the O’Shaughnessy sisters and their mother on a Sunday afternoon during the week they spent together organizing the donation. Voices from the past found in news clippings and correspondence mingled with stories about the legendary Chicago artist. In 1995, a Chicago Tribune feature attempted to sum up the genius of Thomas O’Shaughnessy with the headline, “He did windows,” but his career was far more complex.

An enthusiastic supporter of the City Beautiful Movement, he organized the first Columbus Day celebration in 1911, which the Tribune characterized as “an expression of our new civic consciousness.” At the same time he served as a member of the city’s Art Commission, O’Shaughnessy worked to acknowledge the legacy of Father Jacques Marquette, reconnecting Chicago with its Jesuit roots. A lover of history, the artist featured President Abraham Lincoln in one of his 40 windows for the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Springfield, the capital of Illinois, in 1928. He won the artistic competition for the first International Eucharistic Congress in Chicago in 1926 and was deeply involved in the 1933 World’s Fair.

To understand the man and his body of work it is helpful to remember how much he challenged traditional Catholic notions of art. A century ago, when Irish Catholic congregations in Chicago and in major cities across the nation favored Gothic-style churches as signs of respectability, Thomas O’Shaughnessy transformed the mother parish of the Chicago Irish into the best-known example of Celtic Revival Art in America. Unlike the Honan Chapel at University College Cork (1916) whose Celtic ornament and decoration were part of its original design, Old St. Patrick’s dated from 1856 and its interior had been completed in stages, as finances permitted. Its main altar, for example, crafted by Sebastian Buscher,

featured a towering statue of St. Patrick as well as numerous angels. As in so many Catholic parishes of limited means, the wooden altar was painted white to give the illusion of marble.

Never located in a fashionable residential neighborhood, by 1912 the Romanesque structure at Adams and Desplaines streets was surrounded by manufacturing buildings and warehouses. Had St. Patrick’s been a Protestant congregation or a Jewish synagogue, it would have been demolished, but in Chicago, the Catholic connection

Never located in a fashionable residential neighborhood, by 1912 the Romanesque structure at Adams and Desplaines streets was surrounded by manufacturing buildings and warehouses. Had St. Patrick’s been a Protestant congregation or a Jewish synagogue, it would have been demolished, but in Chicago, the Catholic connection

to sacred space defied economics. O’Shaughnessy breathed new life into the city’s oldest public building over the next decade, creating luminous windows of colored opalescent glass and intricate Celtic stencils on the walls and ceiling.

In a radical break with the conventions of his day, O’Shaughnessy looked to Ireland’s past for inspiration. Later in life he would claim that during a 1905–1906 trip to Europe he was one of the last people allowed to sketch directly from the Book of Kells at Trinity College, Dublin. Whether myth or fact, his 1913 canopy over the main altar, composed of more than 50,000 pieces of “translucent mosaic enamel glass,” bears a striking resemblance to the Four Evangelists in the ancient illuminated manuscript. During a lecture to the American Institute of Graphic Arts in New York in 1917, Dr. James J. Walsh ascribed the dramatic change that had taken place in St. Patrick’s “dingy interior,” to “the influence of the Book of Kells all over the walls.”

Born in Newhall, Missouri, on April 14, 1870, to James O’Shaughnessy, a Famine immigrant, and his Irish-American wife,

Catherine Mulholland, young Thomas attributed his interest in Celtic art to the influence of Sister Ledwina at the Loretto Academy in Kansas City. But as Timothy Barton notes, it may have been his family’s visit to the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago that fired his imagination and his determination to establish himself as an artist. On display at the White City were reproductions of the Ardagh Chalice, the Bell of St. Patrick, and the Cross of Cong fabricated by Edmond Johnson. It is also possible that O’Shaughnessy was influenced by Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building with its colorful interlace ornament.

What makes O’Shaughnessy’s artistic career so intriguing is that he first achieved success as an illustrator; by 1902 his drawings were being exhibited in Chicago along with those of his fellow cartoonist, John T. McCutcheon. In the 1890s before photographs became commonplace in daily newspapers, sketch artists provided readers with detailed views of urban life. Through the years while doing research on Jane Addams, I’ve come across O’Shaughnessy’s distinctive signature on cartoons and illustrations, but few, if any, found their way into his collection. Perhaps he was too busy as a newspaper illustrator to save his work. Or he may have considered them ephemera and unremarkable. After all, his contemporary, Finley Peter Dunne (1867–1936) did not include his Chicago “Mr. Dooley” pieces in his collected works, and they were all but forgotten until Charles Fanning rediscovered them in the early 1970s.

