Lifeblood of the Parish:

Men and Catholic Devotion in Williamsburg, Brooklyn

Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada (New York University Press, 2020)

Review by Jacqueline Willy Romero

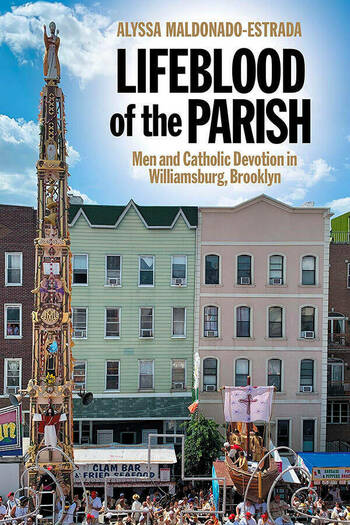

The annual celebration of the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and San Paulino of Nola (St. Paulinus) in Williamsburg is one of the most public Catholic displays in the United States, stretching over 10 days and bringing with it large crowds, vivid sights and smells, and a deep connection to the Italian American history of the parish and surrounding neighborhood. The festivities and their attendance stand in contrast to the frequent characterization of Catholicism in the United States as struggling, declining, or in crisis. Underneath the liveliness and the prominent celebrations, however, is a network of dedicated parishioners who devote significant time and effort to continuing this longstanding tradition. In Lifeblood of the Parish: Men and Catholic Devotion in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada focuses on the group of men, young and old, who carry the feast on their shoulders.

Coordinating and executing the logistics of the feast require a multitude of roles and responsibilities: managing finances, food and drink, rides, and devotional materials; monitoring and cleaning the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (OLMC); and advertising the feast’s presence and history. The two main events consist of the procession of Our Lady, carrying a statue of the icon, and the much-anticipated “Dance of the Giglio.” Involving a massive, tiered spire and a boat carrying a victorious “Turk,” the peak of the spectacle is “the lift,” where more than 100 men take the two objects on their collective shoulders and move in coordination, directed by their chosen leader, or capo, a role exclusive to men. Maldonado-Estrada analyzes how this masculinity is constructed and maintained through preparing for the festival each year. The lift is both a culmination of a year’s preparation and a display of physical and emotional devotion that produces Catholic manhood.

As a case study, Lifeblood of the Parish sheds light on a group of Catholics often not visible in historiography: lay men. Her focus on masculinity, male bodies, and labor encompasses the entirety of this feast as a “public devotional spectacle,” in contrast to previous ethnographies illuminating the private devotional practices of women (39). Devotion to the feast, and the importance of lifting the Giglio in particular, is not only visible during the 10 days of its official celebration. So important are feast symbols to the men who devote their bodies to creating and carrying them that many mark them permanently through tattoos. Making the case that tattoos can be considered sacramentals just as much as statues and scapulars, Maldonado-Estrada argues that the tattoos demonstrate not just a relationship to a particular saint but also to other men. They demonstrate men’s commitment to the feast and, simultaneously, their commitment to laboring with other men to ensure the feast’s continuity. By spotlighting these homosocial relationships, Lifeblood of the Parish fills a clear gap in Catholic devotional historiography by demonstrating that lay men can and do have devotional lives.

The devotional lives of OLMC parishioners are often tied to family, particularly children. Research on women’s devotion also highlights the role of wives and mothers as caretakers essential to maintaining family relations. The male feast organizers see their role as one of a role model, involving their children in the feast at a young age and ensuring they are exposed to the types of labor necessary for a successful feast. The event of the children’s lift introduces young children, especially boys, to the tradition as early as possible. This early exposure encourages the idea that lifting is innate, or “in their DNA” (68–70). Boys in particular are considered essential to the feast’s continuity; girls are “phased out” as they get older and encouraged towards more behind-the-scenes work of the feast, rather than the public displays of lifting (73). This clearly defines separate expectations for boys and girls, setting the foundation for the public and private divide between men and women’s devotions.

