Sarah Shortall is assistant professor of history at the University of Notre Dame, where her research and teaching concentrate on the intellectual and cultural history of modern Europe, with a particular interest in modern France, Catholic thought, and the relationship between religion and politics. Her book Soldiers of God in a Secular World: Catholic Theology and Twentieth-Century French Politics (Harvard, 2021) has won numerous awards, including the Laurence Wylie Prize in French Cultural Studies from New York University and the first place Book Award for History from the Catholic Media Association. She recently corresponded with Philip Byers to discuss the book, its reception, and her current research.

Philip Byers: Soldiers of God in a Secular World reconstructs and analyzes the rise of the nouvelle théologie, a strain of Catholic theology that first arose in the 1920s and 1930s. Introduce us to the thinkers behind this movement and to the contexts—both geographical and temporal—in which they formulated their ideas.

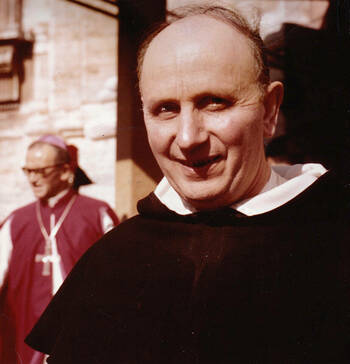

Sarah Shortall: The book centers on what is known today as the nouvelle théologie (though it’s important to point out that this term was not actually used by the actors usually associated with it). It was developed in the first half of the 20th century by a group of Jesuit theologians, including Henri de Lubac, Jean Daniélou, Yves de Montcheuil, Henri Bouillard, and Gaston Fessard, as well as Dominicans such as Marie-Dominique Chenu and Yves Congar. And it would eventually become one of the leading theological forces behind the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s.

These figures came of age at a unique moment in the history of France and of the Church. Around the turn of the 20th century, the French Republic launched an anticlerical campaign that evicted most religious orders from France and culminated in the separation of Church and state in 1905. As a result, these priests completed much of their religious formation in exile, and part of what I try to show in the book is the unexpected ways in which this experience of exile and the anticlerical campaign more generally actually created the conditions for a major renaissance in Catholic theology. It forced them to reimagine the nature of the Church and its relationship to the political order, for instance, as they grappled with the key quandary facing the Catholic Church in the 20th century: how to maintain a public role for itself once the institutions of public life had been secularized. How could the Church play a robust role in the secular public sphere without compromising its values in the process? Not all Catholics, even within the ranks of the nouvelle théologie, answered this question in the same way, and the book is about the different responses that Catholic theologians developed to this question.

In addition to the anticlerical campaign, the First World War, in which many of these priests served, was equally formative. Together, the experience of exile and of the trenches convinced the “new theologians” of the urgent need for new theological tools capable of bridging the gulf between the Church and the modern world. And in order to do this, I argue, they actually turned back to the oldest sources of the Catholic tradition—the works of the Church Fathers and of Thomas Aquinas.

PB: Central to your story is the contention that these priests viewed “the political role of the Church [as] above all a critical one,” a posture you label as “counter-politics.” Could you say a bit more about this theme and what you mean by “counter-politics”?

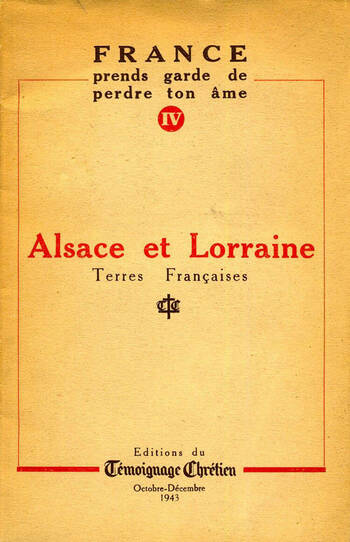

SS: Probably the best example of what I mean by “counter-politics” is the “spiritual resistance” to Nazism during the Second World War, when France fell under German occupation. At the forefront of this movement were the Jesuits associated with the nouvelle théologie, including Henri de Lubac, Gaston Fessard, Yves de Montcheuil, and Pierre Chaillet. At first, they tried to communicate their resistance message through officially sanctioned publications that were subject to censorship by the collaborationist Vichy government. In this context, I argue, they managed to outwit the Vichy censor by encoding their resistance message in the ostensibly apolitical language of theology. But by late 1941, most of these newspapers had been shut down and the Jesuits were forced underground, launching the clandestine newspaper Témoignage chrétien (“Christian Witness”), which quickly became the leading voice of the spiritual resistance.

