International Bridge between El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Undated. Courtesy of the El Paso Public Library (Southwest Collection).

International Bridge between El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Undated. Courtesy of the El Paso Public Library (Southwest Collection).

In recent years, debates about the U.S.-Mexico border have dominated news headlines. These debates reached a fever pitch when the Department of Homeland Security began separating families who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border without proper documentation in the spring of 2018. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Catholic Charities, and Catholic Social Services immediately protested the separation of families at the border. The bishops called for the Trump administration to end family separation and child detention. Catholic Charities and Catholic Social Services sent numerous volunteers to help with the crisis.

Both of those agencies were well-equipped to provide advocacy services to families seeking to enter the United States and those impacted by the zero-tolerance policy of 2018. This is largely because Catholic agencies have been providing such services at the border for nearly a century. Catholic advocacy at the U.S.-Mexico border has long focused on family unification and resistance to immigration policies that target racial minorities for removal. This legacy makes Catholic agencies uniquely positioned to assist vulnerable immigrants.

Before continuing, it is worth making a quick note about terminology. In this piece, “Mexican” refers to an individual with Mexican citizenship, while “Mexican American” refers to a U.S. citizen of Mexican-descent. “Mexican-descent community,” or “people of Mexican-descent” is a way of referencing a community with mixed citizenship status. It is important to make these distinctions because for many years, individuals have used the term Mexican as a catchall to imply that Mexican Americans are not American.

It Happened Once Before

Staff at the Border Office of the National Catholic Welfare Conference. Courtesy of the C. L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department, University of Texas at El Paso.

Staff at the Border Office of the National Catholic Welfare Conference. Courtesy of the C. L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department, University of Texas at El Paso.

The Catholic Church has been working with immigrants at the U.S.-Mexico border since the 1920s, when the National Catholic Welfare Conference (an earlier incarnation of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops), established an immigration office in El Paso, Texas. Throughout much of the 20th century, El Paso was the “gateway” between the United States and Mexico. It was the largest city between Denver, Los Angeles, San Antonio, and Mexico City, where all the major railroads converged. The Church’s immigration office was designed to assist those crossing the border, most of whom were Catholic. The office was small, staffed by a director, a few case workers, and an administrative assistant. But by the time the office closed in 1967, it had processed some 1.75 million family cases.

Perhaps the most important episode of Catholic advocacy at the southern border took place during the Great Depression. Popularly, we remember the Depression as a difficult moment in U.S. history. Families lost their homes and many people faced financial ruin and starvation. Images of the Dust Bowl, Okies, or Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” predominate. We talk about the period as a moment of solidarity. But the Great Depression had other dimensions as well. Between 1929 and 1939, an estimated 400,000 to 2,000,000 Mexicans and Mexican Americans were expelled from the United States.

Historians are not sure exactly how many people were forced out of the U.S. during the Depression. Both U.S. and Mexican officials kept fairly inconsistent records during the period. Figures vary dramatically by scholar and source. The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights estimated in 1980 that federal officials expelled approximately 500,000 people of Mexican-descent, over half of whom held U.S. citizenship. The state of California issued a bill of apology in 2006, noting that “In California alone, approximately 400,000 American citizens and legal residents of Mexican ancestry were forced to go to Mexico.” These numbers were based largely on research conducted by historians Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, who argue that close to 2 million Mexicans and Mexican Americans were expelled from the United States between 1929 and 1939. Other historians suggest that the total number of people expelled is closer to 400,000. The N.C.W.C.’s figures suggest that close to 500,000 people passed through El Paso - over 80 percent of whom were U.S. citizens or permanent residents - as a result of repatriation.i

As the world sunk into deep economic stagnation in the 1930s, welfare agencies throughout the United States began relocating Mexicans and Mexican Americans to Mexico. To justify their actions, welfare agents appealed to racialized stereotypes of Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans as diseased and un-American. Newspapers reported these mass departures in celebratory tones. Many believed that Mexican-descent workers took jobs from deserving white Americans.

Throughout most of the 1930s, welfare agencies across the nation, including a Catholic Charities office in Los Angeles, applauded efforts to remove people of Mexican-descent. Many refused to register Mexican or Mexican American clients on their rolls. Instead, they offered transportation to Mexico. Other agencies invited immigration officials to welfare offices, encouraging them to investigate their clients’ immigration status. On the advice of welfare agents, immigration officers conducted raids in neighborhoods home to residents of Mexican-descent.

Historians often refer to the coordinated removal of Mexicans and Mexican Americans during the Depression as “Mexican repatriation.” Between 1929 and 1935 alone, the United States lost roughly one-fifth of its total Mexican-descent population. Countless families were torn apart. In some instances, U.S.-born children never saw or heard from their parents again. Mexican repatriation became one of the largest racial expulsions in U.S. history, second only to the American Indian campaigns of the 19th century.ii

Few groups protested the mass expulsion. Through the work of its border agent, Cleofás Calleros, the Catholic Church’s immigration office mounted the most significant resistance to repatriation. During the early 1930s, at the height of Mexican repatriation, Calleros traveled throughout the West and Southwest, speaking to local groups such as the Knights of Columbus and the National Council of Catholic Men. He warned that the damage caused by repatriation would discourage Mexican immigrants from seeking naturalization, tear families apart, worsen relations with Mexico, and cause generations of Americans to live in fear of the federal government.

