When I was young, my grandparents told me about their civil rights work during the 1960s and 1970s. My grandmother, Rosemary Fairchild, worked with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, founders of the United Farm Workers of America. She spoke about scouring hours of video to find the phrase “There’s blood on those grapes,” which became a watchword for their demonstrations and speeches. My grandfather, Anthony Isidore, told me how he helped create the “Give a Damn” campaign for the New York Urban Coalition. It was an advertising campaign that used the rhetoric and imagery of segregation to demonstrate what it was like for many Black men and women attempting to gain access to housing and why others should care. Growing up with these stories while being raised Catholic, I often wondered why Catholic activists were not a part of the civil rights historical discourse. Their stories always made me think about the grassroots workers, specifically the women involved in the movement, and have guided me through my academic career.

As I began my master’s at the University of Alabama in 2019, I realized that the discourse surrounding religious participation in the civil rights movement was predominantly focused on Protestants, while the involvement of Catholic religious activists was rarely discussed. This became clearer as I mapped out major events of the movement for a research project. I came across a photo of nuns in habits—one Black sister and three white sisters—marching in Selma, Alabama, after “Bloody Sunday” in March 1965. I was shocked. I’d never seen this photo before and found myself asking, “Who were these religious women?” This led to bigger questions about the field, especially as I noticed that there had been little research into Black women religious.

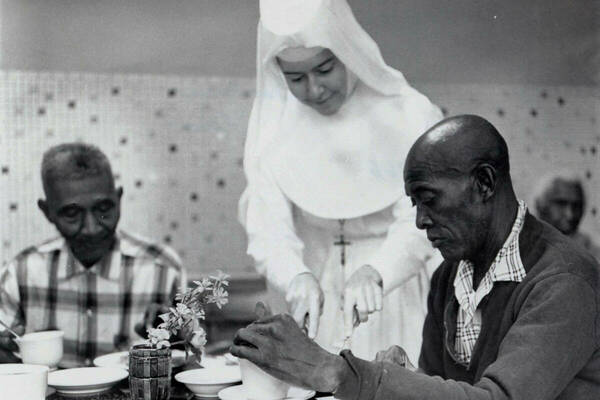

During my research of the four nuns in the photo (Sister Roberta Schmidt, C.S.J.; Sister Mary Antona Ebo, F.S.M., the only Black nun photographed; Sister Rosemary Flanigan, C.S.J.; and Sister Eugene Marie Smith, F.S.M.), I was lucky enough to interview three women who were in Selma at that time: Sister Rosemary, now a practicing philosopher; Sister Barbara Lum, S.S.J., a white sister who had been a nurse at the Edmundite Missions and treated civil rights activist John Lewis after the police attack; and Sister Barbara Moore, C.S.J., a Black nun who flew to Selma days after Bloody Sunday to participate in the subsequent marches. These women contextualized the march, its aftermath, and the Church’s response to demonstrations in states like Alabama, which had a very small Catholic population.

As I began to listen to the history of the women’s involvement in the civil rights movement, it became more apparent that while the institution of the American Catholic Church offered statements on racial justice and equality—such as the bishops’ statements on Discrimination and Christian Conscience (1958), the National Race Crisis (1968), and Brothers and Sisters to Us: Pastoral Letter on Racism (1979)—the Church continued to fall short on addressing discrimination within parishes and orders. Religious orders and Church hierarchy also restricted both men and women religious from participating in protests. According to Sister Barbara Lum, Archbishop Thomas Joseph Toolen forbade priests and nuns in the jurisdiction of Alabama from participating in civil rights demonstrations, ostensibly for the safety of the small Catholic population. When speaking about the sisters who flew to Selma from across the country, answering Martin Luther King’s call to join the voting rights marches, Toolen told the National Catholic Reporter, “Certainly, the sisters are out of place in these demonstrations. Their place is at home doing God’s work.” While the quote highlights a perspective that some in the Church hierarchy held, the sisters would have thought of their involvement differently. One could argue that these women were doing God’s work by demonstrating in Selma, participating in a kneel-in in front of the Dallas County Courthouse, or marching 51 miles with activists to Montgomery over five days.

While there has been scholarship on Black Catholic history, such as the pioneering scholar Father Cyprian Davis, O.S.B.’s books The History of Black Catholics in the United States (1995) and Taking Down Our Harps: Black Catholics in the United States (1998), such work has addressed African American religious life in the Catholic Church broadly but without enough attention to Black women religious. Scholarship on Black women religious has only recently entered the discourse with Shannen Dee Williams’ publication of Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle (see the interview with Williams for the fall 2022 American Catholic Studies Newsletter here). While Williams’ book is a much-needed start, the history of Black women religious still needs further examination.

Though my project is very much in its early stages, it is evident that the history of women religious needs to be integrated into the story of the civil rights movement, especially the involvement of Black women religious. While women religious were being told to stay out of public demonstrations, they were fighting for racial equality within their orders. This included Sister Barbara Moore, C.S.J., who in 1955 was the first African American woman to desegregate her order. These women were breaking down racial barriers and desegregating what had previously been white-only space, working in communities that had previously been sundown towns, and offering safe havens for civil rights workers to meet when local governments banned such gatherings in public spaces. When we examine the histories of Black and white sisters who assisted in desegregating parishes, orders, and parochial schools, we see an untold history of Catholic activists and the civil rights movement.

I study women religious because their histories and contributions matter despite being previously ignored. These women have helped change the makeup of the Catholic Church and the country, yet their accounts have been overlooked or, in some cases, erased, making them incredibly difficult to learn about, never mind write about. Too few people have heard of these women and their impact on the United States. As a religious studies scholar, I research these women so their histories are not forgotten and so those in the fields of religious studies, history, and Catholic studies—as well as the general public—can learn about them.

Allison Isidore is a doctoral student in religious studies at the University of Iowa. She also serves as assistant director for the American Catholic Historical Association (ACHA) and as one of the hosts of the ACHA’s podcast “New Books in Catholic Studies.”

Image: Sister Barbara Lum, S.S.J., with residents at Good Samaritan Hospital Nursing Home, 1966. Original photo by Sister Mary John Van Atta, S.S.J. Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Rochester, New York.

This piece appears in the fall 2022 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.

Editor's note: At the author's request, the second-to-last paragraph of this guest column has been updated on this webpage. In the print/PDF version of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter, the paragraph appears as it was originally published (pp. 30–2).