Sister Builders in Chicago

The “Crossings and Dwellings” exhibit at the Loyola University Museum of Art (LUMA) presented an unusual challenge to us as historians: How could we convey the substantial contributions to the Jesuit mission in Chicago made by the religious of the sacred heart (R.S.C.J.s) and the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (B.V.M.s), neither of which owned many art objects? Unlike their ordained male counterparts, the sisters had no golden monstrances or chalices nor any of the globes or maps and etchings that constituted such vivid examples of the Jesuit presence in the Midwest. the historical record, however, makes clear that the R.S.C.J.s and B.V.M.s collaborated closely with the Jesuits and were responsible for much of the growth of Chicago’s famed Holy Family parish during the 19th century. As historians, we aimed to put these remarkable women religious back “on the map” in a way that would engage visitors to the university’s art museum and begin a conversation about the sisters’ role in creating a Catholic education system in the frontier town on the shores of Lake Michigan. But in order to do so, we needed to identify material culture that would bring to life the accomplishments of “sister Builders” and reconnect their histories to the development of Chicago.

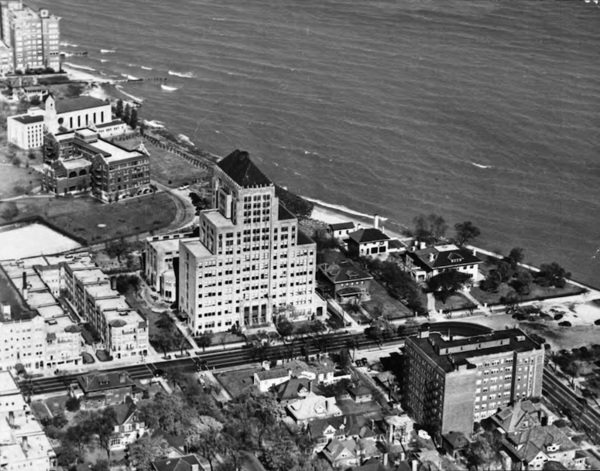

The B.V.M. Sisters broke ground for Mundelein College two days after the stock market crash in 1929 and employed crews around the clock as the Depression worsened. Classes began in September 1930, and the $2.5 million Art Deco skyscraper was officially dedicated on June 3, 1931. Courtesy of the Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago, Mundelein College Records Collection.

The B.V.M. Sisters broke ground for Mundelein College two days after the stock market crash in 1929 and employed crews around the clock as the Depression worsened. Classes began in September 1930, and the $2.5 million Art Deco skyscraper was officially dedicated on June 3, 1931. Courtesy of the Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago, Mundelein College Records Collection.

We began by reconstructing the footprint of the two women’s congregations in the Jesuit parish of the Holy Family on Chicago’s Near West Side to discover how their physical presence interacted with the neighborhood and parish. Like Father Arnold Damen, S.J., the founder of Holy Family, who was born in Holland in 1815, many of the sisters were themselves immigrants or the daughters of immigrants. The R.S.C.J.s, originally French, had established the first free school west of the Mississippi in 1818. Fifty years later members of the order opened a convent academy for young women in Chicago, and in 1860 their school building on Rush Street was floated down the south branch of the Chicago River to a site on Taylor Street in Holy Family parish. At a time when married women could not buy or sell or own property, the R.S.C.J.s purchased six acres of land and began the construction of a complex that by 1886 featured two massive brick structures, including a Gothic chapel designed by John Van Osdel, Chicago’s leading architect. Contemporary news accounts recorded the “imposing procession of forty drays and thirty five express wagons” that carried the R.S.C.J.s’ “ordinary household goods” on August 22, 1860. The original R.S.C.J. House Journal (written in French) not only commemorated this long-forgotten event in Chicago history, but it provided valuable context in room 203 of the Sisters’ partnership with the Jesuits.

In light of the invisibility of women religious in general, exhibiting G. P. A. Healy’s portrait of his daughter, Emily (1853-1909) as a novice in an R.S.C.J. convent in France allowed us to highlight the transnational Catholic narrative, now with a new gender focus, and made the case for the early participation of Roman Catholics in the cultural life of the antebellum Midwest city. Healy painted crowned heads of Europe as well as Abraham Lincoln (without a beard) and Chicago’s most prominent pioneer civic leaders and entrepreneurs. Until the LUMA exhibit, his daughter’s portrait had never been on public display. “Mother Healy” had attended the convent academy on Taylor Street as a child in the 1860s, and served her community as an educator for more than 30 years after her profession.

