Are American Catholics on the verge of getting a new saint of their own? And what can historians learn from the process of an unlikely man going from material rags to spiritual riches?

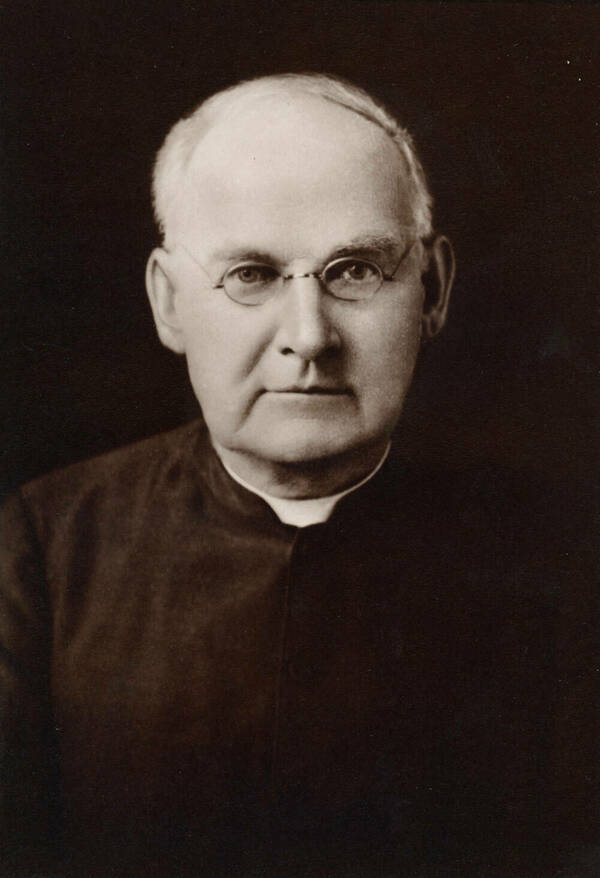

John O’Neill was born in November 1848 in the coal mining town of Mackeysburg, Pennsylvania. A “congenital foot abnormality” precluded O’Neill from participating in the industry that employed most local men, so he took up work with the town cobbler and learned the shoe trade. Eventually he left Mackeysburg, working his way across the country westward as an itinerant cobbler, spending significant periods of time in Colorado and California. During his travels he learned about the trades education offered by the Brothers of Holy Cross at the University of Notre Dame; acting on a longstanding but as yet unarticulated sense of vocation to religious life, O’Neill wrote to the University. Correspondence turned into meetings with the religious congregation’s novice master and Father Edward Sorin, founder of Notre Dame. O’Neill entered the novitiate for the Brothers of Holy Cross in September 1874, taking the religious name Columba. Thus began O’Neill’s decades-long “dual career”—as cobbler to the Notre Dame community and those the Holy Cross fathers served and as a man renowned for the apparent efficacy of his prayers for those in need.

O’Neill longed for a far-off assignment, offering to go to India or to work with now-Saint Damien De Veuster, the Belgian priest who spent the last 15 years of his life among those suffering from Hansen’s disease on Moloka’i. Instead of a posting in the Pacific, O’Neill was placed at St. Joseph’s Orphan Asylum in nearby Lafayette, Indiana. He served the children there for six years, returning to Notre Dame in 1885. As his biographers have written, “not much happened” for this “brother living a simple life, praying in secret, making and repairing shoes. He seldom stepped foot outside of Notre Dame, except for occasional visits to his sister Eliza’s parish, St. Mary’s in Keokuk, [Iowa].”1

O’Neill’s role as cobbler to Notre Dame occupied much of his time for the next three decades. He also spent two years as caretaker to the aging Father Sorin, until Sorin’s death in 1893.

Even while O’Neill kept the young men of the school and the Holy Cross community well shod, he built a reputation for great holiness elsewhere. He began and maintained an industrious operation of crafting and distributing small devotional badges depicting the Immaculate Heart of Mary and the Sacred Heart of Jesus; he claimed to have made about 10,000 of the former and 30,000 of the latter over the course of his life.2 He also kept up a voluminous correspondence connected to this devotional operation. Through this correspondence—which includes over 10,000 letters written to him, archived today by the Midwest Province of the Brothers of Holy Cross—O’Neill carried out a ministry of prayer for decades, connecting to men and women across the United States who contacted him in need of prayer for a wide variety of problems and crises.

