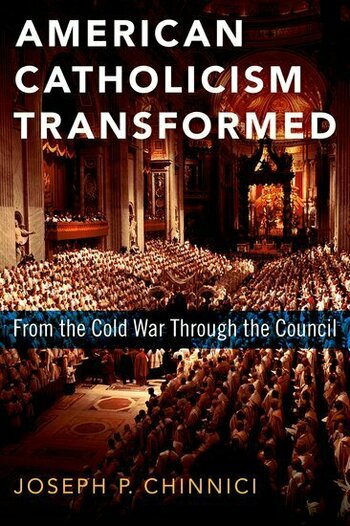

Joseph P. Chinnici, O.F.M., is the president emeritus of the Franciscan School of Theology and a longtime professor of church history. He served as president of the American Catholic Historical Association (2007–2008), and he was provincial minister of the Franciscan Friars of the St. Barbara Province (1988–1997). An Oxford-trained historian, Father Chinnici is widely published including Living Stones: The History and Structure of Catholic Spiritual Life in the United States (1989), When Values Collide: The Catholic Church, Sexual Abuse, and the Challenges of Leadership (2013), and Prayer and Practice in the American Catholic Community (2000) with Angelyn Dries, O.S.F. In early 2022, Jeffrey Burns (University of San Diego) corresponded with Father Chinnici about his most recent book, an important new study of the United States and the Second Vatican Council, American Catholicism Transformed: From the Cold War Through the Council (Oxford, 2021).

Jeffrey Burns: Much of your previous work examines spirituality and its historical development in the U.S. Church. This book is much grander in scope and content. How did you come to write it?

Joseph Chinnici: I was inspired by the current state of the Church. Even though the Second Vatican Council is now entrenched in many of the Church’s practices, its vision of the world and Catholic identity has all but been forgotten. This has occurred on several levels, both experiential and academic. Experientially, the public Church and society have been taken over to a large extent by political advocacy, networking, and monied interests. Official public documents rarely refer to conciliar teaching. For over nine years I was in a position of leadership with the Franciscans in the United States, attended episcopal meetings as a representative of religious men for three years, dealt as best I could with the abuse crisis, and witnessed many subtle changes in the profile of parish life in the American Catholic community as it entered into the culture wars that currently mark our social divisions. Academically, as an historian and a priest who had been formed in the immediate wake of the Council, I observed the changes and noted how they either departed from or reinforced what was understood to be the vision of the Council at that time. There had been no study of American participation at the Council since Vincent Yzermans in 1967 compiled the speeches given by the bishops of the United States. I wanted to make a contribution to our understanding of the Church. It has been a long-held conviction of mine that historians have been forgotten as public resources for the Church today. I believe the Second Vatican Council is still relevant to our present situation, if we would but pick up its major themes and insights. But first, we have to recover its memory.

JB: This seems to be a very personal work. To what extent did your personal experience shape the book?

JC: A great deal. No historian can divorce his or her own questions from the course of his personal life.

I was born in 1945 and spent my formative years enmeshed in Cold War Catholicism: Soviet-American tensions, the nuclear arms race, duck and cover drills where I hid under my school desk to keep from being obliterated by the Soviet attack. Images of Bishop Sheen and The Bells of St. Mary’s held powerful sway in our Catholic imagination. I was deeply immersed in the Catholic and American worlds which included common beliefs surrounding family life, male over female, white over black, Catholic truth over Protestant errors, a contained sexual morality, and a belief in “natural law” with the canonical precepts of the hierarchical Church holding sway. At the same time, commitment to the American way of life encouraged the assimilation of human rights language, participative governance, racial equality, and an incipient women’s movement. Renewal movements in theology, liturgy, scripture, religious life, and lay participation bubbled up from below. External threats of communism and secularism kept a highly explosive mix bottled up. I knew these ambiguities in the Church of the Cold War from my own experience, but I did not know how they developed nor how they fit together.

During college, I read all of the Vatican II documents as the external threat of the Cold War gave way to a politics of détente. One of the keys of my work is chapter four on the civil rights movement and its “appeal to conscience” as dissolving the inherited linkage behind divine, natural, and positive law that made both African Americans and women in both church and state inferior. In 1968 I moved along with our theologate from the closed seminary atmosphere of Santa Barbara to the wide open and raucous world of Berkeley. I studied for the priesthood at the Graduate Theological Union and learned from many Protestant ministers who had shaped the ecumenical movement. The social embeddedness of theology became a self-evident truth—how we explained our faith was shaped by what was happening on the street. The vision of Vatican II in Lumen Gentium, Dei Verbum, Sacrosanctum Concilium, Gaudium et Spes, and Unitatis Redintegratio took on real flesh in first-class professors of theology and society.

