Stephen Bullivant’s Nonverts is one of the latest in a series of recent books and reports documenting the decline of religious affiliation in North America, especially among young adults.1 As he notes, “Across all US cradle Catholics born since 1970, a ‘Catholic upbringing’ has produced twice as many nones [21%] as it has weekly Mass-going Catholics [10%].”2 In addition to explicit nones, even more young adults are Catholic in name only, rarely attending religious observances and knowing or believing little of the tenets of their putative faith. Nationally, the number of baptisms in the United States has declined by 57% between 1970 and 2020, and the number of Catholic marriages by 78%.3

While the exodus of young Americans from Catholicism has been offset by an influx of Catholic immigrants from Latin America, Africa, and Asia, this may be only a temporary reprieve. Evidence shows that the children and grandchildren of today’s immigrants are quickly assimilating to secular American culture, just as previous generations of Italian, Polish, or Irish immigrants did.4 And the countries these immigrants have come from are less Catholic than they once were. A recent survey by the Latin American and Caribbean Episcopal Council has found that the number of annual baptisms, confirmations, and Catholic marriages in their dioceses has fallen. The bishops noted that this seemed to indicate that there was a widespread weakening of Catholic affiliation there.5 Secular studies confirm this: a survey by Latinobarómetro found that the percentage of Argentines identifying as Catholic fell from 76% in 2010 to 49% in 2020.6

This decline, researchers say, is due to several factors. For one thing, it is now more acceptable—even normal—to be a religious “none” today.7 In fact, in many social milieux, expressing any overt religiosity would be considered deviant. Religious persons are seen as dogmatically rigid, hypocritical, repressive, and intolerant—all values that are diametrically opposed to the values young adults have been socialized to hold dear. Sex scandals in both Catholicism and several Protestant denominations have led to a widespread distrust of institutional religion: one study8 found that less than a quarter of those who have left Christian churches have any confidence at all in religious institutions, with former Catholics expressing the least confidence (21%). Additionally, the stereotype of religion in the United States has become conflated with media depictions of Protestant evangelicalism: heavily supportive of Donald Trump, repressive of women, and rejecting scientific findings on evolution and climate change. That many religious denominations and individuals do not correspond to this stereotype is irrelevant. To quote an early sociologist,9 if people believe something is true they will behave as if it is and, in this case, they will prefer to be identified as a “none” rather than to be suspected of being religious.

Religious orders: Signs in service

What does this mean for the future of the Catholic Church in North America? And what does it mean for the future of religious orders?10 I have argued elsewhere11 that religious orders have performed several essential services for Catholicism throughout its history. For one thing, every religious tradition contains adherents who differ in their ability and desire to follow its teachings. Some are content with the bare minimum of observance; others desire much more. Some excel in the highest of their faith’s spiritual practices (ecstatic prayer, prophecy, mendicant preaching), others do not. If “religious virtuosi” do not have an outlet for their fervor in their own faith tradition, they will go elsewhere. The lack of religious orders in most Protestant denominations is precisely the reason that the virtuosi within their ranks have periodically split off into stricter sectarian groups: Methodists splitting from Anglicans, Wesleyan Holiness churches from Methodists, and so on. By keeping its religious virtuosi in religious orders, Catholicism has usually, but not always, avoided this fate.

A second essential role that religious orders have historically played is to serve as spiritual laboratories, adapting the Church’s rituals and practices in response to emerging needs in the larger society.12 Thus, the 12th-century mendicant orders helped the Church adapt to the revival of cities and a new merchant class. They comprised most of the faculty of the new medieval universities, and developed a theology legitimating money-making, profit, and interest—practices that had been considered sinful in previous centuries. They also added new elements to popular devotion: Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote poems and hymns (Pange Lingua, Adoro Te Devote, Lauda Sion) that are still sung today; Saint Francis, it is said, erected the first nativity scene. Medieval nuns were instrumental in increasing popular acceptance of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. In the 16th century, Saint Ignatius and the Jesuits developed the idea of the religious retreat using the Spiritual Exercises. Seventeenth-century women religious in England and France pioneered the ministry of educating young girls, which had previously been considered an unsuitable work for their sex. In the 18th and 19th centuries, religious orders created or popularized devotional practices such as Forty Hours, parish missions, and novenas to the Sacred Heart or particular saints, and also established hospitals and schools for immigrants and the urban poor.