Apostle of the Border

Cleofás Calleros. Courtesy of UTEP Special Collections.

Cleofás Calleros. Courtesy of UTEP Special Collections.

Known as “the Apostle of the Border,” Cleofás Calleros dedicated most of his life to working on behalf of Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. Calleros immigrated to the U.S. with his family at age six. He attended Sacred Heart Academy in El Paso and eventually earned a teaching certificate. In 1918, he joined the U.S. Army, and soon became a naturalized citizen. While serving in Germany, he was injured and received the Purple Heart. After the war, Calleros returned to El Paso and in short order married Benita Blanco. He spent much of his spare time volunteering at his local church. When the Catholic immigration office lost its director in 1926, the El Paso bishop recommended Calleros for the job. He would spend the next 41 years directing the El Paso office.iii

Calleros’ contemporaries described him as “stubborn” and “pushy,” but noted “there wasn’t anything mean about him.” The cantankerous border agent drew upon his personal experience and devout Catholicism to aid his work. His own successful immigration experience made him a champion to poor immigrants. With Calleros’ help, more than 30,000 individuals gained citizenship. When immigration officials attempted to separate children from their parents, Calleros’ famous temper flared. On more than one occasion, he stormed into immigration headquarters, demanding that families remain unified. More often than not, immigration officials gave way to Calleros’ insistence.iv

In truth, Calleros’ efforts met with heartbreak and failure more often than success, as in the case of Angela Hernández de Sánchez. After a week of visiting family in Carrizal, Chihuahua, Hernández was anxious to return home to her three children in El Paso. She began crossing the bridge between El Paso and Juárez and then paused, the echo of her footsteps growing silent. She turned and watched a line of cars moving in the opposite direction, weighed down with entire families and their belongings.

Dread filled the young mother. She tried to remind herself that she had no reason to worry. Despite recent rumors of many Texas and California families forced out of the United States, Hernández reassured herself that her situation was different. She was a legal U.S. resident. She had a job. Two of her children were U.S. citizens. For 15 years, Hernández had visited family in Mexico and returned to El Paso without incident.

That night was different. Instead of waving her through the checkpoint, U.S. immigration officers pulled Hernández aside. For the first time in 15 years, they demanded she turn over proof of residence and proper medical clearance. Crossing the border was a different experience in the 1930s than it is today. At the time, border agents rarely requested much in the way of documentation. When Hernández was unable to provide the requested documents, they arrested her.

The following day, a U.S. public health doctor subjected her to an invasive medical exam. Convinced that Hernández suffered from venereal disease, the doctor refused to issue medical clearance. He recommended that immigration officials immediately deport her. Later that day, immigration officials released the young woman into the custody of Calleros’ office.v

As Hernández awaited the results of the blood test that would prove she did not have a venereal disease, immigration officials drew up a warrant of deportation. Working with Calleros’ office, Hernández provided proof of her status as a U.S. resident and her children’s citizenship. Her efforts were to no avail. Cloaking his racism with the veneer of medical science, the examining doctor insisted that Hernández carried a undetectable strain of syphilis. Despite the clean blood test, he refused to issue clearance. She appealed the decision but immigration officials denied her request and issued a deportation warrant on March 12.

Calleros in front of La Misión de San Antonio de Ysleta del Sur in El Paso, Texas. Courtesy of UTEP Special Collections.

Calleros in front of La Misión de San Antonio de Ysleta del Sur in El Paso, Texas. Courtesy of UTEP Special Collections.

Sobbing and in a panic, Hernández begged Calleros and his supervisor to intervene. They reached out to contacts in Washington, but were unable to prevent her deportation. Six weeks after attempting to return home from what she believed was an ordinary family visit, immigration officials deported Hernández and her three children on charges that she was a menace to public health. Crying, Hernández crossed the border into Mexico.vi

Hernández and her three children were just four of an estimated 400,000 to 2,000,000 people of Mexican-descent expelled from the U.S. between 1929 and 1939. Her story is both remarkable in its extralegality—Hernández was a legal U.S. resident, not subject to deportation under any contemporary immigration law—and unremarkable in its common recurrence across the Southwest during the 1930s. Calleros would assist thousands of individuals in similar situations.