O’Neill died at Notre Dame in November 1923 of long-term complications from influenza, which he had contracted during the postwar pandemic. At the time of his death, he had already secured a reputation as a man of great simplicity and deep holiness. An oration delivered at his funeral by Holy Cross priest Charles O’Connell made clear the utter plainness of O’Neill:

To the eyes of the world we gather merely about the mortal remains of an old man whose life was of no great moment, no special service to his fellowman. His no distinction of birth, or wealth, or education, as the world sees it. He wrote nothing, he discovered nothing, he invented nothing, he contributed nothing to the progress of mankind.

Yet of this man who had “contributed nothing,”

His name was known to thousands . . . the notice of his death is carried by the public press throughout the land, and the religious family of which he was a member unites to give him all the honor within our power to bestow. For the past two days the faithful in a constant stream have approached his bier and touched their rosaries and medals to his hands, or stood in rapt devotion, looking at his plain and peaceful face.3

A hundred years later, Brother Columba’s religious congregation would once more attempt “to give him all the honor within our power to bestow.”

The Brothers of Holy Cross are seeking a saint.

Saints for the Church and for Holy Cross

How did utter mundanity come to be paired with great sanctity? And why should historians, especially those not within the Catholic tradition themselves or those working on topics beyond Catholicism, give attention to the internal system of recognizing sanctity that is unique to the Catholic Church? The very existence of such a process has long been a point of significant theological friction between Catholics and non-Catholic Christians. Catholics historically have been (and still are) accused of “worshiping” saints, seen by some as an act of blatant idolatry. But in the internal logic of Catholic theology, Catholics pray to—not worship—those they believe to be in the presence of God. They believe these men and women to be advocates, not unlike themselves, who can represent the living in a way otherwise impossible. Furthermore, those who pray to the saints view the process as little different from asking a friend to pray for some need—it just so happens, as Catholics believe, that these “friends” have already left their earthly lives. Historians of religion would do well to attend closely to this nuanced relationship between living human beings and the afterlife, a relationship understood by the largest proportion of the largest religion of the world to be built on a scriptural foundation. But there is a significant difference between persons an individual Catholic might think can intercede for them with God and those the Church has formally named as saints. And gaining recognition as a saint is no easy process.

The road to sainthood is long, complicated, and costly for those who support the prospective saint, and it never has an assured destination. There are multiple criteria that must be met as the individual in question progresses through several stages. Within the Roman Catholic legal structure, once the competent local authority—in most cases, a diocesan bishop—consents to begin the process of researching and investigating the person for canonization, the person is given the title “Servant of God.” From there they may progress through “Venerable” and “Blessed” until—if the cause is successful—they become “Saint.”4 Importantly for historians of religion, the Catholic Church does not presume to have done anything by declaring a person a saint. Instead, as Kathleen Sprows Cummings notes in her 2019 book, A Saint of Our Own,

In the eyes of Catholic believers, canonization reflects a truth about an individual’s afterlife in its literal sense. In raising a candidate to the “honors of the altar,” the church affirms that the saint, having practiced certain virtues to a heroic degree, passed immediately upon death into the company of God and all the saints, where he or she is an advocate for and inspiration to the faithful on earth.5

In other words, canonization is neither more nor less than an acknowledgement of an existing state of affairs. Catholics do not believe canonization somehow “promotes” a person to heavenly bliss; instead, canonization adds the person to the list—or canon—of those the Church has formally acknowledged as being in that state.

Why was O’Neill’s name “known to thousands,” as O’Connell put it? And what sources remain for historians to learn more about him?

