Jacqueline Willy Romero has joined the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center as a postdoctoral research associate for the 2021–22 academic year. Romero earned her Ph.D. in history at Arizona State University in 2019. With research interests in antebellum Catholicism, the history of women religious, trans-Atlantic migration, and the influence of gender in social institutions, Romero has presented at conferences of the American Catholic Historical Association, the Conference on the History of Women Religious, the American Historical Association, and the American Society of Church History. Her dissertation, “‘By the Labors of our Hands’: An Analysis of Labor, Gender, and the Sisters of Charity in Kentucky and Ohio, 1812–1852,” focused on two communities of women religious and offers a regional study of gender, labor, and the institutional growth of the Catholic Church in the antebellum era. Her scholarship has appeared in American Catholic Studies, where she has served as an external referee. She has also refereed for the U.S. Catholic Historian. She served during the 2020–21 academic year as a full-time teaching faculty member in Kennesaw State University’s Department of History and Philosophy. Prior to her appointment at Kennesaw State, Romero spent the 2019–20 academic year as an instructor in history for the ASU School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies.

Shane Ulbrich: You last visited Notre Dame for the Cushwa Center’s Conference on the History of Women Religious in June 2019, shortly after completing your doctorate at ASU. A few months after that conference, you applied for a fellowship with Cushwa and were among those invited to join us as postdoctoral research associates in 2020. Long story short, a global pandemic disrupted those plans, as Cushwa needed to pause a lot of its offerings, including our fellowships. Now, a year later, you’re finally joining us. Tell us a bit more about the past two years since you completed the Ph.D.

Jacqueline Willy Romero: I am more excited than ever to join Cushwa after the past year! My time since completing my Ph.D. has been spent balancing teaching and continuing my research for my book project.

My time in the classroom (both online and in-person) has reminded me of how important it is to continue to remain engaged in scholarship and to continue having conversations with both students and colleagues that promote understanding the complexity of history and historical actors. Gendered and racial dynamics continue to shape current events, and understanding how these dynamics can express themselves in different contexts is a key part of what I hope my students take away from my classes. I also make a point to expose my students to more “hidden narratives” in American history—after all, women religious were largely absent from historical research a few decades ago!

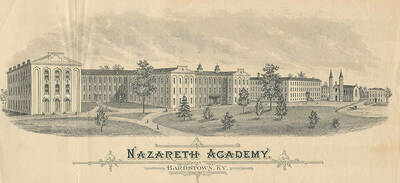

I have also been brainstorming ways to connect Catholic history as a subfield to broader scholarly audiences. Stephanie Jones-Rogers’ book They Were Her Property was published soon after I defended my dissertation; when I read it, I realized that it gave Catholic women’s history a powerful way to examine slaveholding. Since then, I have been expanding my research on sisters and slavery to bridge the gap between the two topics. My second article is currently in preparation and uses the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth as a case study to examine the relationship between white women, Catholicism, and slaveholding in antebellum Kentucky. I argue that slavery was not simply a passive background at Nazareth, but rather actively shaped the community’s actions and its relationships.

SU: Stepping back a bit—tell us more about your dissertation. How’d you arrive at the topic, what were some broader takeaways, and what’s your perspective on it two years later?

JWR: I began graduate school knowing that I wanted to pursue American Catholic history after I completed an undergraduate thesis on Catholic identity after the American Revolution. During my graduate seminars, I was introduced to women’s history and became certain I also wanted to incorporate that methodology into my research. Through conversations with my advisor, Catherine O’Donnell, I learned that many communities of women religious kept extensive archives that were not always well known to scholars, and that brought me to the two communities I focused on for my dissertation.

One main takeaway from my research is that communities of women religious produce a tension for historians to analyze: as celibate, educated women who used their skills for lifelong public service, they were clearly exceptional figures among 19th-century women. Yet they did not challenge the gendered hierarchies of their church. The nature of their agency does not fit neatly into the dichotomies of public and private power. I analyzed the relationship between obedience and autonomy to then connect that relationship back to gender.

Another aspect that is essential to both the dissertation and my book project is the importance of highlighting sisters’ interior lives. The history of women religious often focuses on their visible accomplishments—the institutions they established. Understandably so—they of course created and ran so many orphanages, hospitals, and schools. Such analyses often highlight the sisters’ achievements rather than their personal lives, and consequently lack clear attention to the role of spirituality. Although intangible in itself, religious faith produced tangible and material developments throughout the 19th century. Studying the intangible is challenging, but my research highlights the value of examining sisters’ personal letters and reflections to understand how they understood their relationship to Catholicism and how their faith shaped them.

