In April 2023, Notre Dame’s College of Arts and Letters announced that Darren Dochuk and David Lantigua would take up new leadership on campus as the William W. and Anna Jean Cushwa Co-Directors of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism, succeeding Kathleen Sprows Cummings after her 11-year tenure as director. Like Cummings, Dochuk and Lantigua both earned their doctorates at Notre Dame. Their co-directorship began in July. In August, Philip Byers interviewed them about their graduate training at Notre Dame, teaching and research, and initial thoughts on their new roles at the Cushwa Center.

Philip Byers: The Cushwa Center’s last director and new co-directors all completed doctoral work at Notre Dame. Tell us about your time as a graduate student here—mentors, key experiences, and how this place formed you for the start of your career.

Darren Dochuk: I arrived at Notre Dame’s Department of History in the late 1990s with aspirations to work with the leading scholar of American evangelicalism, George Marsden. At the time, I knew very little about the department’s graduate program other than that it specialized in religious history. Happily, once I settled in at Notre Dame, I realized that the program encompassed so much more than the study of religion and that it was populated with scholars who studied the intricacies and entanglements of religion in broader swaths of social, cultural, economic, and political history.

One of the first “ah-ha” moments for me came while taking course work with John McGreevy, who—as a “youngish” professor new to Notre Dame—had just published his first book, Parish Boundaries: The Catholic Encounter with Race in the Twentieth-Century Urban North (University of Chicago Press, 1996). McGreevy parsed out the manifold ways that theology informed Catholic activism both for and against civil rights and social reform in northern cities like Chicago. His focus on the Catholic parish as a physical and political as well as theological construct and analysis of how Catholics’ notions of parish and neighborhood space made them more eager than Protestants to stay and fight change in their communities—be it driven by in-migration of Black homeowners or practices of blockbusting carried out by realtors—opened my eyes to a method of religious history that was much more expansive than the narrower sort of “church” history I had been enamored with up to that point.

Marsden and McGreevy became lead advisors on my committee, and under their direction I wrote a dissertation that examined the intersections of religion, region, and grassroots politics with focus on the conservative side of the spectrum. Back in the early 2000s, when I was chipping away at the thesis, historians of the modern United States were just starting to pay attention to the rise of conservatism and the Republican Right. I set out to engage this literature by writing about post-Depression/post-World War II southern migration to Southern California, and specifically about the role transplanted “plain folk” religion and populist politics played in generating the “Reagan Revolution” that California experienced in the late 1960s, a decade before the phenomenon went national. Bringing their own expertise to my dissertation committee were Gail Bederman, a leading cultural historian who pressed me for deeper analysis of the social conservatism my subjects defended, and Walter Nugent, a leading historian of populism whose sharp eye for political nuance and historical detail helped me make sense of the populist impulses of modern conservatives and kept me honest in the archives.

I also had the good fortune of being able to study on a campus where, thanks in no small part to the Cushwa Center and its Seminar in American Religion, I was constantly introduced to the leading scholars and scholarship in modern U.S. religious history.

All that is to say I feel like I lucked into a special situation at Notre Dame. Besides benefitting from a committee that was so well balanced and well tuned to my project, I also had the good fortune of being able to study on a campus where, thanks in no small part to the Cushwa Center and its Seminar in American Religion, I was constantly introduced to the leading scholars and scholarship in modern U.S. religious history.

PB: Describe your path from graduation back to the Notre Dame faculty. Where else have you worked, and what convinced you to return to campus?

Darren Dochuk: My first venture beyond Notre Dame was a postdoctoral fellowship at Valparaiso University. I was then offered a tenure-track position in the Department of History at Purdue University. I felt incredibly fortunate to join the Purdue faculty right out of my Ph.D. and to find myself in a first-rate institution that supported research as well as teaching and a welcoming community that made life beyond the academy so easy and enjoyable. My wife and I developed several lasting friendships during our seven years in West Lafayette. Alas, in 2012 I was asked to join the faculty of the brand-new John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis. We jumped at the chance to be part of this innovative and exciting center and to set down some roots in St. Louis, a city full of beautiful parks and historic neighborhoods, a thriving food scene and arts. Wash U, the Danforth Center, and the university’s history department gave me every opportunity to excel as a teacher and writer, and I truly cherished the chance to work with so many talented scholars and generous people, many of whom remain good friends.

It turns out that the “roots” we set down in St. Louis never ran deep. In 2015 I had the opportunity to return to Notre Dame to help shore up the Department of History’s strengths in U.S. religious history and modern U.S. history broadly. While it was a bit surreal at first to be comparing notes with colleagues who once quizzed me at my dissertation defense, the adjustment was not difficult: in some ways it felt like we had never left South Bend and Notre Dame. To be sure, both had continued to evolve since my stay here as a graduate student. But this town and this campus are unique. It is particularly gratifying to be able to research and teach matters pertaining to religion at a place where matters of faith are taken seriously, as worthy of engagement and interrogation, study and service. Another feature of my graduate student experience has remained constant as well: the centrality of the Cushwa Center to the intellectual and communal makeup of this university, which is why it is such an honor to help lead its next steps.