Today, the Brothers of Holy Cross are working hard to gain that recognition for Columba O’Neill. That project must answer a key question: Why was O’Neill’s name “known to thousands,” as O’Connell put it? And what sources remain for historians to learn more about him? Researching a figure like O’Neill presents certain challenges. While he was of intense interest to those who sought his prayers and to others in the Catholic world, his fame did not rise to the level of a contemporary religious figure like Billy Sunday. He made several appearances in the South Bend Tribune, the newspaper local to Notre Dame. An April 1916 article on a shrine to the Sacred Heart that O’Neill established in Notre Dame’s historic Log Chapel mentioned “the many apparently miraculous cures that are continually being wrought through Brother Columba.”6 Upon his death in November 1923, the same paper called him a “miracle man” and noted that “many of his clients loudly proclaimed that they were cured through his ministrations and assistance.”7 With significant interest in the Catholic Church’s process of canonization, the Tribune reported in 1934 that O’Neill could “become Notre Dame’s first saint,” and that “in all weather pilgrims are seen to be kneeling at his grave.”8 The paper reported that “many times cures for cancer, tuberculosis of the bone and other maladies were attributed to his intercession.” Yet so much interest from a secular newspaper was the exception, and probably due to the University’s location. While he appeared more frequently in the Catholic press and was described there in terms familiar to Catholics, Columba O’Neill was not a household name for most Americans.

But to his many correspondents, O’Neill’s importance was unquestionable. One cannot pore over the thousands upon thousands of letters written to Brother Columba without suspecting that some petitioners attributed healing to the man directly. Yet he made no such claims himself, and therein lies the core of Brother Columba’s potential as a saint. It was his seemingly unceasing prayer, made over the course of an otherwise unremarkable life, that set O’Neill apart. In a formula typical of 19th-century American Catholic devotion, O’Neill attributed whatever good resulted from requests made of him to his prayers “to the Sacred Heart of Jesus through the Immaculate Heart of Mary.”9 The simple cobbler prayed for whatever need someone may have mentioned, “and he expect[ed] cures because of his ‘child-like’ faith.”10

I asked the petitioner for Brother Columba’s cause, Brother Philip Smith, C.S.C., an archivist in the Midwest Province of the Congregation of Holy Cross, what it was about the man that could advance O’Neill’s canonization. “No one was turned away, especially non-Catholics,” Brother Philip told me. “He was an ordinary man, with a profoundly simple prayer life, utterly focused, like so many others in the early 20th century . . . intent on using his skills for the better of self and community.” O’Neill’s lack of erudition and dedication to prayer come out in a typical letter written to a priest in October 1912: “I will pray for the sick girl all so. You give her a badge to ware and tell her to say Sacred Heart of Jesus cure me 5 times a day for a while . . . offer her cure thru the Blessed virgans heart.”

A rich repository

Fortunately for historians with generous archival colleagues, the process of advancing an individual for canonization involves collecting an enormous amount of source material. The archival materials on Brother Columba are held at the administrative offices of the Brothers of Holy Cross Midwest Province in Notre Dame, Indiana. These include press coverage of Brother Columba, some private letters to or from him, and a few published works about him. The vast majority of the collection—approximately 10,000 items—consists of letters to Brother Columba, either requesting his prayers or thanking him for some positive outcome attributed to those prayers. The bulk of the letters were sent between 1912 and 1924. O’Neill died in November 1923; letters arriving after are almost certainly from correspondents who had not yet learned of his passing.

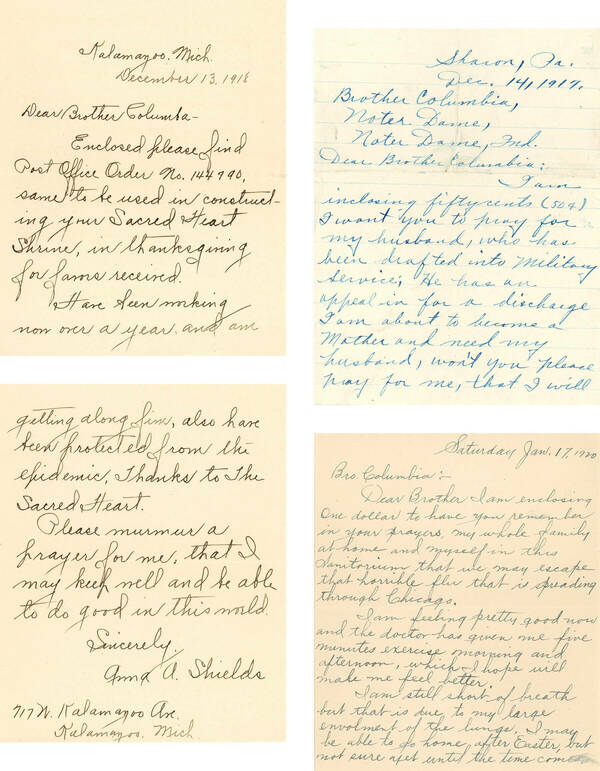

These letters give vivid color to a fuller picture of contemporary opinion on the war.

