Mitchell Oxford is a doctoral candidate in history at William & Mary. He received a Research Travel Grant in 2019 from the Cushwa Center for his dissertation project, “The French Revolution and the Making of an American Catholicism, 1789–1870.” In 2019, Oxford also gave a presentation on Catherine Spalding and the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth at the 11th Triennial Conference on the History of Women Religious, hosted by Cushwa at Saint Mary’s College. Peter Cajka caught up with Oxford about his project after his research visit to the Notre Dame Archives.

Peter Cajka: How does moving the French Revolution from the periphery to the center reshape the story we tell about American Catholicism? How does it change our narrative about Catholic immigrants, or concepts like liberalism, democracy, and religious freedom in the early United States?

Mitchell Oxford: That is the big question! In my dissertation, I argue that the French Revolution and its consequences are central to the emergence of a vigorous, growing, and increasingly self-confident American Catholicism in the 19th century. But I also see its effects in the resurgence of anti-Catholicism in antebellum America, as well as in a host of conflicts among American Catholics themselves.

To get us there, I think it’s important first to survey the enormous consequences of the French Revolution—to appreciate why it so transfixed Catholics throughout the world, and how it shaped the American Church.

At a time when American Catholics amounted to perhaps thirty or forty thousand souls—a sliver of the United States’ four million citizens—the Kingdom of France was Europe’s preeminent Catholic power, with roughly 28 million subjects on the eve of the Revolution in 1789.

In short order, revolutionaries disestablished the Church, confiscated its land, eliminated its tithes, abolished monastic orders, closed convents, shuttered seminaries, and required clergy to swear a civic oath anathematized by Pope Pius VI. Amid increasing violence toward priests, nuns, and faithful laity, the National Assembly executed Louis XVI—a monarch who had styled himself “Most Christian King”—in January 1793.

The Revolution continued to radicalize. The newly-christened French Republic embraced (short-lived) efforts to dechristianize French culture, while its armies carried out brutally punitive campaigns against Catholic and royalist counterrevolutionary holdouts within France, and took on seemingly all of Europe’s monarchies at once—including the Papacy—and won. Terror became domestic policy, culminating in the Reign of Terror carried out by the Jacobin leader Robespierre, in which thousands were guillotined in the uncompromising pursuit of a mercurial general will. As this republican project gave way to empire under Napoleon, two successive Popes were made French prisoners: Pius VI died in exile in 1799 and Pius VII was liberated during Napoleon’s fall in 1814.

From the perspective of those experiencing these events—and to contemporary scholars of modern Europe—the sweeping significance of the French Revolution was unmistakable.

From ideas about egalitarian citizenship, individual rights, and popular sovereignty epitomized in the motto “liberté, égalité, fraternité” and spelled out in “The Rights of Man and of the Citizen”; to efforts to rationalize the world through sweeping reforms to the legal code, administrative districts, taxation, weights and measures, and even the calendar; to a generation of warfare that sought to export these ideals—and French hegemony—from the Mississippi to Moscow; and to the emergence of powerful ideologies such as nationalism, liberalism, and conservatism in the Revolution’s wake, the dramatic events in France from the fall of the Bastille in 1789 to Waterloo in 1815 seemed to spawn the whole project of modernity.

And for many Catholics across the Atlantic world, the most significant and enduring results of the French Revolution were the new notions about church-state relations, religious liberty, and secularity—implemented and advanced by the French state, enforced at the point of a sword, and accompanied by popular hostility toward the Church.

Generations of Catholic conservatives rejected this revolutionary legacy wholesale; their inflexibility perhaps most dramatically expressed in the 1864 Syllabus of Errors, in which Pope Pius IX denounced the idea that he should “reconcile himself . . . with progress, liberalism, and modern civilization.”

But Catholic Americans were among the leading voices seeking to square their ancient faith with the modern values born of revolution. For Catholics in 19th-century Europe, the very concept of modernity would always be saddled by associations with the irreligion and anarchy of the French Revolution’s most radical moments. But Catholics in the early United States had experienced the American Revolution as a liberating event that burst the shackles of colonial-era repression. In America, disestablishment meant release from the obligation to support Protestant ministers, the flowering of religious liberty seemed to presage and accelerate the Church’s growth, and republican politics in temporal affairs seemed perfectly compatible with ecclesial monarchy.