PB: What have been your major research interests in the past, and what are you working on presently?

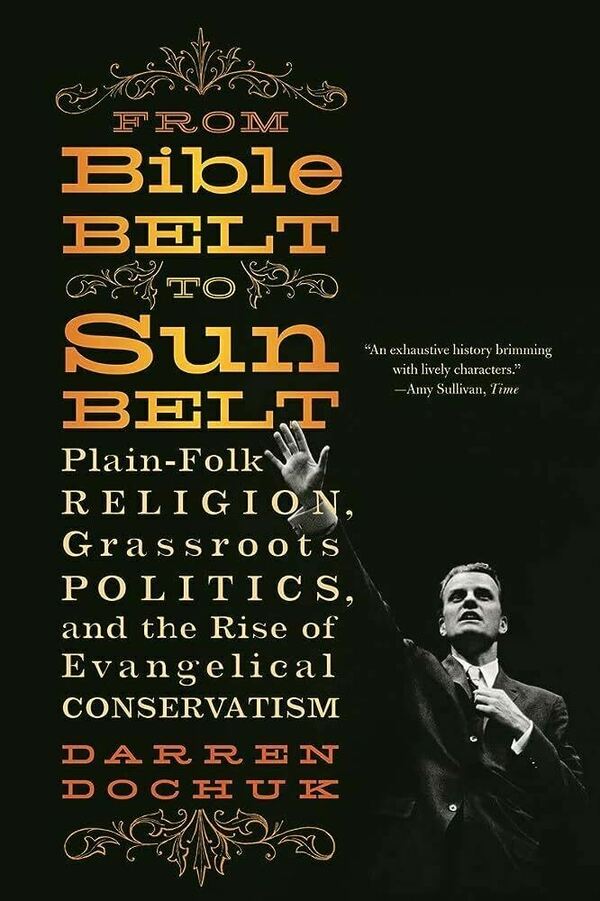

DD: My dissertation was revised into a book titled From Bible Belt to Sunbelt: Plain Folk Religion, Grassroots Politics, and the Rise of Evangelical Conservatism (Norton, 2011). The book tracked the ascent of southern evangelical institutions and influences in post-war Southern California, both as a force of change within the pulpits and pews of California and as a dominant presence within the emerging conservative movement that gained its initial success with Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign in 1964, then more lasting success with Reagan’s election as California governor in 1966 and his run at the White House in 1980.

After the book’s release I continued to write at the intersection of religion, politics, and region, though with increased interest in energy and environment. While conducting research for From Bible Belt in Texas and Oklahoma I came to appreciate the outsized role that petroleum had played and continued to play in local religious life. Wherever I drove, it seemed, I would see a church steeple in one corner of the eye, an oil pumpjack in the other. I wondered what would happen if I wrote about these two entities in one single historical narrative. How has the oil industry and oil itself shaped the American religious imagination, facilitated the growth of religious institutions, and fueled religious outreach at home and abroad in the modern era? How, in return, have the teachings and functions of “the church” (be it Catholic or Protestant or non-Christian) reinforced the prerogatives of the petroleum sector and legitimated the extraction and dependencies of the black stuff? With what burdens and expectations for the nation writ large? I tried to tackle these (and other) questions in Anointed With Oil: How Christianity and Crude Made Modern America (Basic, 2019).

I continue to explore the connections between religion, politics, energy, and environment in North American as well as global contexts. Two book projects are keeping me busy at the moment. One uses the late 1970s energy crisis and Jimmy Carter’s moralistic response to it as a launch into a longer “moral history” of energy in American life. In essence I am asking questions about the relationship of faith and energy that mirror the ones I probed in Anointed With Oil—but with a wider gaze on other energy systems, including nuclear, coal, hydro, and electric. A second project is nearer completion; it is a quirky but fun (and instructive) microhistory of a lake and a town in Cold War Southern California. Elsinore, California, was a cosmopolitan place circa 1940—a place with a vibrant civil society defined by its religious pluralism. Situated on the shores of Lake Elsinore, the largest natural lake in Southern California, Elsinore was an annual destination for hundreds of thousands of vacationers, as well as home to several thousand Protestants, Catholics, and Jews. But when, due to shifting weather patterns and hotter and drier conditions, the lake dried up in the early 1950s, this model community unraveled. A decade-long period of religious and political extremism followed. Only when the state agreed to refill the lake in the mid-1960s were peace and civil society restored. The years of Elsinore’s trial and tribulation thus serve as a clear window into the challenges, including religious, local citizens face when the winds come, the water recedes, and climate change creates crisis.