I returned from graduate studies at Oxford University in 1975 just as the Vietnam War was ending. The society and Church were changing. Anita Bryant’s attack on gay liberation; Phyllis Schlafly’s counter-gathering to the National Women’s Conference of 1977; an increasingly militant Catholic opposition to Roe v. Wade; the birth of the evangelical right and its subsequent alliance with affinity Catholics were all “signs of the times.” Then in the 1980s, these rivulets of religious and social reaction joined with the second phase of the Cold War and battled with the forces of conciliar change. Détente was over; a new Cold War emerged. John Paul II’s teaching in continuity with the Council bifurcated, his social thought picked up by the left, his moral teaching prized by the right. The Council became cherry-picked. On the part of some, public Catholic identity began to be narrowed into opposition to the replacements for anti-communism: secularism, feminism, liberalism, and relativism. On the part of others, another vision aligned itself with the social movements of the 1960s. Middle positions privileging the unique Catholic identity that balanced contraries became hollowed out. Interpretations of the Council and the conciliar generation itself battled for ascendancy and public power. Something was being lost and needed to be found. After a time in administration, I went looking. How could I get behind the culture wars to the historical record of what the Council had achieved?

JB: So how did you “get behind” or beyond the culture wars? How did you pursue your research?

JC: Oxford had taught me the importance of archival work, and I realized that to examine the Council and its American participation I needed primary sources—only the real record of the participants could cut through the ideological presuppositions about the past. The book really is a product of contact with bishops that had developed during my years in administration— Archbishop Quinn, Archbishop Weakland, Bishop Cummins, Cardinal Wuerl—and with archivists at Notre Dame, Baltimore, Duquesne, the Catholic University of America, and the Archdiocese of San Francisco. I am so dependent on all of these people and others for opening up the resources to me. The “resources” were twofold. First, I began by examining the archival records for the development of the postconciliar Church. A certain orientation emerged that would influence the structure of this volume. Second, the actual participants, bishops and theologians, who shaped the American experience at Vatican II focused my attention on the period 1940 to 1965. When I say I looked at all these papers, I mean to say it took almost 15 years of research, 10 years of writing, and a review of perhaps 10,000 manuscript pages. If you want to know how all the lives of the American conciliar generation intersected to help create the most important religious event of the 20th century, read the book.

JB: Short of reading the book, what are the main lessons you hope people take away?

JC: Based on my postconciliar research, two major themes needed explanation as to their origins: globalization and politicization. The archival information in the 1970s and 1980s gave abundant evidence that many developments in the Church in the United States needed to be interpreted from a global perspective. Issues that arose within our local church in the two decades after the Council were perceived both by Rome and other local churches as having implications for the world Church. To interpret them as local conflicts between the Church in the United States and Roman authorities anxious to clamp down on change was to fall prey to the approach of the popular press. The archives revealed something different. Issues such as women in ministry, the garb of American sisters, reception of communion in the hand, the sequencing of first communion/first confession, approaches to nuclear war, the critique of capitalism, the authority of national conferences, pastoral practices related to the divorced and separated, etc.—all of these issues garnered the attention not just of Rome but of other local churches who sensed a new type of American religious colonialism. Rome was simply in this sense the administrative center for the trends and complaints in local churches throughout the world. What were the origins of this massive shift in the influence of the Church in the United States from being the receptor of European immigration to becoming an important global player on the world stage? The historiographical implications were huge. The paradigm of an immigrant Church had diminished its public clout long before the Council began.

Second, politicization. The postconciliar archives produced a whole new sub-discipline valuable to historical interpretation: political science. We know that right after the Council, various groups in the Church at the grassroots level began to mirror the strategies and actions connected initially with the civil rights movement. This was only the beginning. Priests, religious, laity, newspapers, and professional associations received by osmosis into their practice the efficacy of direct action protest, symbolic gestures that upset the status quo, public pressure groupings of advocacy, a turn to “rights” as the operative category of social construction, the formation of “think tanks” and institutional centers supportive of positions on the right and the left, petitions published in prominent newspapers and orchestrated by newly constituted groupings of affinity adherents, direct mailing, small-group networking, personal alliances with the ecclesiastically powerful, a politics of negation designed to discredit those supporting another view, and the solicitation of monied supporters. This trend, only a seedling in the early 1960s, grew exponentially by the mid-1970s. I asked myself: What developments had set the stage for this particular entanglement between the Church and the American political process? There had been hints of the different moral and political languages present in the previous work of John McGreevy, Mark Massa, and Leslie Woodcock Tentler. In fact, the crossover between ecclesiology and the American political experiment had begun with World War II and was directly related to the geopolitical stance of the papacy and the political culture at large in its struggle against communism. The Catholicism of the 1950s was not simply a “ghetto Catholicism.”