In Lifeblood of the Parish, meaning is made through process rather than any finished product: “The focus here is on production as a religious act rather than the use of already-complete objects in religious acts” (76–77). And outside the lift on the day of the feast itself, most of the process of meaning-making happens in the basement. Conceptualizing this space as “an ecosystem,” its containment of multiple roles and processes makes this single area ripe for multilayered analysis (43). Further characterizing this ecosystem as “subterranean,” Maldonado-Estrada argues that “the values and rules that govern interactions in the basement are different from those ‘upstairs’” (77). Her insight into these boundaries and how they are constructed is a result of her role as an immersed ethnographer.

Entrance to the basement and the process of being accepted as one of those “below” was contingent on Maldonado-Estrada’s dedication to a wide variety of labor, being willing to work at any task deemed necessary. Through undergoing this “enskillment” of painting, repairing, and constructing, she was able to observe the “tiers of deference and respect” that governed roles in the basement ecosystem (102, 89). Maldonado-Estrada is upfront about being a woman in a largely men-only environment, raising intriguing questions concerning the influence of gender in ethnographic settings. Ultimately, she concludes that she “found gendered boundaries to be strikingly more flexible than I had imagined,” with the value of her labor compensating for her outsider status. Still, gendered expectations did not disappear entirely, as she notes the men also felt that she was to be cared for as they cared for other women involved in the feast traditions (102–104). Her transparency regarding her ethnographic methods serves as a reminder that ethnography is a dynamic process; her participation shaped her subjects and the feast, while being immersed in the feast world also influenced her perspective and her arguments.

Outside preparing the Giglio and practicing as lifters, OLMC men organize other logistics to ensure a successful feast day. What constitutes success is multifaceted, but foundationally the feast should financially support the parish for the upcoming year. Fundraising and finances are the “life and death of the parish,” a reality not only in Brooklyn but most parishes throughout the United States (107). The centrality of financial health and reliance on the feast day are what lend the book its title, as Maldonado-Estrada explains “when pastors refer to the feast as the lifeblood of the parish, it is a metaphor that not only speaks to vitality, life, and survival but also evokes families, lineage, bonds, and bloodlines” (111). Calculating the profits after a feast day is a pivotal moment; one year’s exceptional sales resulted in exclamations of “Holy shit, holy shit, this year we made $8,158 on beer, and last year only did five grand, holy shit” (126). This enthused money counter, who holds an MBA, tells Maldonado-Estrada that he believes he got his degree so that he could be a central figure in the feast’s financial organization. His enthusiasm and feeling of fate in connection to the feast reflect the significance that OLMC men assign to their contribution in hopes of collective success.

The relationships between these men offer what Maldonado-Estrada identifies as a “ripe site of homosociality” (98). In a hierarchy fitting of a deeply structured institution like Catholicism, becoming a capo puts a man at the top of the ranks. Obtaining this title—the most honored man involved in the feast—requires decades of time, labor, and experience, especially giving one’s body to being a lifter. Although it requires great physical dedication to earn, Maldonado-Estrada argues the title is an archetype in itself, “the pinnacle of feast manhood” (143). These relationships cannot be formed and function as necessary without the context of an assumed heterosexuality, one that permits participants to accept the embodiment and physicality of lifting the Giglio—the “proximity, touch, contact, and mutual support” required to do so (168). The cost of challenging this is high, as Maldonado-Estrada explains through the experiences of Anthony, a gay man. His story of exclusion from the feast and lifting after publicly marrying his same-sex partner shows that to lose that presumed heterosexuality is essentially to lose one’s status in the feast community, even if the previous status was highly revered.

Although the focus is on an Italian American ethnic parish, Maldonado-Estrada contributes an important addition to the historiography of race, particularly in urban Catholicism. The men of the feast make it clear that the continuity of the feast traditions is vital, encouraging passing the traditions down to their children by involving them in feast organization from a young age. However, the increasing presence and attendance of Haitian Catholics at the feast have raised questions about who the feast “belong[s]” to and what is needed for its survival in a nation where Catholicism is becoming increasingly less white (177–78).