PB: Outside responsibilities in the history department, what are some other ways you’ve engaged on campus and beyond?

DD: One piece of advice I regularly offer graduate students at Notre Dame is to be careful not to commit to too much. This is a lively campus, one where so many occasions for learning and engagement arise and entice on a weekly, even daily, basis. Whether it be at the departmental level or through the offerings of various centers and institutes on campus, this is a place that affords students and faculty an abundance of opportunities to connect with peers across disciplines and to process new ideas, and that is certainly a good thing—provided one maintains a healthy pace.

My own professional development has benefitted greatly from investment in some of the campus’s interdisciplinary offerings. My affiliation with the Kroc Institute has been highly rewarding, as it has allowed me to work with graduate students in Peace Studies whose scholarship seeks to apply lessons of the past to very current global crises. My work with ND Energy has been edifying as well. During the past few years, I have been able to teach a course on the history of energy in American life, supported by ND Energy and the sustainability studies program; it has been such a privilege to teach non-history majors whose career paths often take them into the energy business. My hope is that the humanities perspective I bring to the study of energy is something they will take with them into their professions, allowing them to see the moral as well as material, cultural and economic dimensions of energy systems and their place in our society. Finally, I would say that one of the most important communities of scholars I have invested in over the years is CORAH (Colloquium on Religion and History), a bi-weekly workshop group of roughly 15 to 20 faculty and graduate students who gather to discuss each other’s work. CORAH was active when I was a grad student and so critical to my scholarship’s development. While my role at Notre Dame has changed over the years, the generative qualities of CORAH remain, its contributions to my writing every bit as critical as they were 20 years ago.

I also remain engaged with colleagues and friends beyond Notre Dame’s borders. Notre Dame is generous in its support of our research and writing, which makes me all the more committed to helping my wider historical guild. One of my current priorities in that respect is serving as co-executive editor of Modern American History, a major journal in the field of 20th-century U.S. history published by Cambridge University Press. Known as one of the most innovative journals in the business, MAH provides historians with the chance to write provocative think pieces as well as traditional research articles, all in an effort to advance our thinking and teaching in U.S. history. And for our purposes, the journal’s placement here at Notre Dame for the next four years means that history graduate students, many of whom benefit from affiliation with Cushwa, can gain additional exposure to and training in academic publishing.

PB: You and David Lantigua will have more to say in weeks and months ahead regarding your visions for the Cushwa Center’s future, but for now, what are some initial thoughts as you take up leadership here?

DD: Our own personal histories with the Cushwa Center mean we are stepping into the co-director role knowing how vital this institution is, not just for those on campus but for scholars of American Catholicism and religion across the globe. As a team, we look forward to fortifying Cushwa’s engagement with questions of gender and Catholicism, its sponsorship of archival research and cross-disciplinary collaborations in Rome, the Seminar in American Religion, and the rich variety of lecture series, grants and awards, and postdocs. All of these initiatives remain a priority for us as we look to keep Cushwa at the center of the action where understanding modern American Catholicism and modern American religion as a whole are concerned.

I am anxious to build on these ties and connect Cushwa to other units on campus, those housed in the sciences and business as well as humanities—a cross-section of communities that I am trying to engage with my current historical scholarship on energy, environment, religion, and political culture.

We are also excited to integrate new emphases in the center’s programming. While David’s commitment to the Cushwa Center is very much driven by his interest in continuing to expand its purview to include more historical and contemporary focus on American Catholicism’s racial/ethnic diversity and global footprint, I hope to bring an “ecumenical” spirit to the center by seeking to embed histories of particular faith traditions in wider narratives of societal change. Cushwa has always been a place for ecumenical connection; scholars of all faiths have long looked to it as an epicenter of exchange, and we want to fortify that reputation. In my case, I am anxious to build on these ties and connect Cushwa to other units on campus, those housed in the sciences and business as well as humanities—a cross-section of communities that I am trying to engage with my current historical scholarship on energy, environment, religion, and political culture. Similarly, I would also love to place Cushwa in conversation (even collaboration) with like-minded centers across the country—places such as the Danforth Center, Clements Center for Southwest Studies (SMU), and Princeton’s Center for Culture, Society, and Religion. And as a whole I want Cushwa to be integral to the ongoing conversation in the Catholic Church (inspired by Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato Si’), among religious communities of all stripes, and within a general citizenry about our past and present grappling with faith and energy in human and natural environs and about the way we might envision earthcare in the future.

In all these different facets of our vision, we look forward to “synergizing” our work as co-directors to reflect an interdisciplinary, transnational, and ecumenical study of American Catholicism in view of the global Church and to create a truly dynamic meeting place where scholars of wide disciplinary backgrounds and a diverse public can converge to dialogue and collaborate.

Philip Byers was a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center from 2020 to 2023. In August, he was appointed the Halbrook Chair of Civic Engagement at Taylor University.

Read Byers’ interview with David Lantigua.