Two years later, I am still struck by how dominant clerical sources remain in Catholic history. My primary goal was to prioritize and center sisters’ sources and voices themselves whenever possible, and I still often caught myself relying on a priest or bishop’s perspective without challenging their assumptions or digging into what might have been left out.

I am also always fascinated by how wonderfully human sisters can be, and how their personalities can shine through in their records.

SU: Can you give a few examples of sisters’ personalities that you found in the archives?

JWR: It’s hard to narrow my favorite examples down, especially because so many sisters had fantastic senses of humor, even (perhaps especially) in difficult circumstances. However, I think these (below) are particularly indicative of how even brief excerpts of sisters’ sources can reveal their personalities.

From a correspondence between a sister at the Nazareth Motherhouse and one of their branch missions: “We have so many new Sisters since you left you would hardly know old N. All-most all New-Yorks, you might suppose coming from such a distance, they were real beauties, but I declare, some of them make the big rats run.” When I first read this, it took me a moment to realize what that sister was implying!

A letter from Mother Catherine Spalding to another sister that gives such touching insight into the role of friendship within communities: “I wish I could give you gumelastic [sic] legs or some kind with which you could step even back to Nazareth for I assure you, I never did miss one so much in my life, & if the thing were to do over again, I believe I would not consent to it.”

Apparently not all sisters were able to keep up with their correspondences, as Mother Frances dryly remarks in one of her letters: “I had to open my eyes wide before I could believe I was really reading a letter from you, and sure enough it was a reality. Well, strange things will happen once in awhile.”

With those kinds of remarks in letters, I found it much easier to see sisters as unique individuals with their own personalities. It is also a reminder that so many personalities living together in community could not have been easy!

SU: You’ve also published an article in American Catholic Studies in 2019, “‘Scheming and Turbulent’: An Analysis of Obedience and Authority in the Founding of the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati.” Where do you see your research and writing moving in the year ahead (and beyond)?

JWR: In many ways, my article for American Catholic Studies highlighted how sisters like Margaret George decided to make moral choices in the face of conflicts with their superiors. Ultimately, Margaret decides that leaving her community to create a new one is a more moral choice than remaining in her original community under a new superior and new expectations. My most recent research puts increased focus on the sisters’ choices in the context of slaveholding. When communities owned enslaved labor, sisters actually became “superiors” in a sense. And they did not see owning human beings as immoral. Their mission of charity and benevolence did not extend to enslaved men, women, and children.

As mentioned above, I am currently preparing an article that utilizes the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth and analyzes how sisters owning slaves complicates and contradicts the image of their benevolence. This image grew from their dedication to serving anyone in need of assistance, from providing an education to poor girls, caring for an entire family of orphans, and even giving their lives in the course of nursing the sick during epidemics. However, much of this public service was possible only because sisters exploited enslaved labor for farming and domestic work.

The centrality of slaveholding to American Catholic history is an essential aspect of my book project as well. My goal is to examine a larger number of communities of women religious in the South, analyze their slaveholding history, and begin to address significant gaps in the historiographies of both Catholic and broader women’s history.

SU: We’re excited to finally have you with us at Notre Dame. The coming year will offer an opportunity to turn from teaching more to research. You’re on the program committee for the Twelfth Triennial Conference on the History of Women Religious and will be taking a lead in the planning for that. What are you most looking forward to in the year ahead?

JWR: I attended my first CHWR conference in 2019, and it was truly an eye-opening experience for me in the best way. Coming from a graduate program where I was the only student researching Catholicism, it was a completely new experience to be around so many other scholars who were interested in the same topics I was. Being a part of organizing and planning the next CHWR is high on my list of what I am looking forward to!

After the long year of COVID isolation, I am more excited than ever for an in-person CHWR in 2022. In general, I am certainly looking forward to once again being able to talk in person with colleagues to brainstorm research, learn about new developments in the field, and just generally enjoy academic and social interaction again!

Overall, I am really looking forward to immersing myself in a place that embodies American Catholic history the way Cushwa does. I have benefited immensely from its grants, conferences, and lectures, and am very excited to be a part of that mission.