James O’Toole is the Charles I. Clough Millennium Professor of History Emeritus and University Historian at Boston College. A scholar of Boston history and an expert on American religion and American Catholicism, especially the history of religious practice and popular devotional life, O’Toole was selected in summer 2020 to serve as one of the core researchers for the Cushwa Center project “Gender, Sex, and Power: Towards a History of Clergy Sex Abuse in the U.S. Catholic Church.” In August, Cushwa Center postdoctoral fellow Rev. Stephen M. Koeth, C.S.C., corresponded with O’Toole to discuss clericalism, priestly formation, Boston, and the place of clergy sex abuse within surveys of U.S. Catholicism.

Stephen Koeth: Since June 2020 you’ve been participating in the Cushwa Center’s “Gender, Sex, and Power” project (GSP), a group of 12 scholars researching various aspects of clergy sexual abuse in the U.S. Catholic Church. Tell us a little about the particular focus of your research.

James O’Toole: From the beginning of wide public awareness of clergy sexual abuse, many observers have identified “clericalism” as an underlying cause of the problem. Why had bishops and other Church officials been more intent on protecting abusers than victims? They seemed more focused on looking after the interests of fellow members of a kind of priestly club than on bringing justice to victims and bringing abusers to justice. A culture of clericalism was at the heart of the matter. No one could define clericalism, exactly, though many (myself included) thought they knew it when they saw it.

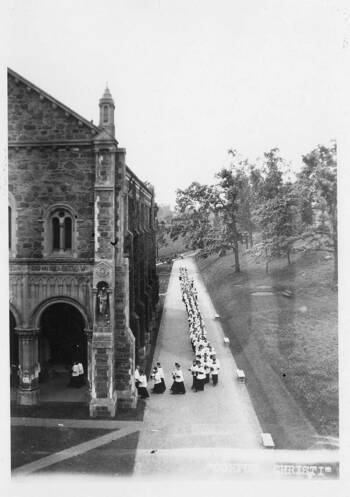

My project tries to get a handle on this by looking at clericalism in the specific case of the Archdiocese of Boston, home to some of the most egregious abusers. How had they been formed as priests? What definition of their role had been instilled in them? What sense of their own standing and privilege had they been encouraged to adopt, and how was that connected to their later abuses? My project is a case study of the clericalism produced in priests who had gone to Saint John’s, the archdiocesan seminary in Boston: How had they been initiated into this self-contained clerical culture?

SK: In a preliminary report on your research, you discussed how seminary manuals and a seminary’s rule of daily life were concerned with the character formation of seminarians. What qualities were the rector and seminary staff looking to inculcate in seminarians?

JO: Since the Council of Trent, seminaries have been conducted on what is fundamentally a monastic model. Strict separation from the outside world has been thought the best way to prepare priests to serve that world. Stating the matter this way sounds very odd, but that was the model. Seminaries are of course educational institutions (they have classes, exams, grades, academic degrees, and all the rest), but they are really more interested in producing—in “forming”—a certain kind of person. Their more important job, as they see it, is to instill attitudes, values, and ways of behaving as much as it is to impart knowledge. In Boston’s seminary throughout the first half of the 20th century, when the more serious abusers were there, these values included some of the following:

- Reserve: Strict outward control of the emotions and a stance of not letting other people, particularly lay people, get too close.

- Gentlemanly bearing: Maintaining a public face of distance and propriety at all times, regardless of one’s background or inner inclinations.

- Docility: Unquestioning obedience to superiors and Church authorities, even if that contradicted one’s own sense of self and duty.

- Serviceability: A willingness to go wherever sent, to do whatever assigned, and to suppress one’s own personality as needed in the process. Church leaders wanted to know, “Can we put this priest anywhere we need him?”

In the end, these and other values meant that priests were being formed to be of service to the Church’s people, but to do so from a position that was separate from and superior to them.

SK: You noted in your report how “the dynamics of supply and demand” apply to the priesthood as much as they apply to the business world. How, if at all, do you see surpluses or deficits in the supply of priestly laborers relating to the problem of clericalism and thus to the sexual abuse crisis?

JO: Until the 1960s, in Boston and elsewhere, there was a surplus of priests. In the 1930s, one archbishop in Boston dismissed 20 members of the seminary graduating class prior to ordination because he simply had no parish work for them to do. In the 1950s, another archbishop actively encouraged some of his priests to volunteer for work outside the diocese, particularly in Latin America, again because they would be underutilized at home. (In other dioceses, I know, bishops were deliberately sending their “problem” priests to work with racial and ethnic minorities in other parts of the country. Particular cases aside, Boston does not seem to have done this systematically.) As the number of vocations has fallen steadily since the 1970s, there has perhaps been a temptation on the part of some diocesan officials to be less choosy in whom they accept as seminary candidates. My own view is that, as numbers continue to decline, dioceses should become more exacting in selecting seminarians, not less.

SK: Thanks to the celebrated work of the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” team, people often think of Boston first whenever clerical sex abuse is discussed. In what ways is the Archdiocese of Boston unique in the history of clerical sex abuse and in what ways is it representative? How should scholars think about the similarities and differences between dioceses as they research clerical sex abuse?

