Do archives exist for the glory of the people whose records they preserve? Should archivists save what they find agreeable and destroy what they find disagreeable? After all, the victors write the history books, so why preserve records of the losers?

Historians may reject such ideas without a second thought, but the popular understanding of archives and historical collections often seems more in harmony with the 1973 Woody Allen movie Sleeper. In the film, Miles Monroe wakes up after 200 years of cryogenic sleep. Miles answers questions about strange artifacts from the late 20th century. Nothing about Richard Nixon has survived except a single clip from a television appearance. Who was this man? He must have done something terrible for all records of him to have been destroyed. Miles agrees with this interpretation.

An exhibit at Notre Dame inspired a graduate student to write an article in the February 1996 issue of the conservative student newspaper Right Reason. The exhibit showed the range of material in the Notre Dame Libraries’ Catholic Americana Collection. Both the Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN) and Catholics for a Free Choice (CFFC) appeared in the exhibit. The student had no objection to the inclusion of EWTN, but objected strongly to CFFC. In his article, “Catholics for a Free Choice Do Not Exist,” he explained that CFFC did not qualify as Catholic because it rejected Catholic teaching about abortion. It represented the opinion of one person, the founder, and had a membership of only a few hundred people. Near the end of the article, he reported that he had given the librarian in charge of the exhibit an opportunity to mend her ways, but she had failed to do so.

Should bishops refuse communion to Catholic Democrats who follow the party line on abortion? Can we even agree to call President Biden Catholic? We cannot agree. But we should nevertheless, whatever our opinions, recognize the importance of preserving records representing all sides of any controversy.

Consider the ambitions of a young Catholic who feels called to defend traditional views against dissenters. What would such a writer need to support his arguments? Could he make a convincing case by quoting others who agreed with him? Would the EWTN documents in the Catholic Americana Collection suffice? Or could he perhaps make a better case by studying the documents generated by the dissenters themselves?

The Notre Dame Archives, strictly defined, includes only the records of Notre Dame itself, which accumulate during the daily transaction of university business. If Notre Dame invites President Obama to speak at commencement, related documents will eventually come to the archives. This will not mean that everybody at Notre Dame approves of the invitation, and records of protests will also come to the archives.

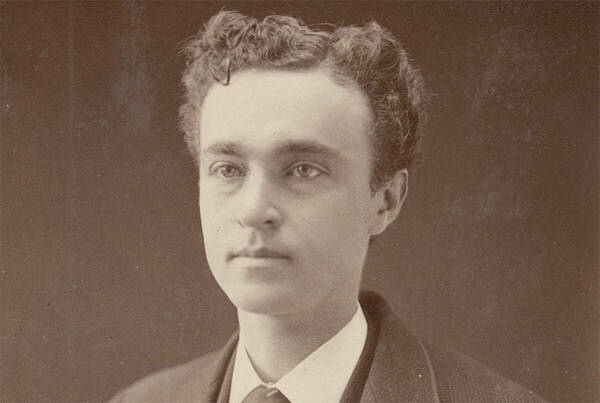

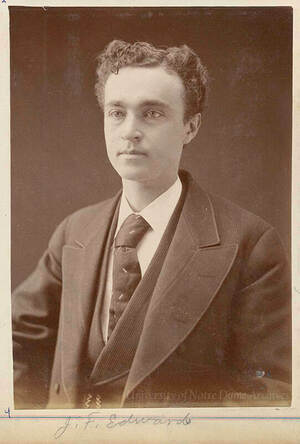

Beyond the strict definition, the archives at Notre Dame has for a century and a half collected and preserved records of Catholicism in the United States. In the 1870s, Notre Dame librarian and history professor James F. Edwards admired the early missionary bishops and began what he called the Catholic Archives of America to celebrate his heroes by collecting their correspondence. As a better understanding of archival collections developed, the archives came to represent a wide range of Catholic convictions, some of them extreme and no doubt questionable.

In fact, the archives has also preserved anti-Catholic documents along with Catholic rebuttals. The diversity of Catholic opinion undermines one anti-Catholic accusation: that Catholics don’t think for themselves, that they only believe what the pope tells them to believe.

In the Notre Dame Archives, you can find records of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, but also of Consortium Perfectae Caritatis; of the National Catholic Reporter and of Our Sunday Visitor. You can find papers of Father Richard McBrien, but also of Father Paul Marx; of Eugene Kennedy and Ralph McInerny; of Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., and Rose Eileen Masterman, C.S.C. Those who do research in the archives can weigh the evidence before they weigh in with their own interpretations.

