Daniel Gullotta is a Ph.D. candidate at Stanford University specializing in American religious history and has been appointed as the Archer Fellow in Residence at the Ashbrook Center at Ashland University. He received his M.A.R. from Yale Divinity School and his M.T.S. from the Australian Catholic University. He won a Research Travel Grant from the Cushwa Center in 2021 for his project “Voting Papists: Catholics and Anti-Catholicism in the Making of Jacksonian Democracy,” and Philip Byers recently corresponded with him to learn more about the research.

Philip Byers: Your project studies the religious subjects who factored in the rise of Andrew Jackson. These weren’t the Methodists and Baptists that scholars often feature in treatments of the era’s religious life—tell us about your interest in the diverse religious traditions that formed the basis of Jackson’s support.

Daniel Gullotta: If one were to pick up any number of the books concerning religious politics in the 19th century you most likely find a very one-sided story, a story that focuses almost exclusively on American evangelicals and, by extension, the Whig Party. Having said this, it has been common knowledge for a long time among historians that Catholics, Jews, Mormons, Lutherans, Episcopalians, and Freethinkers (just to name a few) were most often found within the wings of the Democratic Party of the 19th century. Yet, no one has really stopped to ask why: How did the two political parties end up like this? Once I realized that the Jacksonians also cared about religion and that religious issues also mattered to Democratic voters in the early 19th century, I knew I had a great subject on my hands.

PB: Your grant proposal described your quest to get “deeper into understanding religious coalition building.” Popular perceptions of this period are sometimes framed by the notion of “ethnic enclaves,” the idea that Catholics—often recent immigrants—were insulated from the broader culture, but you contend otherwise. What role did U.S. Catholics play in Jacksonian coalition-building?

DG: Much of this occurred even before Jackson considered running for president. Catholics, just like most of their Protestant and Jewish co-citizens, were enraptured by Jackson’s victory at New Orleans and contributed to his celebrity. But Catholics saw in Jackson some unique qualities as well; after all, New Orleans was understood as a deeply Catholic city, so Jackson as its defender garnered a special place in the heart of many American Catholics, as did his attendance of a celebratory Mass following the battle. Additionally, early and later Irish Catholic immigrants saw a kindred spirit in Jackson given his Scotch-Irish ancestry. Also, Jackson was close friends with many of the United States’ most famous Catholics, such as Roger B. Taney, a point that did not go unnoticed by many anti-Jackson papers during the elections of 1824 and 1828. Simply put, Catholics were not too different from their neighbors with regards to being enamored with Jackson’s status as a war hero, but they also saw in him other qualities that made him their ideal candidate.

PB: Who were some of the key Catholic actors that figure in your story?

DG: Roger B. Taney is easily the most important Catholic in my story and plays a defining role in solidifying the place of Catholics in the emerging Democratic Party. While Taney is rightly remembered today for his role in the Dred Scott decision, the fact that he was the first Catholic seated on the Supreme Court seems to be entirely forgotten. Given how many Catholics sit on the Supreme Court today, this fact might strike us as banal, but at the time it was highly controversial and sparked outrage within evangelical circles (some of whom had voted for Jackson). By appointing a “papist” to the highest court in the land, Jackson shocked evangelicals, many of whom felt blind-sided or even betrayed. Some would abandon him for the anti-Jacksonian coalition that was forming into the Whig Party.

PB: We always love to learn more about a researcher’s experience in the Notre Dame Archives. Did you encounter any sources that especially intrigued you?

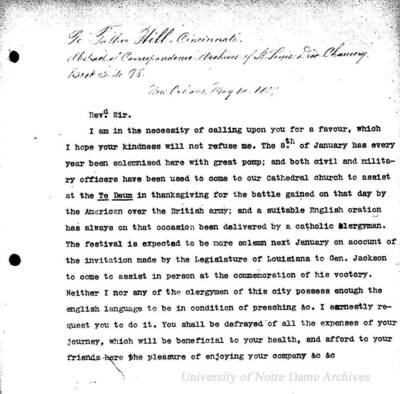

DG: Probably the most fascinating document I found was a letter from the Charles Leon Souvay Collection, discussing an 1828 sermon delivered by a Father Hill of Cincinnati, commemorating the Battle of New Orleans. At the time, remembering the Battle of New Orleans was an annual event almost on the same level as celebrating the 4th of July, and because 1828 marked the rematch between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson for the presidency, tensions were running high to say the least! Beyond that, offhanded comments from the diaries and letters of various Catholic missionaries and priests were also interesting, mentioning that they were reading things like The Life of Andrew Jackson by John Eaton, demonstrating just how consumed they were, like most of the nation, in Jacksonmania.

PB: You are very visible online—you’ve established a strong presence on social media, and you created and host the popular podcast The Age of Jackson. How have these various opportunities come about, and how do you conceive your role as a scholar with both academic and public audiences?

DG: The podcast was created purely out of what I felt to be a need in the educational podcasting space, as the early 19th century was so absent. Its success, I must admit, has taken me by surprise but I am pleased with it. With my move to the Ashbrook Center at Ashland University, the podcast is transforming and expanding. It is now going to be The Age of Lincoln, so we can incorporate even more scholars and their work. Doing the podcast, as well as writing for the public in outlets like The Bulwark, is a great love of mine because they are different components of my work, but equally as important as archival research, scholarly writing, and presenting at conferences. Given recent events, this public outreach might be even more important. But I have always believed public outreach is a scholar’s duty and a calling I do not take lightly.

PB: With all those public projects and a dissertation to finish, you have no shortage of work to keep you busy. What do you imagine is the next step for this project?

DG: My agent and I plan to shop the manuscript to various university presses when the time is right. I am already thinking about future projects that relate to this one, such as a religious biography of John Quincy Adams, but one step at a time.