I do not know what to do dear Brother my two boys has to go to . . . to be exam for to go to the war Monday they have to put their clame in to be exem and dear Brother if thay have to go to the war I know i never can control my self so dear Brother wood you please say a prayer for them for I know nothing is imposbill with god for I always got help from holey prayers.11

Another correspondent asked for prayers for healing from influenza, as death would leave orphans behind:

Then the 2 of Dec I took influenza and that has left me very week. I am 49 just a bad age to fight diease. I am a widdow and have 2 Daughters at home that need my car, one 14 years 1 23 the one 23 is not very bright. I have a Son in Frace that would feel very bad if he had no Mother when he came home.12

Second, a remarkable aspect of letters to O’Neill is the balance they strike between major world events and correspondents’ individual needs—or, rather, a lack of balance. For example, a handful of letters like the above touch on the First World War and the 1918 influenza pandemic. But when correspondents do mention epochal current events, their letters almost always focus on what the correspondents need in their own lives. These letters give vivid color to a fuller picture of contemporary opinion on the war. Not uncommon were those requests for men to fail physical examinations or otherwise avoid war: “Pray that peace will be declared so that he will not have to go abroad and if he does have to go that God will watch over him and protect him”; “we hope he can get off but not much chance as he is not married”; “I am about to become a Mother and need my husband, won’t you please pray for me, that I will soon get him back.”13 Likewise letters mentioning the 1918 flu typically usually requested prayer for individual healing rather than a divine ending to the pandemic—even when acknowledging the affliction’s widespread nature. One correspondent sent O’Neill a dollar “to have you remember in your prayers, my whole family at home and myself in this Sanatorium that we may escape that horrible flu that is spreading through Chicago.”14

Third, how correspondents wrote to O’Neill also tells us a great deal about how contemporary Catholics understood theology. Many indicated a strong devotion to Jesus Christ in the form of the Sacred Heart. One woman wrote to O’Neill to ask for prayers for her friend: “She is a devout Catholic woman and I told her to never fear, the [Sacred Heart] had done so much for me, it would not fail her.”15 Another wrote to tell O’Neill she had been “working now over a year, and am getting along fine, also have been protected from epidemic, Thanks [sic] to the Sacred Heart.”16 Finally, another correspondent made an offhand comment exhibiting a robust understanding of the relationship between a concept like the Sacred Heart and the Catholic understanding of divinity: “of Course [sic] we all know the Sacred Heart is God Himself.”17

Yet others were not quite so clear—at least, not through their letters—on what the Catholic Church had long taught about intercessory prayer and who exactly the faithful should understand to be doing the healing. One Wisconsin woman reminded O’Neill that several years earlier, “through the Sacred Heart you cured me.”18 A Michigan correspondent reported on a prayer for “you to cure them if it was God’s Will [sic].”19 Finally, another clearly saw O’Neill as having special abilities himself, noting that “we are writing to you having heard of your visit to Kokomo [Indiana] and of your wonderful works among the Sick [sic].”20 Importantly, there is no evidence to suggest that Brother Columba ever took credit for anyone’s healing. His own devotion to the Sacred Heart was ironclad, and he never hesitated to attribute any positive outcome to the will of God. His advice was often of a piece with contemporary Catholic devotional culture—advising to say this or that prayer a certain number of times throughout the day, for example—but always indicated that prayer was to be directed to God to ask for God’s assistance.