By 1890, 60 Sisters taught the daughters of Chicago’s elite in the Seminary of the Sacred Heart on Taylor Street and educated 1,000 poor girls in Holy Family parish, free of charge. In 1896 a beautifully ornate sanctuary lamp was commissioned for the Taylor Street chapel by R.S.C.J. alumnae and crafted in the studios of W. J. Feeley of Providence, Rhode Island. Inscribed with the names of 165 women who donated, it is a “Who’s Who” of early Chicago, both Catholic and Protestant, indicating the influence of Catholic women religious and their institutions in the cultural development of the leading citizens of the fast-growing metropolis. That Catholic sisters created and sustained a monumental sacred space in their educational complex raises important questions about the role of religion in urban life. It also challenges the popular narrative that identifies Jane Addams’ Hull-House, opened in 1889 not far from the R.S.C.J.s’ academic campus, as the only place of beauty and refinement on Chicago’s Near West Side, exclusively offering cultural opportunities to an impoverished slum neighborhood.

At the time this photo was taken, c. 1914, St. Mary's High School graduates were becoming Chicago public school teachers in such numbers that the Progressive Superintendent of Schools, Ella Flagg Young, tried to have a quota imposed. Courtesy of the Mount Carmel Archives of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Dubuque, IA.

At the time this photo was taken, c. 1914, St. Mary's High School graduates were becoming Chicago public school teachers in such numbers that the Progressive Superintendent of Schools, Ella Flagg Young, tried to have a quota imposed. Courtesy of the Mount Carmel Archives of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Dubuque, IA.

Room 205 of the “Crossings and Dwellings” exhibit, designed by Christopher S. Payne, traced the pioneering contributions of the B.V.M. “Sister Builders” to higher education in Chicago. Talk about an unknown story! The B.V.M. community began in Dublin in 1833 but within 10 years its members had “gone West” to Dubuque, Iowa, where they established their motherhouse. From the 1867 establishment of their first school in Holy Family parish, the congregation’s reputation as educators grew steadily, attracting students—and future B.V.M.s, among them Mother Isabella Kane (1855-1935), who played a crucial role in the design of Mundelein College’s Art Deco skyscraper on Sheridan Road.

Challenging Progressive reformers who insisted that vocational training was the ideal for immigrant children, the B.V.M.s opened St. Mary’s in 1899 as the first central Catholic high school for girls in the nation. One of its early graduates was Edith Redding (1889-1959), the daughter of a neighborhood saloonkeeper, who had been involved in drama productions at Hull-House. Although her portrait by Paris-trained artist Enella Benedict became one of the settlement’s iconic images, Edith’s identity remained a mystery until several years ago when Sister Mary A. Healey, B.V.M., made the connection, recalling that “Sister Sariel Redding always said her portrait hung at Hull-House.” The oil painting of “Edith,” on display in the LUMA exhibit, constituted a powerful reminder that religious life offered talented young Catholic women opportunities to shape a system of education that would enable others to achieve middle class status and professional life.

Rising 198 feet above North Sheridan Road, Mundelein College was the only college skyscraper in the world when it was dedicated in 1931. In 1991 the women’s college affiliated with Loyola University Chicago, and its Art Deco skyscraper is now the Center for Fine and Performing Arts. Accorded landmark status in 1980 by the Register of Historic Places, the Mundelein College building remains a site of cultural memory honoring women’s education and leadership. Courtesy of the Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago, Mundelein College Records Collection.

Room 205 dramatized the initiative and vision of the B.V.M. “Sister-Builders” as they put their imprint on the urban landscape of Chicago with The Immaculata high school (1922) and Mundelein College (1930), the first skyscraper college in the world. These institutions, built and paid for entirely by the B.V.M. order, were the result of collaborations between the sisters, architects, artists, and the male hierarchy. The preponderance of photographs in room 205, the use of carefully selected documents, and the combination of seemingly disparate artifacts—ranging from a rather traditional executive desk used by Sister Justitia Coffey, the first President of Mundelein College, to the extraordinary (and authentic) “Oscar” won by Mundelein graduate Mercedes McCambridge—was a carefully considered strategy on our part to ensure that the narrative of the B.V.M. “Sister Builders” operated on multiple levels. It allowed us to tell a complicated big story in limited space, and to reveal the B.V.M. agency and ownership of the narrative of women’s education in Chicago. The surrounding exhibit walls explored the role Mundelein College played in nurturing Catholic and American democratic values and citizenship for its students and faculty from the Great Depression to the Civil Rights Era. Illuminating this story was a documentary tracing the career of Ann Ida Gannon, B.V.M., from her student days at The Immaculata to her presidency of the college (1957-1975). Janet Sisler, director of the Gannon Center for Women and Leadership at Loyola University, commissioned Colleen Musker to create the video installation, incorporating rare archival photos from the Mundelein College collection.