What intrigued me about Témoignage chrétien was that the Jesuits behind it always insisted that their resistance activities more generally were purely spiritual and not political acts. This is why I characterize their work as a form of “counter-politics.” What I mean by that is that theology gave these priests a way to intervene in politics while claiming to remain at arm’s length from it and engaging in a critique of secular political ideologies. Crucially, this doesn’t mean that their work actually was above politics. Instead, I argue that the very claim to remain above or outside politics was itself politically powerful, especially in the context of the war and occupation. Not only did it allow these priests to circumvent state censorship, but framing their resistance as a spiritual act and Nazism as a religious rather than a political threat also allowed them to weigh in on political matters that might otherwise seem beyond the purview of priests. It allowed them to present Christianity—rather than, say, liberal democracy—as the best weapon against fascism. So, I argue that the political power of the spiritual resistance came precisely from its claim to be something other than a political project.

Having said that, this “counter-political” approach was not just confined to the context of the war. The Jesuits associated with the nouvelle théologie understood it more generally as a way for the Church to claim a public role in a secular political context without compromising its values in the process. As I try to show, they consistently looked to Catholic theology as an alternative to the secular political ideologies of their day, from fascism to communism to liberalism. And this is why their “counter-politics” doesn’t really fit into the categories we tend to employ to make sense of secular politics, such as “right” and “left” or “liberal” and “conservative.”

PB: A key part of your argument involves the long-term influence of the nouvelle théologie on modern Catholicism outside of France. Describe for us some of the ways this school of thought ramified around the world in the 20th century.

SS: The nouvelle théologie was condemned by the Vatican in the 1950s, but as I indicate in the last chapter of the book, this was by no means the end of the story. In the first place, these figures ended up putting their stamp on the teachings of the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. Though it initially seemed as though the council would be dominated by the opponents of the nouvelle théologie, an unexpected reversal at the first session in 1962 gave these theologians a crucial role in drafting many of the council documents. As a result, they were able to shape the council’s teachings on revelation, ecumenism, ecclesiology, and the Church’s relationship to the modern world, among other things. But the divisions that I identify within the nouvelle théologie itself—especially between the Dominicans and the Jesuits—also manifested themselves at the council and especially in the post-conciliar debates between “progressives” and “conservatives” about how to strike the right balance between adapting to the modern world and refusing those aspects of modernity that violate Catholic teaching. I also try to suggest the limits of these categories, though, by pointing out the ways in which both “progressives” like Pope Francis and “conservatives” like Pope Benedict XVI have been influenced by the nouvelle théologie.

I develop this point a bit further in the epilogue by tracing the influence of these theologians on contemporary debates within and beyond the Church about the role of religion in public life. Their ideas were taken up and transformed by Latin American liberation theologians (many of whom studied in Europe with the “new theologians”), as well as by postliberal theologians associated with the radical orthodoxy movement such as John Milbank. In addition, I highlight the various ways in which the nouvelle théologie has anticipated current debates about secularization and the public place of religion among secular scholars, such as the critique of secularism articulated by people like Talal Asad and Saba Mahmood, theories of secularization developed by Charles Taylor and Marcel Gauchet, and the recent “turn to religion” in continental philosophy. A major goal of the book is to show how closely secular philosophers in France (such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Alexandre Kojève, among others) were in dialogue with the Catholic theologians I study. I see the more recent “turn to religion” in continental thought as the natural outgrowth of these mid-century debates and as evidence that the relationship between secular thought and theology was and remains much more porous than many scholars have assumed.

PB: Your book has been lauded by readers in numerous disciplines and fields: theologians and historians, specialists who study modern Europe and others who focus on the Church. Tell us a bit about what you’ve learned after a year-plus of discussing the finished book and engaging with its reviewers—have your perspectives evolved in any specific ways?