In the Catholic Church as in the nation, we have trouble listening to people who disagree with us. We can engage in ecumenical dialog with people of other faiths, but not with Catholics of other opinions. The internet helps to foster the illusion that all right-thinking people agree and that we don’t need to hear from those who disagree. Search engines perpetuate this division by feeding us information in harmony with what we have chosen to read in the past and filtering out information that challenges our views. We have our information and they have theirs.

During the 20th century the word “information” acquired a golden halo. As digital computers developed and applications went beyond calculations to storage and retrieval of data, we began to call the associated discipline “information technology.” Library schools became schools of information science.

The Wikipedia article on information reveals that information reduces uncertainty. It includes a section on recordkeeping that repeats the traditional wisdom: records have value as information and as evidence. In court or in scholarly writings, records can settle disputed questions. But the recent glory of information tends to obscure the evidential value of records.

Archivists keep records that have ongoing importance for our cultural memory. With the popularity of digital images, a question arises as to whether we need to keep records in their original form. After all, the digital images of texts can yield, through optical character recognition, information far more useful once Google has gobbled it up. Why preserve the record itself when we have all the information we need in the digital version?

We can begin to answer this question with the help of television shows about crime scene investigation. In such shows, the criminal unwittingly leaves behind evidence that the crime scene investigators can discover as long as the scene remains intact. Photographs still have their role, but obviously can’t preserve all the evidence—the microscopic traces, DNA in the blood, blowfly larvae. The crime scene investigators and their colleagues in the labs proceed with absolute neutrality in their analysis of the evidence. The homicide detectives may have a favorite suspect, but evidence eventually identifies the real killer.

Images of documents preserve only a fraction of the evidence in the original. Leaving criminal tendencies aside for the moment, the technology to capture all the evidence in digital form does not exist. Visible characteristics don’t all come through, even with digital photography at the highest resolution. And, obviously, invisible characteristics don’t appear in digital images.

Imagine a 19th-century Holy Cross brother at Notre Dame keeping student accounts in huge ledger books. His pen sometimes skips, so that an 8 might look like a 6 or a 5 or a 3 in the digital image he never imagines. On paper, though, the pen makes enough of a scratch to eliminate uncertainty.

The ink in old documents can fade away. Ultraviolet or infrared light can sometimes make the writing legible again—but only if the original documents still exist. Who knows what other technology might make lost writing reappear in the future?

As a 21-year-old man in 1824, the disaffected Presbyterian Orestes Brownson kept a notebook in which he wrote observations that, a dozen years later, the Transcendentalist Orestes Brownson decided to obliterate with clippings from The Boston Reformer. In 1844 Brownson converted to Catholicism. His papers came to Notre Dame; the archives preserved the scrapbook and microfilmed the papers. Why not throw away the scrapbook? Archives always need more space. Instead the archivist, having preserved images of the clippings, removed them so as to make the writing underneath accessible again. (“What is worse than prejudice?” asked the young Brownson.)

A few paragraphs back we put criminal tendencies aside. But Catholic doctrine reminds us of the universal human tendency to sin. Some among us falsify records. The law allows police to lie in their pursuit of truth and justice. Governments make disinformation a tactical tool. Lately we have been reading news about fake news.

When uncertainty arises as to the authenticity of a record, it helps to have the original document and not a digital derivative. With techniques not unlike those in the television programs, experts can determine the age of paper and ink, analyze handwriting and detect forgeries. And the technology will improve as time goes by.

On September 6, 1866, James F. Edwards, age 18, registered at Notre Dame. On September 3, 1867, James F. Edwards, age 17, registered for another year. And on September 1, 1868, he registered again, having turned 18, apparently for the second time. These facts appear in Volume II of a series of ledgers known as “Student Daybooks.” If you go to the archives and look at the original records, you will discover, as I did, that the record for 1866 clearly says 18, not 16. Bad information, but nevertheless evidence—in this case evidence of human imperfection.

Those who generate records during the normal course of business intend to provide reliable information. But in this information, scholars in the future may see evidence of evils or of virtues that the recordkeepers never recognized. Catholic priests kept records of the slaves that they owned. The cause for canonization of any saint relies on routine records.

According to its website, “The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum is home to approximately 46 million pages of documents, and 3,700 hours of recorded Presidential conversations known as the ‘White House Tapes,’ 4,000 separate recordings of broadcast video, nearly 4,500 audio recordings, 300,000 still photographs, 2 million feet of film, and more than 35,000 State and Public Gifts.” Whatever we might think of President Nixon, we need to preserve the records of his administration.

Kevin Cawley retired in 2019 from his role as senior archivist and curator of manuscripts at the Archives of the University of Notre Dame, after 36 years of service.