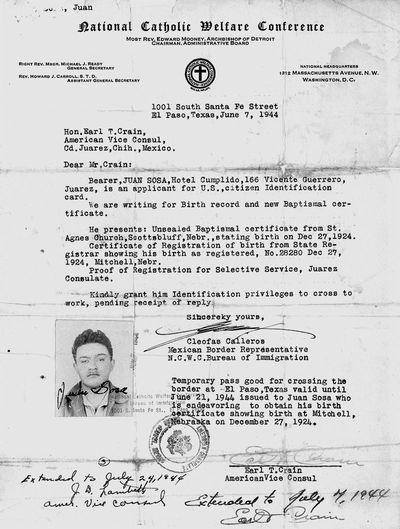

Not all of Calleros’ attempts to help ended in failure. In 1944, a young man named Juan Sosa arrived at the border. His family had fled the U.S. at the height of Mexican repatriation in 1931, when Sosa was seven years old. Thirteen years later, in 1944, he found a job in El Paso. When he attempted to enter the U.S., immigration officials detained him. Sosa was in fact at U.S. citizen, but like so many impoverished families in the 1930s, Sosa’s family had never applied for U.S. passports (a relatively new invention at the time) for their children. All that he had to prove his U.S. citizenship were the tattered remains of a baptismal certificate.

Juan Sosa’s identification letter. Courtesy of the Center for Migration Studies.

Juan Sosa’s identification letter. Courtesy of the Center for Migration Studies.

Calleros traced Sosa’s baptismal certificate to a church in Scottsbluff, Nebraska. At first, immigration officials threatened to remove Sosa from the country, but after careful negotiations, Calleros convinced them to allow Sosa to remain. Calleros issued an identification letter, which immigration officials then certified. This letter served as proof of Sosa’s U.S. citizenship, while he awaited his U.S. passport.vii

There are countless stories like Sosa’s. It is because of stories like these Cleofás Calleros remains one of the most important, though least known, Catholics to have fought for Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans during the 20th century. In addition to his work with immigrants, Calleros served on the boards of 14 charitable organizations. His advocacy during a dark chapter of American history serves to remind us of the deep history of Catholic activism at the border.

Later in his life, Calleros estimated that the United States had deported, repatriated, or otherwise expelled more than 750,000 Mexicans and Mexican Americans during Mexican repatriation. He estimated that more than 85 percent of those expelled during the 1930s held U.S. citizenship. In a speech to Catholic social workers in 1960, he remarked, “we [sent] people back to a country that was not their country, back to homes that they had never lived in, that had never existed ... because [they] had no jobs.”viii Calleros’ words are as stirring now as they were in 1960. Decades after his death, the El Paso community and numerous families remain indebted to Calleros, and many long-time El Pasoans remember his legacy today.

[i] Pablo Yankelevich and Kelly Lytle Hernández, “An Introduction to el Archivo Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Migración,” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 4, no. 1 (Spring 2009), 219–239; Paul Taylor, “Critique of the Official Statistics of Mexican Migration to and from the United States” in International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations, Walter F. Willcox, editor (Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Research, Government Printing Office, 1931), 581–590; Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton University Press, 2004); Ian Haney-López, White By Law: The Legal Construction of Race (New York University Press, 2006); Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (University of New Mexico Press, 2006); Camilla Guérin-Gonzales, Mexican Workers and American Dreams: Immigration, Repatriation, and California Farm Labor, 1900–1939 (Rutgers University Press, 1994); Abraham Hoffman, Unwanted Mexican Americans: Repatriation Pressures, 1929–1939 (Arizona University Press, 1976); Vicky Ruiz, “Nuestra América: Latino History as United States History, Journal of American History 93, no. 3 (2006), 655–728.

[ii] Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 75.

[iii] Bruce Mohler to Thomas Mulholland, April 11, 1929, Box 3, Cleofás Calleros Papers, University of Texas at El Paso; Cleofás Calleros to Bruce Mohler, June 29, 1926; Bruce Mohler to Father John Burke, July 10, 1926; Bruce Mohler to Thomas Mulholland, August 17, 1926, Box 16, Folder 162, CMS 023.

[iv] As quoted in Marjorie Sánchez-Walker, “Migration Quicksand: Immigration Law and Immigration Advocates at the El Paso-Ciudad Juárez Border Crossing, 1933–1941,” 28–29; Mario T. García, Católicos: Resistance and Affirmation in Chicano Catholic History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008), 59.

[v] Adenitis is a glandular swelling that physicians at the time typically associated with venereal disease. Prof. Dr. Franz Mracek, Atlas of Syphilis and the Venereal Diseases Including a Brief Treatise on the Pathology and Treatment (Philadelphia: WB Saunders & Company, 1900), 93.

[vi] As recounted in R. Reynolds McKay, “Texas Mexican Repatriation During the Great Depression” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Oklahoma, 1982), 98–100; Cleofás Calleros to Bruce Mohler, January 25, 1934, Box 14, no identifiable folder, Calleros Papers.

[vii] Cleofás Calleros to Bruce Mohler, July 28, 1944; Cleofás Calleros to Earl T. Crain, June 7, 1944, in folder: Mexican Border Documents in Use, Box 54, 023 CMS.

[viii] Cleofás Calleros, “New Mexican Immigrants Into the United States,” Box 6, Folder: BCSS, CMS 023.

Maggie Elmore is a postdoctoral research associate at the Cushwa Center.

This article appears in the spring 2019 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.