SS: I’ve been both surprised and really encouraged by the reception of the book so far. I’m especially pleased that both theologians and secular historians or political theorists are engaging with it, since a major goal of the book was to try to bridge these sorts of disciplinary and confessional divisions. I wanted to show historians who might have no interest in Catholic thought why they should care about the history of theology, and the extent to which theology has shaped the history of European thought in the 20th century. So the interdisciplinary response has been very encouraging. Likewise, because I’m a historian and not a theologian or philosopher, I’ve been somewhat surprised by how much the reception of the book has focused on its normative implications. Though I do think the story of the nouvelle théologie has important implications for how scholars understand the role of religion in public life, my interest in these figures is largely historical and I hadn’t given much thought to the question of what value these ideas might have for our own political moment. So I’ve appreciated being pushed to think through those implications a little more deeply by scholars in disciplines that are more oriented to prescriptive or normative questions than historians tend to be.

PB: Your next book, tentatively titled Planetary Catholicism, will focus on figures including Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., whom you describe in Soldiers of God in a Secular World as “develop[ing] a distinctive theory of evolution that wove together the insights of theology and paleontology.” What drew you to this topic and these people?

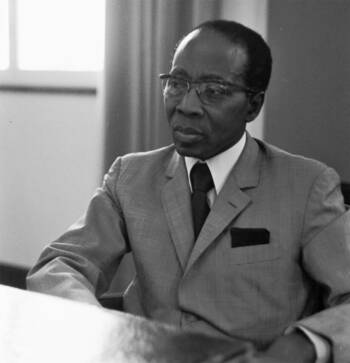

SS: As you suggest, Teilhard de Chardin appears as a minor character in my first book. He was a French Jesuit and a professional paleontologist who developed an elaborate mystico-scientific theory of evolution that was so controversial his superiors barred him from publishing on the subject during his lifetime. What initially drew me toward exploring his legacy further was my discovery of a book that Léopold Sédar Senghor—the poet of Negritude and first President of Senegal—wrote about Teilhard. From there, I began to discover more and more unlikely disciples of this idiosyncratic priest-scientist, including several Secretaries-General of the UN, modernist architects like Le Corbusier, scientists like Julian Huxley and Joseph Needham, politicians like Senghor, and writers like Flannery O’Connor. Many of these figures were not Catholics themselves but were nevertheless drawn to Teilhard’s distinctive fusion of science and religion, as well as his theory that human life on earth was converging to form a single planetary consciousness. That led me to reflect more on the various ways that Catholics have imagined the global as a theological, ecological, and political concept, and how their understanding of global order has interacted with other forms of global consciousness rooted in science, the law, politics, or the economy. It occurred to me that exploring the reception of Teilhard’s ideas (among other case studies) might serve as a useful lens through which to explore these sorts of questions and to write a broader global history of postwar Catholicism. While that history tends to be told from the vantage point of the Vatican and the central institutions of Church hierarchy, I’m interested in how the story might look different if we tell it through liminal or marginal figures like Teilhard and his disciples.

PB: We know you’re in the early stages of the project, but what are the next steps in your research?

SS: At the moment, I’m still deciding whether the book will just focus on the reception of Teilhard de Chardin or whether that will form one of several case studies in a broader exploration of Catholic visions of global order. I just finished an article on Teilhard’s influence at the United Nations, which looks at how his theory of planetary convergence was taken up by several Secretaries General and UN bureaucrats. But I’ve also written essays that explore some of the methodological questions I want to probe in the book. For instance, I recently published an essay in the Bloomsbury Cultural History of Ideas series that narrates the global history of 20th-century Catholicism through the Eucharist. My goal there was to develop a framework for how one might write a global history of religious thought that is geographically expansive but does not sacrifice contextual specificity, by using the fairly narrow lens of Eucharistic theology to tell the much larger global history of Catholicism in the 20th century, as it grappled with the challenges of secularization, totalitarianism, global inequality, and decolonization. More recently, I just finished an essay on the theological contribution to Third Worldism and the effort to decolonize Christian theology that looks at the history of the Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians. So, at the moment I’m using these projects to flesh out the research for my new book and to determine the exact scope of the project.

Philip Byers is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center.