Gráinne McEvoy

Gráinne McEvoy

Gráinne McEvoy is an Irish Research Council Government of Ireland postdoctoral fellow at Trinity College Dublin. She holds a Ph.D. in history from Boston College and received a Theodore M. Hesburgh Research Travel Grant from the Cushwa Center in spring 2017 to support work on her book project, "God at the Gates: American Catholic Social Thought and Immigration Policy, 1910–1965." It examines how American Catholic social critics engaged in the reform of immigration policy from the introduction of literacy testing to the removal of the national origins quota system. Her research incorporates religious ideas, especially on the family, more fully into American immigration history. Cushwa postdoctoral fellow Catherine Osborne checked in with McEvoy early in June about her project.

CO: Most American historians have two major immigration-law dates firmly in mind: 1924 and 1965. What made you decide to start your project in 1910 rather than in the mid-1920s?

GM: Yes—1924 and 1965 are typically the two milestones of U.S. immigration history in the 20th century. The immigration laws enacted in these years more or less bookend the period when admission to the country was restricted according to the national origins quota system, and this time period is the main frame of my project. To understand the rationale behind immigration restriction in this period, however, we need to take a long run at the restrictive legislation of the 1920s. Historians of immigration policy history have been doing this for quite some time, looking at the Chinese exclusions of the 1870s and ’80s, for example, or state-level restrictions much earlier in the 19th century that anticipated federal immigration laws. I’ve decided to begin my story part way through the long campaign to introduce a literacy test for all prospective immigrants. This is mainly because this was really the first concrete proposal (ultimately enacted into law in 1917) in the run up to the 1920s that Catholic leaders and social critics took a vocal, and not harmonious, stance on.

The debate over the literacy test started much earlier than 1910 (Senator Henry Cabot Lodge first introduced the proposal in an 1895 immigration bill), but it’s really only from around 1910 that I was able to identify a small group of Catholic social critics starting to vocally support immigration restriction by literacy testing. This group included Arthur Preuss and Frederick Kenkle of the German Catholic Central Verein in St. Louis and, more prominently,Monsignor John A. Ryan, leading American Catholic Social thinker of the early 20th century. Their approach to the literacy test proposal was similar to organized labor’s position: they thought that the test would stem the flow of unskilled immigrant labor, which, they believed, was degrading the wages of the American laborer. The difference was that these Catholic thinkers rooted their support for the test in Pope Leo XIII’s defense of labor in Rerum Novarum (1891), and in Monsignor Ryan’s writings on the living and family wage that stemmed from that papal encyclical. Ryan and others were worried about the effect of unchecked immigration on the material and moral wellbeing of those who were already in the country (citizens and immigrants alike) as well as those planning on immigrating. I immediately found this use of Catholic social thought and moral theology to justify immigration restriction fascinating and surprising, given how prominent American Catholic voices are in the defense of immigrant rights today. This was really the genesis of a project that has been seeking to tease out a Catholic social critique of immigration, or a theology of migration, that has resided somewhere in the middle of what is really a false binary between liberalism and conservativism on immigration law. I found that throughout the period I studied, there was a tension in this Catholic critique between the individual’s right to migrate in pursuit of family security and a living wage and the state’s right (and obligation) to control that movement for the collective good. This tension really animated the Catholic response to various immigration issues. So that’s the long answer for why I start with discussion of literacy testing in the 1910s.

CO: I’m fascinated by the movement you document from an immigration policy promoting the migration of certain races/nationalities to an immigration policy promoting certain behaviors—prioritizing families and family reunification. To what extent does Catholic theory about families overlap with Protestant social reformers who also promoted family formation, and to what extent are Catholic and Protestant pro-family discourses operating on separate tracks?

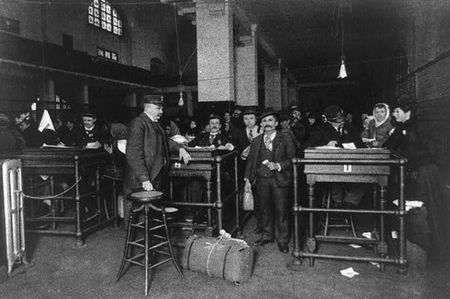

Final discharge station for immigrants at Ellis Island, 1902

Final discharge station for immigrants at Ellis Island, 1902

GM: This is something that I will look a little further into for the book manuscript, and which I had to draw a line at when writing the dissertation, in order to finish within a reasonable period! Certainly, the Catholic advocacy of family reunification in immigration law had Protestant as well as Jewish counterparts. I’ve been able to trace this most clearly in the period after World War II. The global refugee and displaced person crisis that followed the war really helped to consolidate a coalition of religious and ethnic groups, at first to push for the liberalization of extant refugee and displaced person policies, and then as the 1950s progressed to repeal the national origins quota system. This coalition was far from harmonious, especially as regards refugee admissions, and Catholics, especially those representing the national hierarchy through the National Catholic Welfare Conference, were among its more reluctant members, largely owing to a fear of being automatically committed to group decisions that they may not have fully supported. Still, I’ve been able to access ample evidence of this interfaith collaboration, which has helped demonstrate how in step Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish immigration experts became on the broad strokes of immigration reform. On the whole, by the time we get to at least the late 1950s, Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish immigration experts were in agreement that the existing nationality and race-based system had to go, and that the principle of family unity and reunification ought to form a central pillar of whatever replaced it. As for trying to trace Protestant social reformers’ position on immigration policy before 1945, however, I have had to make this line of inquiry less of a priority, mainly for pragmatic reasons. In light of what I was already doing for manuscript revisions, it would have been a bit to ambitious to plan on mining the historical record for the origins of a Protestant or Jewish theology of migration. I will, however, be able to access this earlier Protestant position to a certain degree, for example, when they spoke before the same Congressional committees as their Catholic counterparts, and I’m interested to see what their priorities were in the 1920s and ’30s.