O’Shaughnessy’s most famous sketch appeared in the Chicago Daily News on December 31, 1903. As one of the first journalists to arrive in the aftermath of the fire at the Iroquois Theater on Randolph Street, he provided a rare eyewitness account of the tragedy. During a performance of Mr. Bluebeard, scenery in the modern “fire-proof” theater shot “tongues of flame” into the audience, killing more than 600 people, mostly women and children. In contrast to other coverage showing firefighters carrying bodies, O’Shaughnessy’s sketch is extraordinary for its sacramental dimension: in deft strokes he captured Police Chief Francis O’Neill holding a lantern as Bishop Peter Muldoon anointed victims.

There’s plenty of work to be done by scholars interested in tracing the artistic vision of Thomas O’Shaughnessy that began in earnest at Old St. Patrick’s and continued for more than 40 years. We know from contemporary sources that the large bronze Celtic cross affixed to the Chicago church in 1912 signaled his intention to reimagine this sacred space as “the first example in America of the renaissance of Irish art in sculpture, in painting and in translucent mosaics.” But as it turned out, his commission also became personal when the 46-year-old O’Shaughnessy fell in love with the pastor’s 25-year-old niece, Brigid McGuire, managing editor of the weekly Irish paper, The Citizen. According to one account, Thomas couldn’t forget the blue of her eyes and incorporated the color into his design for the windows. Tragically, Brigid O’Shaughnessy died in the flu epidemic of 1919, less than three years after their marriage.

It should come as no surprise to historians that Catholic parishes such as St. Patrick’s did not document O’Shaughnessy’s commissions (or payment thereof), nor did the artist leave records from his studios at 108 N. State Street or 224 W. Superior Street. In editing a book on Old Saint Patrick’s in 1997, I was grateful to find articles about the church in the files of the Chicago’s Catholic diocesan paper, The New World, but the various pastors received more ink than the artist.

One of the paradoxes of American Catholic history is that the church environment that so profoundly shaped the daily experience of ordinary people, generation after generation, remains largely a backdrop. This is curious because for the Irish in Ireland as well as immigrants to the United States, “brick-and-mortar” Catholicism after the Great Famine was a subject of great interest, and newspapers routinely published crucial information about architects, building materials, and dimensions. It is a cause for celebration that the increasing digitization of newspapers as part of the Catholic Research Resources Alliance (CRRA), and the Catholic Portal (www.catholicresearch.org) will enable researchers to reconstruct the way in which Catholics used their churches to put their imprint on the urban landscape throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th.

Present-day worshipers at St. Patrick’s continue to marvel that O’Shaughnessy’s windows remain luminescent at night, bathing the church with brilliant light. According to one newspaper account published in the 1940s, he mixed fine quartz sand from Ottawa, Illinois, with metallic oxides, fabricating the windows in Kokomo, Indiana. While it may be impossible to document the “medieval pot-metal process of staining glass” that O’Shaughnessy revived a century ago, researchers may have more luck tracing the patent he secured in 1926 to make refractory glass. When it came to subject matter for his windows in St. Patrick’s, O’Shaughnessy subverted the old adage, “No Irish Need Apply.” Not a single window recalls the Immaculate Conception, the Nativity of Christ, the Feast of Cana, or the Crucifixion and Death and Resurrection of Jesus. Instead, the artist honors St. Patrick and Brigid (two windows each) and saints who were hardly household names among the American Irish: Finbar, Colman, Sennan, Columbanus, Attracta, Columbkille, Brendan, Carthage, and Comgall. There is even a window dedicated to Brian Boru, the first high king of Ireland.

O’Shaughnessy’s depiction of St. Brigid is extraordinary on several levels. First and foremost, the artist has restored Ireland’s patron saint to her preeminent role as educator. Brigid, known as “St. Mary of the Gaels,” was born c. 140 the daughter of a slave,but Brigid learned to read and write and founded a monastery. In a full-length window at St. Patrick’s she is seated at a desk with a quill in hand, creating what appears to be an illuminated manuscript. Behind her, perhaps for inspiration, is an angel. O’Shaughnessy didn’t stop there, portraying Brigid in a second window as teacher, a reminder of the role women have played in the transmission of Irish identity, religion, and culture.