One of the superficially quotidian artifacts on exhibit, Mother Isabella Kane’s “little black book,” highlighted both our narrative and our methodology. Small, and ordinary looking, a little leather loose-leaf notebook, this artifact became a window to the character, leadership, and agency of a rather self-effacing, undiscovered woman in the annals of American history. Born in Ireland in 1855, Mary Kane came with her widowed mother and five brothers to Holy Family parish in 1865. One of the most poignant items in room 205 was a reproduction of the 1880 U.S. manuscript census page identifying Mary’s mother as an illiterate who could neither read nor write. Mary Kane’s education with the R.S.C.J.s and the B.V.M.s set her on a very different path. She joined the B.V.M.s in 1870, rose steadily through the ranks, and was elected head of her order in 1919. Mother Isabella Kane oversaw the expansion of the B.V.M. educational network in the United States (which included 24 grammar schools and two high schools in Chicago by 1927) and she was instrumental in the planning of Mundelein College.

Mother Isabella’s little notebook records in great detail her engagement with every aspect of planning for the construction of the Mundelein skyscraper. It reveals how she planned the design of the interior, attending to the kind, quality, color, and placement of all the marble used in the interior space. Nearby we displayed selected letters of the official correspondence Mother Isabella kept with designers, artists, and architects involved with building Mundelein, offering rare insights into the character and quality of her leadership and providing more evidence of the independent spirit and authority of women religious.

We had few impressive, bejeweled or shiny objects to create a mood of awe-inspiring reverence, for B.V.M.s took their vow of poverty seriously and their self-effacing, collaborative, and cooperative form of leadership remained focused on the community, not individuals. Like most women religious, these “Sister Builders” did not maintain personal or private correspondence, journals, photographs, and diaries of a revealing nature, nor did they write autobiographies.

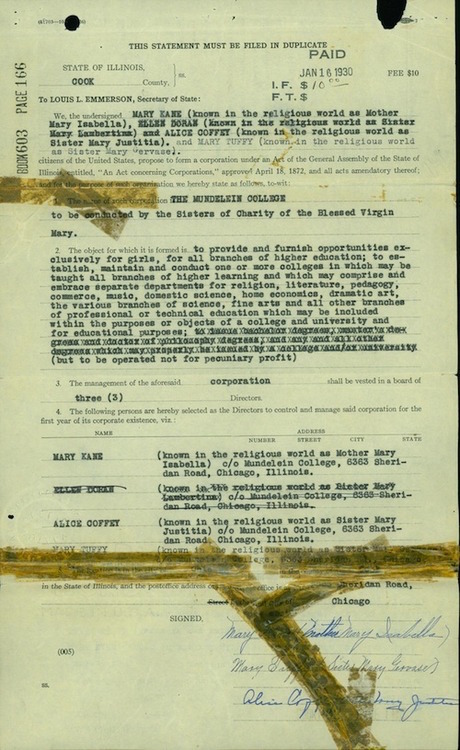

The incorporation papers of Mundelein College

The incorporation papers of Mundelein College

This brings us to a final note about choices we made in the exhibition space of Room 205: displayed near Sister Justitia Coffey’s desk are the incorporation papers of Mundelein College. This reproduction of the now fragile, held-together-by-scotch-tape document is signed by three women religious. In a politic and courteous gesture, the B.V.M. congregation named their unique and modern Art Deco skyscraper college for Cardinal Mundelein. His name, of course, is not on the document of incorporation. Built at the beginning of the Great Depression, with loans backed by the B.V.M.-high school properties of The Immaculata and St. Mary, the college opened in 1930 to great acclaim. It redefined the shoreline of Lake Michigan as it pioneered in modernizing education for the new American Catholic woman. Just as Room 205’s artifacts insisted on the presence and power of Catholic sisters in an area of the city seemingly dominated by Jesuit priests and Progressive reformers, the Mundelein skyscraper, now part of Loyola University’s Lake Shore campus, reveals as well as conceals the legacy of these Sister-Builders.

--

This article was first published in the History of Women Religious section in the Spring 2015 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.

American Catholic Studies Newsletter

Crossings and Dwellings Conference