JB: Besides redefining the contours of preconciliar Catholicism, one of the most important contributions your study makes is to take seriously the role of U.S. bishops and theologians at the Council. Popular accounts generally limit American influence to the work of John Courtney Murray, S.J., and religious liberty, but the background you lay out suggests U.S. bishops and theologians were bringing a distinct experience of church. What was the role of the U.S. bishops and theologians at the Council?

JC: Contrary to the common opinion, the American bishops were actively engaged in the Council. Through the archival collections, I had first-hand access to those who shaped the Council from the American side: John Dearden, John Wright, Ernest Primeau, Charles Helmsing, Paul Hallinan, cardinals Meyer, Ritter, Spellman, and McIntyre, and others. For many participants the Council changed their lives. I am hoping that current readers of this book may take courage from the changes U.S. bishops underwent. In addition, a host of theologians, both religious and diocesan, made significant contributions to the understanding of the liturgy, collegiality, the Church, scripture and tradition, and ecumenism. Recovering the voices of Thomas Stransky, Frederick McManus, Godfrey Diekmann, Thomas William Coyle, George Higgins, and Barnabas Ahern moves our analysis forward beyond simply the stellar work of John Courtney Murray. In fact the vision of the United States hierarchy, its acceptance of the major thrusts of the Council, and the collaborative work of the theologians hold up a clear and critical standard for the hierarchical and intellectual leadership of the Church today and the divisive polarizations marking Catholicism.

JB: Concern for contemporary divisions in the Church has become all-consuming, but your study suggests we need to place these divisions in a larger context.

JC: As I try to show in my book, the contemporary debates and struggles in the Church are not new, either in content or in intensity. They are simply more democratized through the political processes described above. Yet the basic divisions date from World War II and the impact of the Cold War. The unified 1950s are a convenient myth of consolation; the Council as a rupture from the past is a chimera. Much more enlivening is the drama of history, how the Church at all times is culturally embedded, how it deals with both unity and diversity together, how the law of continuity and the law of change live in a dialectical relationship with each other. And how this balance requires ecclesial allegiance, creativity, and a certain ascetical discipline. The work tries to illuminate how change happens in the Church, the importance of remaining communally rooted, and the patience it takes for organic development.

The different postures we associate with our divisions today—most recently manifest in the recent episcopal arguments over communion and the stances taken in pro-life positions—reflect fissures present in the community for the last 70 years. Two simple examples. The struggle at the Council was between divergent visions of what it means to be “pastoral”: Does “pastoral” refer to the duty of the hierarchy to teach the truth or is “being pastoral” the duty of the whole Church to teach its inner communal truth as it touches both the objective inheritance and the subjective experiences and difficulties of a people on pilgrimage to the fullness of truth? The struggle at the Council was between two strands of Catholicity: Is Catholicity in a pluralistic and secular society to be determined in large part by seeing the Church in its liturgy, its doctrine, its practice, as a citadel against enemies? Or is one’s Catholicity in a pluralistic and secular world to be understood as an ecclesial faith “gathering up into wholeness and fulfillment” the truths already present in the world? If in the short run a Cold War mentality and practice seem ascendant right now, they do so at the cost of a betrayal of the historical record of what happened since World War II. Perhaps the divergent definitions of “pastoral” and “Catholicity” need each other. Catholicism is a system of contraries, not contradictories.

JB: Any final thoughts?

JC: One of the difficulties facing the historian of Catholicism after the Council is to comprehend that the Council was a religious event touching the life of faith. All of its participants were believers trying to express what they considered to be the movements of the Holy Spirit both personally and collectively. The participants gathered together not as politicians—although as the book indicates there were plenty of political elements; nor did they gather as sociologists—although there is some evidence of a religious “effervescence” operative; nor as ideologues, although there are indications certainly of strongly held theological and social convictions; nor simply as representatives of a particular national identity—although despite the “internationalism” that leaps from the pages of the archival record the “American” contribution is often mistakenly narrowed to religious freedom. They gathered together, bishops and theologians, Catholics and Protestants, clerics and laity, as believers: they talked, they prayed, they listened, they disagreed; they ate together and they took breaks together; all of them labored extensively to reach positions they considered to be helpful for the Body of Christ in the modern era. They suffered from the limitations of gender and training. But what they achieved cannot be understood unless the contemporary discipline of history takes seriously their religious convictions expressed in theological and ecclesial terminology. For myself, I approach the study of history with the presuppositions of the Franciscan spiritual, theological, and social tradition. I am hopeful that the work makes some contribution to a revival of the Council’s vision of a Catholic and ecclesial faith and its relationship to the world of our times.

Jeffrey Burns is the director of the Frances G. Harpst Center for Catholic Thought and Culture at the University of San Diego and the director of the Academy of American Franciscan History.

This interview appears in the spring 2022 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.