A third service that religious orders have performed for the Church is evangelization, both of non-Christian peoples in far-distant lands and also among uncatechized populations in their own countries. Early Irish monasteries sent missionaries to catechize Northern Europe; Jesuits and Franciscans sent their members to convert the inhabitants of the newly discovered Americas. As recently as 1992, almost 90% of U.S. Catholic missionaries ministering overseas were members of male and female religious orders.

. . . religious orders are necessary to Catholicism, not merely to staff schools and hospitals as they did 50 or 60 years ago but, more importantly, to lead the Church in responding to the unique and particular spiritual hungers of each generation . . .

I would argue that religious orders are necessary to Catholicism, not merely to staff schools and hospitals as they did 50 or 60 years ago but, more importantly, to lead the Church in responding to the unique and particular spiritual hungers of each generation in our societies today. Otherwise, we will lose young adults to other spiritual beliefs and practices. For example, the places in the United States and Canada where formal religious adherence is weakest (primarily in Washington, Oregon, and northern California in the United States, and in British Columbia in Canada) are precisely the locations where quasi-religious beliefs and practices—from astrology and crystals to new religions like Heaven’s Gate and the Peoples Temple—draw the most adherents.13 In the pluralist religious market of the United States, the Church needs its religious orders to model how the timeless call of Jesus can speak to young adults today.

But throughout the Northern Hemisphere, and in many parts of the Southern Hemisphere as well, religious orders are shrinking and the few remaining members are aging. From a peak of over 180,000 in 1965, the number of sisters in the United States has dwindled to less than 45,000 and their median age is in the mid to late 70s.14 Religious orders in Canada, Ireland, and Western Europe have experienced similar, or even larger, declines. In Mexico, the number of young women entering religious orders is decreasing, and the median age of sisters there is 62.15 Religious orders of men are also declining.16 On the other hand, several Asian countries have seen an increase in the number of entrants to religious orders, although there is evidence that this may be slowing down more recently.17 In Africa, the number of women’s religious orders has almost tripled, as has the total number of sisters in them. In Latin America, the number of women religious in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala has more than doubled.18 Many religious priests and sisters from these countries now engage in “reverse mission,” coming to parishes in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe to fill the ministries once held by the native-born clergy and sisters here. But few young adults in North America and Europe join these newly-arrived orders after they come, in sharp contrast to the large numbers of Americans and Canadians who joined the religious orders sent from Europe in the 19th century.19

Today’s religious: Desires, hopes, and challenges

If the Catholic Church is to remain a large and influential presence in an increasingly secular North America and Europe, it must offer the younger generations here the lifestyles and worldviews that speak to their deepest spiritual hungers, hungers that are still present in the hearts of even the most secularized nones. A thriving population of women’s and men’s religious orders is, I believe, essential for this to happen.

Over the past ten years, researchers at the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) at Georgetown University have produced several books on religious orders and the young adults who enter them, both in the United States and in other countries around the world. The earliest of these, New Generations of Catholic Sisters,20 compared women who entered religious life in the United States between 1965 and 1980 with women who entered between 1993 and 2008. Pathways to Religious Life21 looked at the familial, educational, parish and volunteer experiences that lead young men and women to enter religious orders. This book also described some of the emerging trends in religious vocations in the United States: the lay associate programs in established orders as well as the many newly forming religious communities springing up (and often quickly dissolving) here. Migration for Mission22 looked specifically at international sisters coming to live and minister in the United States, whether by joining a U.S.-based order or by being sent as their order’s “reverse missionaries” to revitalize a secularized American Church. New Faces, New Possibilities23 also focused primarily on women’s religious orders in the United States, but looked at the implications of their growing ethnic and cultural diversity—especially the evolution of the orders’ leadership/governance and the challenges of living in a multi-ethnic community. Most recently, God’s Call is Everywhere24 broadened its focus beyond the United States, comparing studies of women entering religious life since 2000 in this country with those entering in Australia, Canada, France, Ireland, and the United Kingdom. The book also contains additional chapters covering women religious in Mexico, India, and Kenya.