Maldonado-Estrada is not the first to analyze the increasing number of non-white Catholics, particularly in New York City, but she does persuasively reinterpret the relationship between Haitians and Italians at the shrine. While Robert Orsi has characterized Puerto Ricans as excluded by Italians from the feast, he also argues that Haitian presence as pilgrims did not create significant anxiety for Italian organizers. Elizabeth McAlister argues that Italians were not threatened by Haitian presence at the feast largely because Italians continued to control the shrine and feast activities, while the Haitian role was only to “consume.” Maldonado-Estrada complicates these narratives by arguing for Haitians as a “discursive foil”; although devotional coexistence can be found, the feast is also a site of “racializing, territoriality, and boundary making” (172–74). Although in many ways Italians are thankful for the Haitian dedication to the shrine and feast activities, aside from their financial contributions, they prefer to keep them at a distance.

Racist language, including “swarming,” “superstitious,” and multiple references to “voodoo,” permeates the conversations Italians have with Maldonado-Estrada when discussing Haitian devotees. These same conversations also describe Haitians’ faith as “real,” “true,” and “beautiful,” demonstrating the pervasiveness of what Matthew Cressler has identified as “romantic racialism” (178–79). One of Maldonado-Estrada’s strongest analytical contributions is making the connection between these dehumanizing, generalized statements made against Haitians to the initial criticism and distrust of Italian Catholics new to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Then, clergy members (most often Irish) were often critical of Italian feast days, characterizing them as superstitious and preferring to keep the influx of new devotees at arms’ length.

Now, as those in control of the parish and its feast, Italian parishioners and Brooklyn residents are those in position to demarcate their boundaries of accepted behavior and identify threatening outsiders. As Maldonado-Estrada and many of the parishioners acknowledge, Haitians are vital to maintaining successful feasts; they are inextricably tied to its financial success, as “they come, they people the shrine, Masses, and processions, and they spend money on candles and give offerings to the ribbon” (186). However, their presence is still considered a change that Italians did not ask for and yet are forced to grapple with. To deal with this change, they have adopted a declension narrative that Maldonado-Estrada eloquently analyzes as “constructing a past where they were not outnumbered but plentiful” (187). By characterizing the intensity of Haitians’ devotions, they are at the same time lamenting the fact that, though they still largely control the feast, they are not as devoted as they “used to” or “could be.” This struggle to regain a lost dedication to the faith reflects a broader trend in American Catholicism as parishes face mergers and many churches struggle to maintain members.

One of the most impressive aspects of Lifeblood of the Parish is its ability to analyze and connect multiple complex topics such as gender, race, devotionalism, and urban spaces. Although each is treated diligently, some readers may find themselves wishing for a more in-depth treatment, perhaps even an entire monograph, of the evolution of race in urban parishes like the Shrine of Mount Carmel. The influence of an increasing Hispanic population in the United States has become a larger topic of study in American Catholicism, but further attention to other marginalized groups such as Haitians would help ensure race becomes a central point of study for the field.

As the book progresses, subsequent chapters shift away from the initial focus on masculinity and manhood towards race and intra-Catholic boundaries. This progress gives the book its impressive breadth of scholarly contribution, and Maldonado-Estrada more than meets her goal of spotlighting the OLMC men. There are still several moments, however, where women or girls are mentioned on the fringes of male activities, or “behind the scenes” (9). Their presence hints at the potential for future scholars to investigate what role women might have in reinforcing and encouraging markers of manhood, both at the feast and in other contexts. Ultimately, Lifeblood of the Parish provides a much-needed look into the devotional lives of Catholic men and the shifting role of ethnic parishes, two crucial topics for understanding the quickly changing contemporary American Catholic landscape.

Jacqueline Willy Romero is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center.

This review appears in the spring 2022 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.