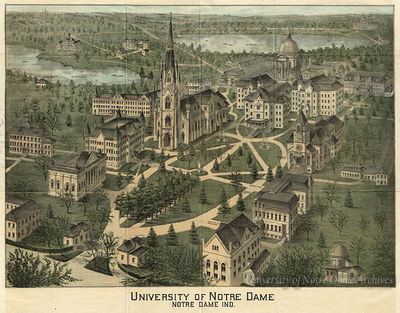

from the University of Notre Dame Archives.

The coronavirus has made life difficult for historians who might eventually have a chance to do research in the Archives of the University of Notre Dame. The online resources of the archives, however, allow researchers to make some progress in spite of the pandemic.

Imagine scholars reading The University of Notre Dame: A History (Notre Dame Press, 2020) by Rev. Thomas E. Blantz, C.S.C. They must have some interest in Notre Dame, but they relate what they read to their own research. When they teach they may emphasize the importance of primary sources, and yet acknowledge that secondary sources come first, that original research owes much to numbered notes ignored by the general reader, notes pointing the way for adventurous investigators.

Father Blantz has written a book engaging enough for the general reader, a book that also provides many promising clues for scholarly detectives—and not only for those who want to write about Notre Dame. Notre Dame’s modest role in American history means that even scholars who have no intention of writing about the University may, as they read its story, find their way to primary sources of interest. Those who do aspire to write the next book or article about Notre Dame can follow the footnotes to the University Archives. Those who have no such aspiration may find themselves there as well.

Father Blantz served as the university archivist in the 1970s. Later, as a professor in Notre Dame’s history department, he spent hours in the archives doing research. The Notre Dame Archives supports research into the history of the University by way of its website, with links allowing researchers to explore some holdings without having to come to the University in person. When scholars find something of interest, they can often order scans or photocopies or examine documents in a digital reading room. They can also see the full text of many documents on the digital collections webpage. Here they will find circular letters and correspondence of Father Edward Sorin, first president of Notre Dame, correspondence of Father Julius A. Nieuwland, inventor of synthetic rubber, and speeches of Father Theodore M. Hesburgh.

The digital collections page also has links to Notre Dame publications, including commencement programs, annual catalogs, an 1865 Guide to Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s, jubilee histories of Notre Dame, the Notre Dame Football Review, the Bagby glass plate sports photographs, the Religious Bulletin, directories, alumni magazines, schedules of courses, press releases, the president’s newsletter, and Notre Dame Report. But for Notre Dame history, the most important digital collections provide insights into campus life over long periods of time. Starting in 1867, the Notre Dame Scholastic, a weekly magazine with room for faculty and students in its pages, published articles about campus concerns and about Catholic concerns in the world beyond the campus. Since 1966, the Observer has served as the daily student newspaper for the University.

Another resource for Notre Dame history, from an earlier version of the archives’ website, tells “The Story of Notre Dame” through selected holdings of the archives: the centennial history of the University, Notre Dame—100 Years by Arthur J. Hope, C.S.C.; The Chronicles of Notre Dame du Lac by Edward Sorin, C.S.C.; The University of Notre Dame du Lac: Foundation, 1842–1857 by John Theodore Wack; Brother Aidan’s Extracts by Brother Aidan O’Reilly, C.S.C.; Academic Development: University of Notre Dame Past, Present and Future by Philip S. Moore, C.S.C.; My Fifty Years at Notre Dame by Leo R. Ward, C.S.C.; Twenty Septembers: A Memoir of Teaching by Elizabeth Christman; America–Europe: A Transatlantic Diary 1961–1989 by Klaus Lanzinger; Notre Dame Photo Gallery by Robert F. Ringel; Episodes in the Story of Notre Dame, A Documentary Exhibit; and The Legacy of Father Moreau, Founder of the Congregation of Holy Cross.

The Notre Dame Archives also maintains a page of links to specialized indexes based on records of students, faculty, and administrators, and on Notre Dame publications. This page includes a Notre Dame theatre chronology and a football program index.

In most cases, of course, scholars visiting the website will find descriptions of archival holdings rather than digital scans of documents. The latest tool for searching the archives, called ArchivesSpace, helps researchers find promising possibilities. For access to the documents, they have to communicate with the archives—these days nearly always by email or phone.

For those interested in Notre Dame history or in the history of the great world beyond the campus, some finding aids provide more information than others. Father Blantz tells the story of how Notre Dame came to collect Catholic historical records. When James Farnham Edwards started collecting Catholic manuscripts in the 19th century, he exchanged many letters with Catholics outside the campus. Father Daniel Hudson, during his long tenure as editor of the Ave Maria in the 19th century, also corresponded with Catholic writers from America and Europe. Father Paul Foik, early in the 20th century, began the project of providing detailed summaries of these and other letters to and from American Catholics, a project that continued through most of the 20th century and resulted in an archival calendar presently searchable on the archives website. The abstracts in the calendar follow the original documents closely, making this an especially useful resource.

The online edition of Records of the Diocese of Louisiana and the Floridas, 1576–1803, relies on calendar entries. The online edition of William Tecumseh Sherman Family Papers does not. But both illustrate a point Father Blantz makes about the history of the archives. Since the 19th century, Notre Dame has recognized the importance of preserving historical documents.

Many hours have gone into listing the letters in the early correspondence of Notre Dame presidents. One collection contains letters from several early presidents (1856–1906), and some later presidents have similar item lists. In the 19th century and early in the 20th century, most of the correspondence between Notre Dame and the outside world went through the president’s office. Individual presidents generated university records and (in separate collections) personal papers.

In the 21st century the archives received two collections especially significant for the history of Notre Dame. The general archives of the Congregation of Holy Cross and early U.S. province archives provide rich resources for research into the history of the University and of the religious congregation that founded and maintained it.

As Father Blantz explains, anyone interested in recent Notre Dame history has special challenges since the administrative records of the University remain closed for many years. But the distinction between personal papers and official records makes it possible for the archivists to provide access to some collections dating from these years. For example, Father Hesburgh’s digitized speeches and the finding aid for his other papers supplement the coverage of his years as president in campus publications.

Kevin Cawley retired in 2019 from his role as senior archivist and curator of manuscripts at the Archives of the University of Notre Dame, after 36 years of service.

This report appears in the spring 2021 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.