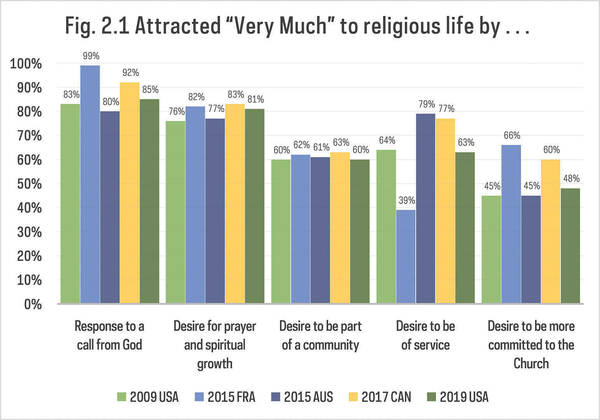

What have these studies found? There were several common themes in the answers of the women entering religious life across all countries and at all ages. Universally, the sisters cited a call from God as their main reason for entering. Also important was a desire for spiritual growth and community living, even though the researchers noted that “while community life is one of the primary ideals, it can also present one of the primary challenges.”25 Common living, common prayer, and common ministry were especially important for the youngest sisters,26 but they were also aware of the challenges posed by living and ministering in culturally and generationally diverse communities.27

The universal themes of a call from God, a desire for spiritual growth, and the attraction of community life were, however, filtered through the specific cultural, economic, and demographic circumstances that the women encountered, both in their chosen order and in the larger society.28 In North America, Australia, Western Europe, and (to a certain extent) Mexico, there are few new entrants to religious institutes, and the median age of the members in most institutes is in the upper 70s or higher. This causes an age gap in the orders that have only one or two young members. In other orders, the complete absence of any new members at all can affect the way their members view the future of their own order and of religious life as a whole. This has implications for the amount of effort the sisters may be willing to devote to inviting women to join them and/or forming them once there.

Another factor influencing whether a young woman will respond to God’s call is the ethnic composition or class structure of her larger society. Divisions in the larger society may be replicated in religious life. If so, whole categories of women may be deterred from entering an order where most of the members are of a different race, ethnic group, or social class than their own. If a woman does enter such an institute, ethnic and class distinctions may make it difficult for her to remain in her vocation, especially if these distinctions operate at an unconscious or unacknowledged level in the receiving community.

Class and ethnicity may also be correlated to the amount of education available to women in a society. In countries where higher education is available to women, a postsecondary education may come to be expected of all entrants, thus screening out those whose class status has precluded this. At the same time, the women who do have more education will have more professional opportunities available to them in the larger society, and may be less interested in entering a religious order. Those who do enter may chafe at formation programs that do not take into account their prior educational or professional experience. On the other hand, in countries where education is less available, women may be motivated to enter a religious order in order to obtain an education rather than from a divine call.

In addition to shaping whether and how a woman will respond to God’s call, the specific situations in her society will also influence the kinds of obstacles which may discourage her. Across all of the countries studied in God’s Call is Everywhere except for Kenya, the women surveyed or interviewed cited the negative impact of secularism on religious vocations, saying that it increases materialism and individualism among the young. Poor theological catechesis and inadequate formation in prayer were other obstacles the sisters mentioned, as was the incessant bombardment of electronic stimuli. The sisters felt that the ability to be silent in prayer was essential to religious life, but they said this was extremely difficult to do. Another frequently cited obstacle was negative media depictions of sisters: that sisters are obsolete, aging, and dying out (United States), that they are cloistered and walled away from the real world (France and Mexico), or that they are morally compromised by scandals in their ministries (Ireland). At the same time, new entrants cite positive (even if highly fictionalized) media depictions of sisters as a factor that drew them to enter—but one that causes a different set of problems when they encounter less-than-perfect sisters in daily living.

Weighing options

Prior to the mid-20th century in North America and Western Europe, and still today in some African, Asian, and Latin American societies, young Catholics grew up in a culture where their religion was omnipresent. They went to schools run by religious priests and sisters, and the young women and men who entered religious life or the priesthood were esteemed by their families and culture. But such all-encompassing Catholic socialization is rare today in Western countries, and in some societies may not occur at all. Far from being culturally valued, entering a religious order may be stigmatized, especially in countries where the dynamics of a previously dominant Catholic culture have been called into serious question by the scandal of abuse. As the researchers of the United Kingdom and Ireland study noted, “In Ireland, which was formerly considered a ‘Catholic country’ where the prevailing culture was deeply embedded in the majority Catholic faith, it is no longer possible to assume that young people have any effective connection with the Church or with religious at all.”29 The CARA studies all show that men and women with a Catholic background, both in the family and at school, are more likely to consider a religious vocation than those who grew up in more secular or even antireligious environments. Such environments offer few opportunities to meet sisters and get to know them or even to see them at all. This difficulty was cited by sisters in the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and France.