Whoever O’Neill’s correspondents thought was responsible for healing or other positive outcomes, they believed that Brother Columba’s prayers improved their lives in ways both seemingly mundane and deeply significant—a cure for recurring but minor pain on the one hand, and avoidance of the horrors of frontline fighting in France, on the other. Few of those who sought his help did so with lofty goals in mind, like an end to World War I and a return to world peace. Most who wrote to O’Neill hoped his holiness would bring some relief to difficult situations in which they found themselves as individuals. In that sense, the thousands of letters to Brother Columba attest to the deep piety and personal faith of American Catholics in the early 20th century. Even in the face of global cataclysms like the war and the influenza pandemic that followed it, these men and women did not believe God was too busy to attend to their own problems—no matter how small they may sound to those reading the seemingly endless volumes of letters to O’Neill.

Patient petition

O’Neill’s intense holiness, cultivated over decades of prayers to God to help those who had written to him, was almost forgotten in the years after his death. But his memory has been revived. Brother Columba O’Neill formally gained the title “Servant of God” when his cause for canonization was opened in 2022 by Kevin Rhoades, bishop of the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend, at the request of the Brothers of Holy Cross.21 O’Neill’s cause underwent investigation by the five Catholic bishops in Indiana and received approval to be submitted to the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints at the Vatican.22 The process is no less bureaucratic than it sounds, and it is likely that O’Neill’s cause will remain at the “Servant of God” stage for some time to come—if it changes at all. A protracted period of little movement in O’Neill’s cause would hardly be anomalous in the history of the Church’s saint-recognizing process: while the Vatican began declaring men and women to be saints at breakneck speed starting with Pope John Paul II—including, eventually, that pope himself—prior to the 20th century, canonization was a fairly rare and extraordinarily long process. For someone like O’Neill, who played a powerful role in the lives of many people but remained largely unknown outside that circle of correspondence, a lengthy path to canonization perhaps should be expected. Believers, of course, suspect that O’Neill won’t mind.

Michael Skaggs is a historian of American Catholicism living in South Bend, Indiana. He is a visiting research scholar in the Department of Sociology at Brandeis University and director of programs for the Chaplaincy Innovation Lab.

This essay appears in the fall 2023 issue of the Cushwa Center’s American Catholic Studies Newsletter.

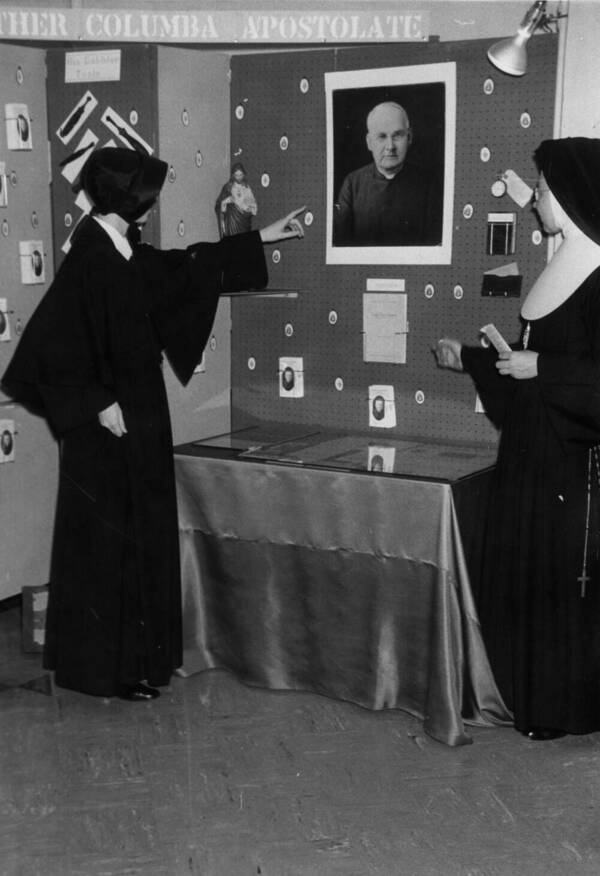

The Congregation of Holy Cross and the University of Notre Dame are remembering Brother Columba in several ways as the centenary of his death approaches (November 20, 2023). “Path to Sainthood: Brother Columba O’Neill,” a spotlight exhibit at Rare Books and Special Collections (102 Hesburgh Library), is available for viewing through October and November.

