One in Christ:

Chicago Catholics and the Quest for Interracial Justice

Karen J. Johnson (Oxford University Press, 2018)

Review by Peter Cajka

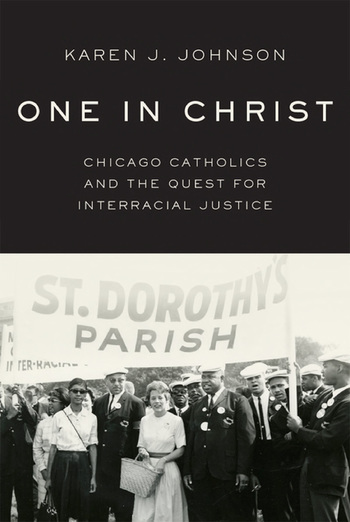

One of the iconic images of the Catholic 1960s comes out of Chicago, where crowds of white Catholics jeered at the sisters and priests who marched with Martin Luther King, Jr., in summer 1966. Arms linked, the band of consecrated men and women ducked their heads and braced their bodies, ready to take blows from members of their own Church. Angry, white Catholics demanded their clergy tend only to religion and stay out of politics.

That image both illuminates and obscures the history of civil rights as it relates to American Catholics. The civil rights movement did indeed divide the Church, but the sisters and priests in the march were hardly the first Chicago Catholics to fight for African Americans’ civil and economic rights. Karen Johnson’s deeply researched book, One in Christ: Chicago Catholics and the Quest for Interracial Justice, shows that “King joined an indigenous movement” (203), as the author phrases it. Johnson uncovers a network of Catholic individuals and institutions active in Chicago since 1930 for the purpose of fostering interracial justice. By the time King demonstrated on the streets of Chicago in the mid 1960s, highly committed Catholic activists had prepared segments of their city to receive his message.

Johnson focuses on an important coterie of Catholic activists who labored for interracial justice, examining the personal relationships among them and the tensions they created, especially with members of the hierarchy. Interracial justice, as they understood it, entailed tangible economic and material gains, along with the transformation of individual persons and of Chicago itself. Johnson’s approach is defined not by theological exegesis but by what she calls “the messiness of everyday life” (4). One in Christ offers the history of a theology put into action, with all the empowerment and contradictions that result.

The story begins with Dr. Arthur A. Falls’ rejection of the Church’s ethnic parish model and its missionary impulse to convert the African Americans who came to Chicago during the Great Migration. Falls, an African American doctor and a deeply committed Catholic, was active in many official ecclesial channels even as he chafed under the cautiously moderate programs of the Church. Johnson shows that the Catholic Action movement—in which white priests led black organizations—both helped and hindered the cause of interracial justice. Catholic Action’s mandate to take the Church into the world empowered these activists, but the priests set the agenda. While some of Chicago’s bishops paid lip service to interracial harmony, they preferred gradualist programs. Johnson finds that activists instead favored direct action meant to convert white Catholics to their cause. The book’s latter chapters shift to the national level to show how Chicago’s Catholic activists had an impact on federal civil rights legislation. Johnson also contends that Catholics in and beyond Chicago helped bring Protestants and Jews into the fold of the civil rights movement.

A real strength of One in Christ is the cast of characters the author introduces and develops. Johnson’s book moves the history of Catholicism and race relations well beyond John LaFarge, the Jesuit priest who commands much of the historiography. Crucial to Johnson’s intervention is her detailed analysis of Friendship House, a physical space where white and black Catholic Chicagoans could be transformed through social interaction. The organization’s philosophy, and the Friendship Houses themselves, were modeled on Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker communities. Chapter Four profiles Catherine de Hueck, a Canadian who began the Friendship House movement in Harlem and spread it across the north; Ellen Tarry, a dedicated apostle of Friendship House who admired the organizational prowess of American communists; and Ann Harrigan, a first-generation Irish Catholic who lectured frequently on interracial justice. Johnson makes a compelling case for the importance of these activists and the models they deployed at Friendship House: “In a small but personal way,” she writes, “FH, with its simple solution of interracial relationships—contextualized by concern for economic, legal, and religious discrimination—struck a blow at segregation’s stronghold” (98).