I stated at the beginning of this essay that I believe various forms of religious life have been necessary to Catholicism in the past: providing a valued outlet for those who desire to do or be more for their faith and also leading the Church’s response to the spiritual hungers and cultural discontinuities particular to each generation and each society. What worries me is that the development of ideological divisions within the Church, replicating the “Big Sort”30 we see in the larger American society, may prevent religious orders from fulfilling the valuable role they once had in Catholicism. Religion can come to be identified with one pole of the culture war, so that organizations, media outlets, or political groups are increasingly ignorant of, or even hostile to, religious worldviews and perspectives. Valuable collaboration between religious and other nonprofit organizations may never happen; positive stories about religion may never be told, government policies may be formulated without input from religion (or input from only one ideological pole of religion).

I fear that Catholicism itself is becoming polarized, with one side seeing itself as the only true exemplar of faith and practice and denigrating any different way of “being Catholic.” A recent study of priests and bishops, conducted by The Catholic Project at The Catholic University of America, found that none of the priests ordained after 2020 identified themselves as theologically liberal or progressive.31 In many dioceses, Catholic social teaching has been dropped from the recommended curriculum for Catholic schools and religious education programs. The Australian study in God’s Call is Everywhere noted that such ideological and theological polarization seemed to occur more among religious orders in the United States than in their own country.32 Such polarization will “turn off” those who desire a different way to live Catholicism. Whole groups of young adults may then never consider being religious, let alone entering a religious order. And the Church in this country—and other countries—will suffer as a result.

What can be done to avoid the diminishment and collapse of Catholicism in the face of the inexorable tide of secular culture? Are religious orders also doomed to extinction as their recruitment sources dry up? Or can the orders once more fulfill their historical role of leading Catholicism to respond compellingly to the hungers and discontinuities of today’s cultures?

At the end of his book, Bullivant cites Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option as one answer to these questions. As Bullivant and Dreher see it, this “involves a conscious seeking out of like-minded Christians, and the forming of mutually supportive networks in which being and practicing a serious version of Christianity is the norm.”33 The difficulty, however, is saying exactly what “a serious version of Christianity” is. And is there only one version that should be prescribed for everyone? A “Benedict Option” conceived in this manner will be unappealing to the majority of young adults in our society. Catholicism or Christianity will then remain, as Bullivant puts it, “a medium town on a fair-sized knoll”34 or, worse still, an encapsulated village in the societal boondocks—ignored, ridiculed, or forgotten.

There could be many versions of the Benedict Option: our faith is wide and deep enough for all of them.

This is where, I believe, Catholic religious orders could play an essential role. Catholicism is too wide and deep a religious tradition ever to be reduced to a single “serious version.” There is indeed a place for “a medium town on a fair-sized knoll” that practices the Catholicism remembered and romanticized from the Catholic neighborhoods of the 1950s. Several religious orders are already helping this version to thrive in its niche. But there are other hungers and discontinuities in our North American and Western European societies today: the need for contemplation and prayer in the midst of omnipresent and intrusive electronic media, caring for the earth as Pope Francis called for in Laudato Si' and Laudate Deum, the plight of the waves of immigrants and asylum seekers, the burgeoning numbers of homeless persons in our country (which have increased 12% just in the past year), and the “tribalization” of red and blue Americans who increasingly see each other as enemies beyond redemption. There could be many versions of the Benedict Option: our faith is wide and deep enough for all of them. Why not have a religious field of ten, or one hundred, or one thousand medium-sized towns on fair-sized knolls, each linked to the others in friendly and mutual admiration, learning from each other and encouraging each other to grow? New and existing religious orders could—and should—be the pioneers to establish them, and the focal points around which they can all grow and thrive. If Catholic religious life succeeds in doing so, we will see a “New Awakening” in our country. It has happened many times before in the past 2,000 years. Religious orders—with a wide variety of charisms and ministries—can help it happen again.

Patricia Wittberg, S.C., Ph.D., is a research associate at the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) in Washington, D.C., and professor emeritus at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis.

Feature image: The welcome ceremony for World Youth Day in Lisbon, Portugal, on August 3, 2023. Photo by Mick Haupt via Unsplash.

This article appears in the spring 2024 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.

Notes

1 An extensive (but not exhaustive) list of these can be found in Patricia Wittberg, S.C., “The Role of Small Christian Communities for Catholic Young Adults: Differences by Gender and Ethnicity.” In Thomas P. Gaunt, S.J., ed. Faith and Spiritual Life of Young Adult Catholics in a Rising Hispanic Church, Liturgical Press, 2022, pp. 39–41.

2 Bullivant, Stephen, Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America. Oxford University Press, 2022, pp. 187–188, 244n17.

3 “Socioeconomic Factors Relating to Parish Growth and Decline.” The CARA Report, vol. 29, no. 3, Winter 2024, p. 9.