1 Edwin Donnelly and Philip R. Smith, C.S.C., “Servant of God, Brother Columba (John) O’Neill, CSC,” 4, https://brothercolumba.com/wp-content/uploads/Columba-bio-Rome.pdf, accessed May 15, 2023.

2 Donnelly and Smith, “Servant of God,” 5.

3 Charles L. O’Connell, C.S.C., funeral oration for Brother Columba O’Neill, quoted in “Circular Letter of the Reverend Provincial,” November 22, 1923.

4 For an overview of this process, see Kenneth Woodward, Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Becomes A Saint, Who Doesn’t, and Why (New York: Touchstone, 1996). The historiography of American saints has grown enormously in recent years, with landmark contributions in Emma Anderson’s The Death and Afterlife of the North American Martyrs (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013); Kathleen Sprows Cummings’ A Saint of Our Own: How the Quest for a Holy Hero Helped Catholics Become American (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019); Celia Cussen’s Black Saint of the Americas: The Life and Afterlife of Martín de Porres (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014); Allan Greer’s Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); and Catherine O’Donnell’s Elizabeth Ann Seton: A Life (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018).

5 Cummings, A Saint of Our Own, 5.

6 Leo Berner, “Shrine of the Sacred Heart at University of Notre Dame Most Beautiful in the Country,” South Bend Tribune, April 15, 1916, 7.

7 “Brother Columba Dies; Known as Miracle Man,” South Bend Tribune, November 20, 1923, 1 and 2.

8 “‘Notre Dame’s Miracle Man,’ Cobbler, Born 86 Years Ago,” South Bend Tribune, November 4, 1934, 8.

9 Donnelly and Smith, “Servant of God,” 4. Kevin McNamara, then archbishop of Dublin, summarized the traditional Catholic devotion to the “hearts” of Jesus of Nazareth and his mother in 1985: “Both the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary are symbols . . . Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus is devotion to Our Lord and Saviour who loves us with an infinite love and who showed that love for us above all by dying on the Cross for our salvation. Devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary is devotion to her on whom God has poured out his love in abundance and who now shares that love with us and never ceases in her efforts to establish it in our souls.” Kevin McNamara, “Devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary,” The Furrow 36:10 (1985), 600.

10 Donnelly and Smith, “Servant of God,” 5.

11 Mrs. James Tyson to Columba O’Neill, August 17, 1917, Archives of the Brothers of Holy Cross (ABHC) Midwest Province.

12 Louise Haft to Columba O’Neill, January 2, 1919, ABHC Midwest Province.

13 Dorothy K. Blackman to Columba O’Neill, August 21, 1917; Mrs. William Cheevers to Columba O’Neill, August 24, 1917; Mrs. Earl Woodford to Columba O’Neill, December 14, 1917, ABHC Midwest Province.

14 Mrs. D. Sullivan to Columba O’Neill, January 17, 1920, ABHC Midwest Province.

15 Mrs. Jas. L. Murray to Columba O’Neill, June 1, 1919, ABHC Midwest Province.

16 Anna A. Shields to Columba O’Neill, December 13, 1918, ABHC Midwest Province.

17 Paul J. McCarthy to Columba O’Neill, August 6, 1921, ABHC Midwest Province.

18 Marie Sage to Columba O’Neill, October 18, 1919, ABHC Midwest Province. Emphasis added.

19 Helen Dittman to Columba O’Neill, October 8, 1920, ABHC Midwest Province. Emphasis added.

20 JB Graves to Columba O’Neill, October 11, 1921, ABHC Midwest Province. Emphasis added.

21 Michael R. Heinlein, “An American André?” Our Sunday Visitor, September 15, 2022, https://www.oursundayvisitor.com/an-american-andre/, accessed May 11, 2023.

22 Christopher Lushis, “Pursuit of Cause for Beatification for Holy Cross Brother Columba O’Neill Continues,” Today’s Catholic, June 12, 2023, https://todayscatholic.org/pursuit-of-cause-for-beatification-for-holy-cross-brother-columba-oneill-continues/, accessed June 14, 2023.