The theological world that Johnson describes is fascinating and revelatory. One in Christ offers an in-depth analysis of how Catholic Action worked in a specific arena, and Johnson demonstrates how Catholic theologies significantly influenced activists’ behavior. The book is impressive for its rich, multilayer analysis of religious experience. Readers traverse a finely-detailed religious landscape that was shaped and reshaped by the very human lives Johnson studies. Catholic activists truly believed themselves to be parts of the Mystical Body of Christ, and they imagined African Americans as “Christs” to be welcomed into community life. The Mystical Body holds that all individuals, Catholic or not, are different but essential parts of a larger organism. The notion of a Mystical Body helped activists conceive of Chicago as a broad spiritual ecosystem in which each part was essential to the health of the urban totality.

Johnson shows that this belief in a Mystical Body had two effects on the larger movement: first, the doctrine carved out a sizable sphere of activity for lay action, creating a unique division of labor between priests and lay activists. Whereas priests imagined Catholic Action as a means for the clergy and hierarchy to direct and even control the interracial movement, a combination of the Catholic Action paradigm and the Mystical Body doctrine allowed activists like Falls to see themselves as offering Christ to others by their physical actions in the world. Priests offered Christ on the altar during Mass; the laity offered Christ to those they encountered in the streets. Second, the Mystical Body made it impossible to be Catholic without caring for African Americans as Christ in their midst. Ellen Tarry captured the second dynamic well by telling the people of Friendship House to work with African Americans rather than working for them. The crucial task for the urban Church was to develop personal relations across the barriers of segregation that could then be used to challenge the prevailing economic, social, political, and legal system. They may have been a small group, but One in Christ demonstrates that these activists made interracial justice an important component of Catholic social teaching in the Chicago context after 1930.

To be sure, this theology and its promoters created tensions with Chicago’s bishops—and the movement encountered significant roadblocks in the form of concern over property values and the Church’s broadly gradualist tendencies. Yet, Johnson shows that the movement for interracial justice was vibrant, even awe-inspiring, in the breadth of its theological vision.

One in Christ makes a valuable addition to an already rich historiography on Chicago, race, and Catholicism. Johnson introduces a new group of historical subjects—lay Catholic interracial activists—into a field of vibrant characters. Historians have already made cases for the significance of Chicago’s missionary priests, Black Power activists, power-hungry Church officials, lay people in ethnic enclaves, neighborhood organizers, athletes, theologians, and black priests. Johnson moves the field much closer to a complete narrative. John McGreevy’s influential Parish Boundaries (1996) demonstrated how the overlap of faith and place helped to make ethnic Catholics particularly defensive about African Americans entering their neighborhoods. Timothy Neary’s Crossing Parish Boundaries (2016) complicated this picture by showing how youth sports provided opportunities for Catholics to transgress established boundaries for meaningful interactions with African Americans. Most recently, Matthew Cressler’s Authentically Black, Truly Catholic (2017) showed how the Black Power movement transformed Chicago’s African American Catholics, making the faith more explicitly political and leading to a great deal of liturgical experimentation. One of the interesting aspects of Cressler’s study is his focus on the missionary priests sent to black neighborhoods to win converts. To these accounts Johnson adds the programs launched by the Catholic Interracial Council and Friendship Houses. Johnson’s research offers the field new, suggestive evidence that white, Catholic activists played more than a marginal role in helping urban Catholicism confront the race question. Importantly, following historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s landmark argument for a “long civil rights movement,” Johnson shows convincingly that King’s 1966 march graced an intellectual and organizational infrastructure already built by lay Catholics decades prior.

The book’s guiding lens, “the messiness of everyday life,” is at once a useful and a somewhat limiting interpretive tool. The form of the book flows from the content of the complex lived existence narrated therein. At times, the reader could benefit from a wider perspective, which only arrives in the final chapters.

This book is an important contribution to several overlapping fields: Catholic history, urban history, the civil rights movement, and the history of Chicago. In light of Johnson’s findings, many new questions can be raised about Catholics, race, and urban life in the 20th century. The civil rights movement is far richer and theologically deeper than is usually understood. As Johnson notes in one of her study’s many wonderfully turned phrases, “Catholics’ public presence in the civil rights movement’s marches—in contrast to so much white intransigence on integration—was the tip of an iceberg of Catholic interracial activism” (225). In demonstrating this, One in Christ proves itself an important intervention that will have lasting effects on modern American history.

Peter Cajka is a postdoctoral research associate at the Cushwa Center.

This book review appears in the spring 2019 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.