American Catholic elites found French radicalism a useful foil to contrast with their own revolutionary inheritance, as they staked claims for Catholic participation in American public life. For example, in the eulogy that Bishop John Carroll of Baltimore delivered on the death of George Washington, Carroll lamented that if “the leaders of the [revolution] through which unhappy France has passed . . . [had] been influenced by a morality as pure and enlightened as that of Washington, . . . what scenes of carnage and cruelty . . . would have been spared . . . that ill-fated country? And how sacred and venerable would . . . still remain [its] sanctuaries of religion?”

This moral clarity, by which America’s Catholic leaders distinguished between a “good” American Revolution that fostered religious liberty for their faith and the “bad” French Revolution that suppressed it, proved eminently useful and durable. It gave them a ready response to anti-Catholic bigots at home and intransigent Catholic reactionaries abroad. And for good measure, it offered clerical elites a vocabulary to rebuke the supposedly “Jacobinical” attempts of the laity to “democratize” the Church and challenge their authority.

But the influence of the French Revolution extended beyond these effects, and the rise of an American Catholic “church of immigrants” is a clear-cut example:

In the 1790s—decades before mass immigration from Ireland or Germany—Catholic churches across the United States were filled with refugees escaping the escalating anticlerical violence and political radicalism of the French Revolution, as well as many others fleeing the successful slave insurrection in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (proclaimed independent Haiti in 1804).

Many American parishes, and eventually new dioceses, were led by French clergy. Together with later French immigrant priests and nuns recruited to the “American missions,” these refugees founded Catholic schools, seminaries, and convents, especially throughout a western frontier secured for the United States by the Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812 (events that were themselves products of French Revolutionary warfare).

In 1791, French priests of the Society of Saint-Sulpice founded the country’s first Catholic seminary in Baltimore. Some 50 years later, the French immigrant priest Édouard Sorin founded the University of Notre Dame under the auspices of the bishop of Vincennes—himself a native of France.

Later immigrants arriving from across Catholic Europe would come into an American Church that refugees from the French Revolution were doing much to build. Conflict and collaboration between these newer arrivals and their French predecessors would help define parish and diocesan life through the first half of the 19th century.

Thanks to scholars like Annabelle Melville, Christopher Kauffman, Michael Pasquier, and Gabrielle Guillerm, the vital work of these French immigrants is familiar to historians of American Catholicism. And in my dissertation, I focus on how this pronounced French presence could be a double-edged sword for the American Church.

“The Propagation Society.___More Free Than Welcome,” print by Nathaniel

Currier, 1855. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division,

Washington, D.C. Illustrated for the esteemed New York printer Nathaniel

Currier (who later formed one half of Currier & Ives), this cartoon typifies the

fearmongering that motivated anti-Catholic animus in the antebellum United

States. Portraying the France-based Society for the Propagation of the

Faith as fomenting a Papal conspiracy to invade America and subvert its

free institutions, it depicts “Young America” and “Brother Jonathan” holding

the line against an onslaught of European prelates and Pope Pius IX,

thwarting their efforts to “put the ‘Mark of the Beast’ on Americans.”

Amid a French Revolution that troubled a broad swath of American observers, French Catholic immigrants had been easily cast as sympathetic victims of the Jacobins. But as a conservative reaction—which saw the restoration of a stridently Catholic monarchy in France—rippled across the post-revolutionary Atlantic, anti-Catholic polemicists increasingly saw French priests as a dangerous fifth column. They were, in the words of Samuel F. B. Morse, part of a “foreign conspiracy against the liberties of the United States,” aimed at overthrowing the “American nursery of . . . the revolutionary school of France.”

Though an active Catholic conspiracy was a specter formed of nativist bigotry, many French Catholic immigrants did hold real affection for the Bourbon monarchy of the old regime—and gladly supported its post-revolutionary restoration. This latent monarchism tended to anger Catholic laypeople perhaps more than the general public, as Bishop William Dubourg of New Orleans noted in 1814, after news had spread that the monarchy was returning to France: “to be a well wisher to the Cause of the Bourbons is here a crime of the blackest dye.”

