Gabriela Perez

Gabriela Perez

Gabriela Perez recently completed her M.T.S. at Harvard Divinity School and is currently at work on a project titled “Patricio Flores: An Intellectual History of a Chicano Priest.” She received a 2018 Research Travel Grant to study relevant sources on Archbishop Flores (1929–2017) in the PADRES collection at the University of Notre Dame Archives. Cushwa Center postdoctoral fellow Peter Cajka met with Perez during her recent visit to discuss her project.

PC: Tell us about Patricio Fernandez Flores. Why is he a significant figure in American Catholic history?

GP: In 1970, Patrick Flores became the first Mexican American bishop in the United States. While making up a significant portion of the Catholic population, Mexican Americans in the Southwest continued to practice Catholicism without holding positions of authority. Flores’ role as bishop, and later archbishop, became more than a moment of celebration or an opportunity to voice the concerns of Mexican American Catholics; it was a moment of hope that the Catholic Church in the United States could do more for its laity. For Flores, this was a moment where the Catholic Church in the United States could be on the side of the oppressed, or Mexican Americans.

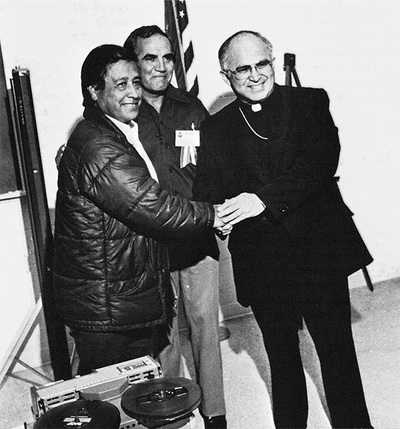

César Chávez, Father Roberto Peña, and Archbishop Flores

César Chávez, Father Roberto Peña, and Archbishop Flores

PC: How do the Notre Dame Archives help to illuminate Flores’ thought?

GP: The archives house the PADRES collection and this is what I’ve focused on during my visit. Although the PADRES collection only consists of the records kept by Father Juan Romero and Father Ramon Gaitan, its contents have been useful in reading against the grain to recover Flores’ voice.

Flores was a PADRES member before he became national chairman of the organization in 1972. While he wasn’t the center of the PADRES movement, he frequently served as a keynote speaker at many PADRES events. His involvement with PADRES, then, became a manifestation of the strand of liberation theology that influenced him. This strand of liberation ends up being a foundation for his pastoral priorities within the American Catholic Church.

PC: How will these archival sources help you to write an intellectual history of Chicano theology?

GP: I think these sources indicate how Chicanos, particularly Catholic Chicano priests, were aware of the systems around them. PADRES came about because the Chicano priests could not see themselves in the Catholic Church during the 1960s, or even decades before that. PADRES, and to some extent Flores, did not want to assimilate entirely into an American Catholic Church that demanded an erasure of their language and culture. With this in mind, the Chicano movement as well as liberation theology in Latin America offered these Chicano priests, and Flores, the ability to situate themselves within a politicized and historical moment. They recognized their colonial legacy and aimed not just simply to exist within the Catholic Church but to find ways of liberating others through the Catholic Church. This intentionality provides a good starting point for an intellectual history of Chicano theology.

PC: How will recovering this story shape the broader narratives of American Catholic history?

GP: Recovering this narrative, and particularly that of Flores’ life, helps to answer questions about identity within the Catholic Church in the United States. To what extent is the Catholic Church used to assimilate communities within a larger American society? What happens when communities choose not to assimilate? Is unity in the Catholic Church possible amid so much diversity? How do notions of liberation theology interact with a largely, historically European American Catholicism? Is it even possible to incorporate Mexican American Catholics into a larger American Catholic history? What would that look like?

PC: How did place—specifically Texas and San Antonio—shape Flores’ Catholic thought?

GP: I cannot fully answer this question based on the sources in the PADRES Collection. However, other sources indicate that racial segregation within the Catholic Church during the 1930s influenced Flores’ notions of what the Catholic Church in Texas could, and should, do to bring about justice. For instance, in June 1972, in an address to the First National Hispano Pastoral Encounter at Trinity College, Washington, D.C., Flores says:

Not too long ago, it was common for churches to have signs saying “Mexicans not allowed” or “The last four benches reserved for Mexicans.” … In some parishes, even though the physical doors have been opened, the North American people have not opened the doors of their hearts.

In my many visits to the Spanish-speaking, how often the migrants tell me that the churches do not want to allow them masses in Spanish, nor the use of parish halls for meetings, or if they do loan the hall, someone comes to fumigate it even before the meeting is over in order to deodorize it of the Mexican and Puerto Rican odor.

Two weeks ago a pastor asked my friend Encarnación Armas why Puerto Rican and Mexican Americans didn’t take baths more often so that they could change their color and then there would be no problem in accepting them in the American parishes.[1]

Flores lived and worked in Texas most of his life. Even if the particular incidents he mentions here did not all take place within Texas, they did happen within the Catholic Church, and they galvanized a sense of being separate and unequal within the Church. Flores, alongside other Chicano priests, would later speak out about this inequality.

PC: Tell us about your favorite source found in the Notre Dame Archives.

GP: My favorite source from the archives is a PADRES newsletter from February 1973 that describes Flores’ invitation to Dom Helder Camara to attend a PADRES national retreat. Here, the phrase “in conversation with” comes to mind as these two bishops—one from North America and the other from South America, both influenced by liberation theology—come together in Tucson, Arizona, to talk about Chicano ministry in the face of injustice (the theme of the retreat). I find this meeting of great minds fascinating.

PC: What are the next steps for this project? Having just completed the M.T.S. at Harvard, what's next for you?

GP: I'll be presenting this work under the Roman Catholic Studies Unit (Theme: Migration, Immigration, and Diversity in the Catholic Church) at the American Academy of Religion conference in November. After that, I'll submit the paper for publication. Later this year, I'll be applying to Ph.D. programs, as the goal is to continue doing research on historically marginalized voices.

[1] Bishop Patricio Flores, “The Church: Diocesan and National,” in Prophets Denied Honor: An Anthology on the Hispano Church of the United States, (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1980), 191.