At the time O’Shaughnessy was growing up, the name Brigid had fallen into disfavor among Irish Americans, a reaction to the stereotype of Bridget the domestic. A familiar figure of fun on the stage, the Bridget caricature took on ominous tones during the height of the 1880s Land League campaign in Ireland. Puck cartoons were especially vicious, tracing the evolution of Bridget the cook from a “shanty” in Ireland to her tyranny in the kitchen of middle-class households in America. In “The Irish declaration of independence that we are all familiar with,” Bridget raises a muscled arm to the woman of the house as dinner burns in the oven, a pot boils over, and shards of crockery lay between them.

Behind these stereotypes was a deeper reality: Irish immigrant women regarded domestic work as a crucial first step on the road to upward social mobility. Moreover, they became links in chain migration, using their earnings to pay for the passage of brothers and sisters to America and to send remittances to care for aging parents in Ireland. Many families refused to christen their daughters with a “maid’s” name, and counseled female Bridgets from Ireland to use their middle names instead as they searched for employment. Whether O’Shaughnessy consciously set about to reverse the stereotype of Bridget in his windows at St. Patrick’s is unclear, but at the time of their installation, Irish-American women in Chicago had become educators in significant numbers, both as Catholic sisters and as teachers in the public schools.

One of O’Shaughnessy’s greatest friends and admirers was the Rev. John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, president of the University of Notre Dame from 1905 to 1919. Among the cherished documents in the O’Shaughnessy collection is a September 17, 1917 letter from the president, thanking the artist for redesigning the cover of Scholastic magazine and enclosing a check for $25, “desolated that I cannot make it $2500.00.” It was no doubt a sentiment shared by Brigid and Thomas O’Shaughnessy whose first child, Mary Attracta, had been born on July 3. As an artist who apparently lived from commission to commission, O’Shaughnessy needed patrons, and Father Cavanaugh promised to help by “talk[ing] to every priest that I meet, if there is any possibility of getting him interested.” In an editorial note in the 1917 diamond jubilee issue of the Scholastic, Notre Dame’s president expressed hope that “some wealthy lover of things Catholic, Irish and beautiful might endow a chair at the University in order that Mr. O’Shaughnessy might be with us always and become the founder of a new school of art.”

The fact that O’Shaughnessy continued his career without major financial and institutional support may explain in part why he did not become better known, but what about his determination to create stained glass windows for Catholic churches? There is no question that he could execute secular installations such as his windows for the Elks Temple in New Orleans (c. 1910) and the 1914 window for the Henry O. Shepard public school, financed by members of the Old-Time Printers’ Association of Chicago. But he seems to have regarded himself primarily as a Catholic artist whose vision of liturgical art was far ahead of his time.

A classic example is the Great Faith Window he created for St. Patrick’s, 25 feet in height, composed of more than 250,000 pieces of art glass. Its unusual Art Nouveau angels and female figures reflect the influence of O’Shaughnessy’s mentor and friend, Alphonse Mucha, but what renders this installation even more remarkable is its very modern subject matter. The first American memorial to Terence MacSwiney, it honors the Lord Mayor of Cork who died after a 74-day hunger strike in London’s Brixton prison on Oct. 25, 1920. Controversial in its day, the Faith window depicts MacSwiney as a martyr for Ireland, rising out of the flames of purgatory as his soul makes its way to heaven between “the fires of trial and persecution.” We know virtually nothing about O’Shaughnessy’s political views or how they evolved over time, but he has left a haunting reminder in vivid shades of opalescent glass that the struggle for justice has deep religious roots.

Through his long career, O’Shaughnessy never hesitated to destroy a stained glass window and begin again if its quality was imperfect. As Barbara O’Shaughnessy tells the tale, she and her husband, Joe, were newly married when they received a panicked call from the Rev. James J. Mertz, SJ. The Jesuit had all but given up hope of ever seeing the small windows “Gus” promised for the lower level of Madonna Della Strada chapel on Loyola University’s Lake Shore Campus in Chicago. The solution? Joe regularly invited his father over for dinner—with the caveat that he had “better bring a window for Father Mertz!”

-------------

Ellen Skerrett is the Chicago-based historian/researcher for volumes 2 and 3 of The Selected Papers of Jane Addams, ed. Mary Lynn Bryan. She has written widely about the Chicago Irish and featured Thomas A. O’Shaughnessy in her 2005 Hibernian Lecture at the University of Notre Dame, “Creating Sacred Space and Reclaiming Irish Music and Art in Chicago.”