CO: You ended your dissertation in 1965, but your book will have an extended epilogue with new research that takes the story up through the present—including consideration of Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C., and the Catholic role in immigration policy post-1965. How will the end of the book leave a reader feeling differently than the dissertation did?

Father Hesburgh with President Carter

Father Hesburgh with President Carter

GM: I think Father Hesburgh’s position in the 1980s and the Church’s more recent stance on immigration law helps to show how the tension at the heart of the Catholic critique of immigration has really persisted into the 21st century. I wanted to write additional material about the Catholic role in immigration policy post-1965 because I felt it would be the elephant in the room if I didn’t. I also felt that this would betray one of my original motivations with this project. Catholic voices have been so prominent in the debate over refugees, the undocumented, and reform of immigration law in recent decades, and, most people probably identify the Church as (for want of a better descriptor) pro-immigration. My initial findings on support for a literacy test from John Ryan and others demonstrated that the Catholic philosophy on immigration policy in the 1910s was much more complicated than simply “pro-immigrant/immigration,” and my subsequent research has shown that this continued to be the case through the 1960s. I therefore felt that reflecting on the Church’s position in more recent years, in the context of that longer history, would be extremely important, and I feel very strongly that breaking down the false binary of pro- or anti-immigration forces has to be part of the process of securing agreement on and justice in immigration reform. I think certain Catholic leaders today are very aware of this potential. Yet, I also realize that my project is and must remain a history, and I need to be very careful about reading the past too much through the present. I think this is especially important given how emotional and polarized the current debate is, not to mention how emotionally I tend respond to this debate as a migrant myself! This is why I plan to treat this post-1965 period with a light touch, and in an epilogue (rather than additional chapters) that will be reflective but informed. I’m scouting about for good models of this type of epilogue, so any suggestions would be welcome! As for how I want the reader to feel by the end of the book: I hope that the book can do something that the dissertation may only have hinted at: encourage the reader to more carefully approach the emotions and extremes around the immigration issues in our current moment, such as refugee admissions, border security, and detentions and deportations.

CO: What do you think Father Hesburgh would make of contemporary immigration debates? Having talked to several people who have worked in his immigration papers this year, I have the sense that he’s not easy to categorize politically, perhaps even in his own day, let alone in the terms of an argument thirty years later. Some of his positions seem quite “liberal” and some quite “conservative.” Leaving those categories aside, what kind of policy do you think he would promote today, regardless of whether or not it would be politically viable?

GM: This is such a great question, and something I’ve been thinking about a lot. From what I’ve looked at so far, I agree that Father Hesburgh’s position on immigration is not easy to categorize, but I think that’s only because of how, as you imply and as I’ve talked about, we too easily conceive of the immigration debate as a binary between liberal and conservative positions. If we approach the history of immigration policy reform this way, then we will indeed be confused by Father Hesburgh’s simultaneous advocacy of immigration as a benefit for society, sympathy for the plight of the undocumented, and, in his role as chairman of the Select Committee on Immigration and Refugee Policy (1979–81), his argument that securing the border was imperative to effective immigration reform. I still want to do a bit more reading around Father Hesburgh’s published speeches and articles on immigration, but my research at Notre Dame has suggested that Father Hesburgh fits into what I see as a long American Catholic tradition of pragmatic openness when it comes to immigration, respecting both the individual’s right to migrate and the state’s right and obligation to control that migration in the public interest. In this sense, consciously or not, he is part of a lineage that I would say begins with John A. Ryan’s support for the literacy test.

As for what kind of policy Father Hesburgh would promote today, that’s a tough one. I think our current climate, shaped by, for example, post-9/11 national security or the coming-of-age of the DREAMer generation, means that the dynamics of the immigration debate today are very different from that in the 1980s when Hesburgh was most vocal on this issue. But if we have to hypothesize about a Hesburgh position in 2017, I think we could most safely do so based on his desire to clarify that the most sacred family unit in immigration law should be the nuclear family (parents and minor children). Perhaps noting the quite capacious definition of family in the 1965 Immigration Act, which was designed in part to help reunite citizens and permanent residents with adult children, brothers, sisters, and parents, as well as spouses and minor children, Hesburgh and other members of the Select Committee sought to give higher preferences in immigration law to the more narrowly-defined nuclear family. For this reason, I think we can probably safely say that Father Hesburgh would be appalled by the way in which immigration enforcement has dropped the Obama-era policy of focusing primarily on deporting undocumented individuals with serious criminal records. I am sure that if he was weighing in on the discussion today, Father Hesburgh would join the chorus of Catholic leaders who are criticizing the deportation of the undocumented but otherwise law-abiding parents of American citizen children as destructive of family life and not at all conducive to reasonable reform of the nation’s immigration laws.