French clerics like Dubourg, whose royalist sympathies were well known, could attract the animosity of American Catholics intent on demonstrating their republican bona fides. However, most French immigrants took pains to reconcile their royalism with their loyalty to the United States. Perhaps none squared this circle as succinctly—or honestly—as did the Reverend Simon Bruté, who appealed to a “second French nature” to explain his insoluble political affinities. The arrival of figures like Bruté infused existing American Catholic antipathies toward the French Revolution with a vitriol born of personal experience, while their intellectual efforts helped to shape a Catholic politics in America that was distinctive within the Catholic world.

To my mind, then, by forging robust ties between a growing American Church and Catholic institutions across Europe, the French Revolution did much to produce the defining problem facing Catholics in 19th-century America: how to benefit from the contributions of Catholic immigrants—and from the links to Catholic Europe that their presence enhanced—while also downplaying uncomfortable ties to Europe’s resurgent Catholic monarchies and even to an increasingly anti-liberal Papacy.

I see this dilemma as the through-line connecting a whole host of issues central to our story about American Catholicism: parish-level fights among French and Irish immigrants in the port cities of the early republic; contests between parish trustees and their bishops; the influence of the restored Jesuits; the rise of an enthusiastic American ultramontanism; nativist invectives against “political Romanism” and the Catholic apologias marshaled in response; and how events like the Revolutions of 1848, Italian Risorgimento, and the First Vatican Council galvanized American Catholics, while further alienating them from their Protestant neighbors.

In tracing the French Revolution’s profound and enduring consequences for such issues, I hope to point scholars toward a new narrative of American Catholicism—one that highlights the broad intellectual and institutional continuities shaping the American Church as it grew from an embattled minority religion to an energetic presence within the 19th-century United States.

PC: Tell us how you arrived at this topic.

MO: I wrote a master’s thesis at the University of South Carolina on a woman whose aristocratic French family sent her to the United States at the height of the Reign of Terror. Only eleven years old when she arrived in New York in 1794, Natalie Delage eventually married into a prominent South Carolina family (much to her French family’s chagrin), and spent most of the rest of her life in the American South. Although the Church had no institutional presence in the midlands of South Carolina where she settled, she remained a devout Catholic and sought to raise her children in her faith.

Natalie’s faith also connected her to coreligionists and Catholic institutions across the country and the Atlantic world. She knew Charleston’s Bishop John England fairly well. She had her sons educated at Mount St. Mary’s College in Emmitsburg, Maryland, founded by the French immigrant priest John Dubois (the future bishop of New York). Her faith also helped sustain her ties to family still in France, despite the difficulties of distance and their increasingly divergent political commitments. Her story is pretty wild, and you can read it here.

Writing about Natalie allowed me to explore in miniature the main themes I develop in my dissertation. Above all, it helped me to see Catholicism in 19th-century America from the perspective of a wider Catholic world shaped far more by the French Revolution than by anything happening in the United States.

The point of this perspective isn’t to imagine Catholics in the United States in lock step with Rome—or Paris—or Vienna. Rather, it is to recognize that as Catholic Americans grafted their faith into the fabric of America’s republican culture and institutions, they did so as part of a Catholic world being remade by revolutionary forces—which for most Catholics, especially among the elite, was epitomized far more by events in France than in America.

PC: You worked a great deal in the Propaganda Fide Records. Tell us about the strengths of this collection.

MO: The Propaganda Fide Records are something of a rite of passage for scholars of Catholicism in early America!

152 reels of microfilm, drawn from the archives of the Holy See’s office directing Church affairs in “missionary territories,” and focused on its dealings with North America—this collection contains multitudes.

And while a recent book written by Matteo Binasco and edited by Kathleen Cummings attests to the incredible variety of American sources in Roman archives, the Propaganda Fide Records are still the first place that any U.S.-based scholar should go to explore how American Catholics fit within a wider Catholic world, whose leadership considered the 19th-century United States a far-flung missionary field.

Because the collection consists of the Propaganda Fide’s interventions in a wide variety of issues—parochial disputes, episcopal succession, diocesan expansion, missionary recruitment, and the establishment of seminaries, convents, and monastic houses, to name but a few—these records shed light on a great deal of topics at the heart of my dissertation.