4 Patricia Wittberg, S.C., Catholic Cultures: How Parishes Can Respond to the Changing Face of Catholicism. Liturgical Press, 2016, pp. 43–45. See also Patricia Wittberg, S.C., “The Role of Small Christian Communities for Catholic Young Adults: Differences by Gender and Ethnicity.” Op. cit., p. 43.

5 Luke Coppen, “Study: Sacraments in decline in Latin America.” The Pillar, October 21, 2023.

6 As reported in the Washington Post, Dec. 15, 2023.

7 An argument made by Joel Thiessen and Sarah Wilkins-LaFlamme in None of the Above: Non-Religious Identity in the US and Canada. New York University Press, 2020, pp. 9–10.

8 Jim Davis, Michael Graham, and Ryan Burge, The Great Dechurching. Zondervan, 2023, p. 73.

9 W. I. Thomas first articulated the theorem named after him: “If men [sic] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” See wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_theorem.

10 I realize that “religious order” is only one of several canonical types of vowed religious: there are also pontifical and diocesan religious congregations, apostolic societies, secular institutes, public and private associations of the faithful, papal prelatures, etc. For the sake of simplicity, I am using the term “religious order” to refer to all these groups.

11 Roger Finke and Patricia Wittberg, S.C., “Organizational Revival from Within: Explaining Revivalism and Reform in the Roman Catholic Church.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, vol. 39, no. 2 (2000), pp. 154–170.

12 See Patricia Wittberg, S.C., Mary L. Gautier, Gemma Simmonds, C.J., and Nathalie Becquart, X.M.C.J., God’s Call is Everywhere: A Global Analysis of Contemporary Religious Vocations for Women. Liturgical Press 2023, pp. 3–4 for the examples in this and the following paragraph.

13 Tara Isabella Burton, “Rational Magic,” The New Atlantis, Number 72, Spring 2023, pp. 3–17.

14 Mary L. Gautier, “Population Trends Among Religious Institutes Since 1970.” In Thomas P. Gaunt, S.J., ed. Pathways to Religious Life, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 16–17.

15 Luis Fernando Falco, “Women’s Religious Life Vocations in Mexico: Elements for Further Reflection.” In God’s Call is Everywhere, op. cit. p. 143–144.

16 Mary L. Gautier, “Population Trends Among Religious Institutes Since 1970.” Op. cit., pp. 25–32.

17 See Sister Patricia Murray, I.B.V.M., foreword to God’s Call is Everywhere, op. cit., p. xiii.

18 Patricia Wittberg, S.C., and Thu T. Do, L.H.C., “International Religious Institutes in the United States.” In Thomas P. Gaunt, S.J., and Thu T. Do, L.H.C., New Faces, New Possibilities: Cultural Diversity and Structural Change in Institutes of Women Religious. Liturgical Press, 2022, pp. 54–55.

19 “International Religious Institutes in the United States,” op. cit., pp. 69–71.

20 Mary Johnson, S.N.D. de N., Patricia Wittberg, S.C., and Mary L. Gautier, New Generations of Catholic Sisters; The Challenge of Diversity. Oxford University Press, 2014.

21 Thomas P. Gaunt, S.J., ed. Pathways to Religious Life. Oxford University Press, 2018.

22 Mary Johnson, S.N.D. de N., Mary L. Gautier, Patricia Wittberg, S.C., and Thu T. Do, L.H.C., Migration for Mission: International Catholic Sisters in the United States. Oxford University Press, 2019.

23 Thomas P. Gaunt, S.J., and Thu T. Do, L.H.C., New Faces, New Possibilities: Cultural Diversity and Structural Change in Institutes of Women Religious. Liturgical Press, 2022.

24 Patricia Wittberg, S.C., Mary L. Gautier, Gemma Simmonds, C.J., and Nathalie Becquart, X.M.C.J., God’s Call is Everywhere: A Global Analysis of Contemporary Religious Vocations for Women. Liturgical Press, 2023.

25 Quoted in God’s Call is Everywhere, p. 67.

26 New Generations, pp. 114–117.

27 New Faces, New Possibilities, pp. 76–78.

28 The information in this and the next 3 paragraphs is a summary of God’s Call is Everywhere, pp. 203–206.

29 Quoted in God’s Call is Everywhere, p. 82.

30 Bill Bishop, The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America is Tearing Us Apart. Houghton Mifflin, 2008.

31 Luke Coppen, “Study: Liberal US priests facing ‘progressive’ extinction.” The Pillar, November 7, 2023. Also summarized in The CARA Report, vol. 29, no. 3, p. 11.