JO: In 2002, Boston emerged as the public face of clergy sex abuse in the United States. There were many examples of particularly appalling behavior by abusers and of particularly bad leadership by archdiocesan officials there. But one of the things I have learned over and over in working with the other scholars who are part of this project is just how widespread these phenomena were. There were different local conditions and personalities from place to place, but offenders and bad leaders were everywhere. My project is a case study of how these clericalist attitudes and behaviors operated in Boston, but we also need to continue exploring cases from elsewhere. The more cases we study, the more we’ll know. The GSP project is doing just that.

SK: As part of the GSP project, the Cushwa Center has partnered with BishopAccountability.org to provide participating scholars with access to its previously unavailable archival sources on clerical abuse cases. Have any of these sources, and conversations with other participants, shaped your research?

JO: Working closely with BishopAccountability.org has been crucial for all of us in this project. As a former archivist myself, I am in awe of what BishopAccountability.org has accomplished in assembling and organizing documentation from around the country that would not otherwise be so readily accessible for study—or, indeed, accessible at all. In my own work, I am using those records to explore how the general phenomenon of clericalism operated in the cases of several of the worst abusers in Boston.

Our Zoom meetings over the course of the last year and a half have been crucial to our work as well. At times, we have (like the rest of the country) suffered from bouts of “Zoom fatigue,” but our discussions—both in the full group and in the several smaller sub-groups that formed—have always been stimulating and helpful. While this has helped keep the project moving, I am looking forward to our meeting in November.

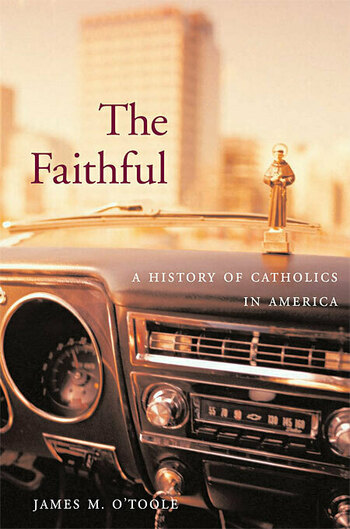

SK: Your splendid survey, The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America, was published by Harvard University in 2010. How, if at all, would you update or revise that work in light of your current research on clericalism and sex abuse?

JO: The Faithful was written in the immediate aftermath of the exposure of widespread sexual abuse, and it was intended to provide historical context for understanding how Catholicism in America had gotten to that point. In particular, at a time when the voices of lay people in the Church, demanding accountability and change, were so insistent, it seemed useful to try to reimagine American Catholic history. What would the history of the Church look like if we approached it as a story not of bishops and institutions, but of ordinary Catholic lay people—the people who filled the churches on Sunday mornings; the people who sent their kids to parish schools; the people who were helped by Church-affiliated social service agencies?

The full dimensions of clergy sex abuse were still emerging at the time I was writing the book and now, almost 20 years later, there would be more detail, more reflection on the relative significance of particular factors. The ongoing work of scholarship, as embodied in the GSP effort, will help move us toward those deeper understandings. And that, we can hope, will also bring us to greater care for victims and more effective means of preventing abuse in the first place.

SK: You’ve also been working on a project exploring the practice of confession in America. Are you seeing any connections between that project and your work with GSP?

JO: For the last several years, I have been working on what I call a social history of the practice of confession. For generations, American Catholics went to confession in huge numbers; they didn’t always like to do so, but they did it anyway as a marker of their religious identity. And then, in the 1960s and 1970s, the practice of confession simply collapsed. Even those who continued to identify as faithful Catholics went to confession seldom or not at all. The central question I’m exploring is why that happened, and there are many reasons, both internal to the Church and external from larger changes in American society.

As for the specific relationship between confession and sexual abuse, several links have become clear. First of all, we know that many abusers used confession to groom potential victims, and we know that some abuse actually occurred in the confessional itself. It is also noteworthy that many abusers took advantage of the “seal” of the confessional to cover up their crimes, deliberately misleading victims into thinking that the requirement of secrecy in confession applied to them rather than to the priest-abuser. Terry McKiernan of BishopAccountability.org is working specifically on confession as part of the GSP project, and he and I have had many fruitful conversations.

SK: What are the next steps for your own GSP research? Do you see any promising avenues of inquiry that future scholars might want to explore further?

JO: As I’ve said, my paper will focus on the development of clericalism in Boston and how those attitudes played out in the lives of several of the serial abusers, and I plan to submit this paper for publication in an appropriate journal. I also look forward to the presentations and discussions of the conference at Notre Dame, which will help sharpen the analysis. More broadly, I hope that examination of this topic will spark more interest in studying the history of the American Catholic priesthood. Curiously, priests have been largely overlooked in existing scholarship. We know a great deal about bishops and increasingly about women religious and about lay people. We need to know much more about priests: their backgrounds, their daily and weekly working lives, their successes and failures, their impact on the Church and its people.

Rev. Stephen M. Koeth, C.S.C., is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center.

This interview appears in the fall 2021 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.