What’s more, because Propaganda Fide relied on written reports and other supporting documents from interested American parties, these records are a surprisingly rich source for things like pamphlets, newspapers, and other rare documents, in addition to letters from America’s Catholic elites seeking to frame their experience to a distant Holy See.

I did spend dozens of hours with this collection last year and only scratched the surface. That’s not only because of its incredible vastness, but also because these documents are in Latin, Italian, Spanish, and German, along with the French and English that I read well. But before future researchers despair, there is an extremely useful multivolume calendar with item-level descriptions (see the work of Finbar Kenneally, Anton Debevec, and Luca Codignola), Notre Dame’s archivists are incredibly helpful navigators, and I’m happy to field further questions about it, too!

PC: Your research explores how the French Revolution shaped American Catholicism but also how American Catholics participated in the events in France. Is there a story that best embodies this important dynamic?

MO: Absolutely, one example that immediately springs to mind is Americans’ role in promoting French foreign missions in the aftermath of the Revolution.

One of the immediate consequences of the French Revolution was that a Catholic revival swept France and much of Europe in its wake. This revival saw seminaries and colleges rebuilt, old religious orders restored and new ones founded, and—especially consequential for the American Church—a marked increase in Catholic missionary activity abroad.

In a story that previous Cushwa grant recipient Gabrielle Guillerm explores in great detail, American Catholics seized on this missionary enthusiasm, taking extended voyages across the Atlantic to plead for aid; and, in the words of Bishop William Dubourg of New Orleans, to “ransack all of Catholic Europe” for willing recruits.

While Americans of all backgrounds took these trips, French immigrants like Dubourg were often best positioned to marshal personal connections to the Catholic elite of Europe. And not only clergy: Natalie Delage and her children also visited France to see her family around this time. During an audience with the king, Natalie secured a sizable royal donation to Mount St. Mary’s Seminary, where her sons were educated.

These channels were given institutional form with the establishment of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith in 1822, thanks in part to the encouragement of Bishop Dubourg. Throughout the 19th century, the Society contributed tens of thousands of Francs a year to Catholic institutions in America, through donations from individual Catholics, Church tithes, and royal largesse, while also encouraging the immigration of French missionary priests and women religious.

From the Bourbon Restoration through the American Civil War, the Society sent millions of dollars, works of art, and objects for religious worship to the United States, while it, and similar organizations in Austria, Bavaria, and Ireland, coordinated the immigration of hundreds of Catholic clergymen to work in the American missions. One French historian has termed this the “Marshall Plan of French Catholic aid to the American church.”

Portrait of King Louis-Philippe imposing a Cardinal’s Beretta on Archbishop

John Cheverus of Bordeaux in 1836, by François Marius Granet. Musée des

Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. Painted by one of the king’s favorite

artists, the scene reflects Granet’s characteristic interest in depicting the

grandeur of ecclesial architecture and the majesty of religious ritual. But it also

idealizes the supposed harmony between the Catholic Church and the French

monarchy that troubled Catholics and Protestants alike in 19th-century

America.

And though these efforts explain the continued French Catholic presence in 19th-century America, the close of the Revolutionary Era also allowed for former refugees to return home. In 1823, Bishop John Cheverus of Boston was called to head the French diocese of Montauban. The nomination sent shockwaves across the still overwhelmingly Protestant city, provoking a petition to the French government signed by over 200 of Boston’s leading citizens that Cheverus’s name be withdrawn. When Cheverus was later named Archbishop of Bordeaux in 1826, his successor at Montauban was New Orleans’ Bishop Dubourg—who gladly accepted the opportunity to leave a city that offered him none of the affection that Boston gave Cheverus.

The return migration of figures like Cheverus and Dubourg might seem an insignificant trickle compared to those arriving yearly from Europe. However, that these well-known former refugees now held high-status positions in the Church of the restored French monarchy gave anti-Catholic polemicists seemingly compelling evidence of Samuel Morse’s “foreign conspiracy.”

PC: Tell us about your favorite source you found in the archives this trip.

MO: I am always drawn to the letters of Simon Bruté, a figure whose importance to American Catholicism extends even beyond his lofty reputation as a seminary professor and frontier bishop.

Born in France in 1779, Bruté came of age amid the French Revolution, studied for the priesthood after Napoleon reopened the seminaries, and was recruited to America in 1810 by fellow Frenchman Bishop Benedict Flaget of Bardstown, Kentucky (the country’s first episcopal see west of the Alleghenies).

Bruté became an esteemed professor of theology, first at Saint Mary’s in Baltimore and then at Mount St. Mary’s in Emmitsburg, where he remained for most of his career. In 1834, a 55-year-old Bruté was appointed bishop of the newly erected diocese of Vincennes, Indiana, where he died five years later.

Throughout his long tenure at Mount St. Mary’s, Bruté was a much-beloved confidant, confessor, teacher, and friend to a wide array of individuals far more familiar than he to students of American Catholicism. Alongside Mount St. Mary’s founder Father John Dubois—who was made bishop of New York in 1826—Bruté helped train a generation of leading American churchmen, including future archbishops of New York John Hughes and John McCloskey. He also served as spiritual director for Mother Elizabeth Ann Seton to her death in 1821.

During his years at “The Mount,” Bruté developed relationships with leading Catholics across the United States. On the arrival of Bishop John England to Charleston in 1820, Bruté quickly became his frequent interlocutor, as well as an occasional contributor to Bishop England’s U.S. Catholic Miscellany—the country’s first Catholic newspaper.

He likewise carried on a lively correspondence with the North Carolina jurist William Gaston. A lawyer, U.S. Representative, and eventually a justice of his state’s supreme court, Gaston was perhaps the country’s most prominent Catholic politician in the early 19th century. Introduced when Gaston sent his daughters to Mother Seton’s school, Bruté and Gaston corresponded regularly from the late 1810s to Bruté’s death. The Diocese of Charleston Collection at Notre Dame holds over 150 of Bruté’s letters to “mon cher Gaston.”

Given Bruté’s extensive connections to Catholics across America and throughout the Atlantic world, he was a superlative source of information for the leaders of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, when it began its work in the 1820s.

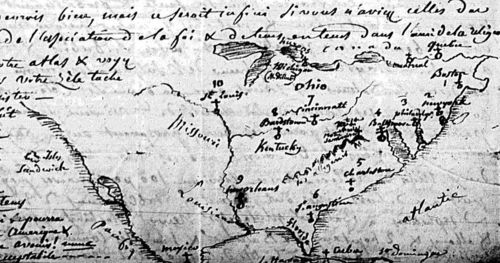

Society for the Propagation of the Faith Records (PFP), Lyon-Fribourg

Microfilm, Reel 5, Archives of the University of Notre Dame.

The document I’ve highlighted—an 1828 letter from Bruté to the Rev. Joseph Gignoux in Bordeaux—comes from the Society’s microfilmed records found at Notre Dame, and exhibits some of Bruté’s characteristically vivid style.

In densely packed prose and expansive rhetorical flourishes, Bruté thanked his “good friend of over twenty years” for a shipment of religious objects that had recently arrived in Maryland. This included books, two porcelain images of the Virgin, and two crucifixes, which were “relics that I have long searched for and nearly despaired of finding.” Bruté spent most of his letter giving details on the Church’s progress in America, and how the Society’s contributions were helping to advance the Catholic faith.

What I find especially charming—and what I’ve featured in this excerpt—is that Bruté’s letters are brimming with delightful sketches and drawings. These are often mere doodles: hearts, crosses, birds, flowers and the like. But in this case, Bruté had a more didactic intention. This map, he told Father Gignoux, was meant to illustrate both the prodigious growth of Catholicism in America, but also its great need: “Oh, if we could fully convince all Europe of the extreme importance of doing all that one might for this America!”

Bruté’s drawing neatly marks out the extent of the American Church by the late 1820s. What had been a single, extensive Diocese of Baltimore in 1790 now numbered ten dioceses stretching from Boston to St. Louis. And though this map—as with Bruté’s letter—centers on the Church in his adopted country, it is framed within a Catholic world extending from St. Domingue to the Sandwich Isles (that is, from Haiti to Hawaii) and from Mexico to Quebec. “Take out your atlas,” he instructed his friend, “and see the country that your zeal has touched.”

Peter Cajka is a visiting assistant teaching professor in the Department of American Studies at the University of Notre Dame.