Why I Study Women Religious

By Thomas Rzeznik

Associate Professor of History, Seton Hall University

Rzeznik

Rzeznik

I hadn’t planned to study nuns. Sure, I could claim a long-standing fascination with them. I had sisters as teachers in both elementary school and high school, most of whom still wore habits. I am perhaps in the minority among my generation still to have had that experience. The names of those who taught me in the earliest grades—Presentata, Valencia, Aselle—both taxed my spelling skills and added to my teachers’ intrigue. But that air of mystery surrounding the sisters never translated into an abiding intellectual curiosity about them. In graduate school, though interested in the place of Catholicism within American religious life, I turned my attention to Gilded Age affairs. In particular, I found myself drawn to the lives of the financial elite. I wanted to know more about their religious worldviews and the influence they had on their local churches and broader denominations through their philanthropy. My research strategy of “following the money” wasn’t likely to lead me to the convent door.

Or so I thought. My decision to focus my research on Philadelphia brought the pleasure of several visits to the Motherhouse of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, the religious order founded by Katharine Drexel, one of the wealthiest women of her day. She used her inheritance of a banking fortune to support missionary outreach to blacks and Native Americans, sponsoring churches and schools throughout the American South and West and sustaining the work of her religious community.

But did studying Katharine Drexel really count as “studying women religious“? She was hardly representative of the vast majority of sisters. Even though she felt a deep vocation, lived a devout life, and held herself to the same standards of poverty she expected of all members of her religious community, she was, through it all, a “millionaire nun.” Since the nature of her trust fund made it impossible for her to transfer legal control of her wealth to her religious order, she continued to control her own assets even after she entered the convent. As a result, she was distinguished not only by her wealth, but by the autonomy it afforded her. She retained her personal identity, set her own philanthropic agenda, executed and scrutinized contracts, and conducted her business affairs with an acumen that rivaled her economic equals.

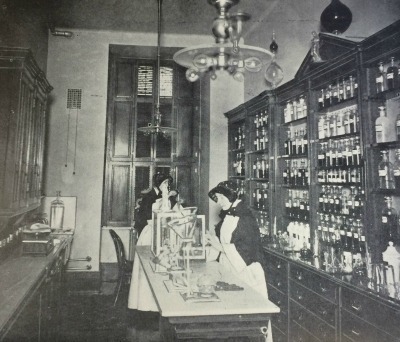

Sisters of Charity preparing medicines in the pharmacy of St. Vincent's Hospital, New York City, c. 1900. Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of New York.

Sisters of Charity preparing medicines in the pharmacy of St. Vincent's Hospital, New York City, c. 1900. Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of New York.

Although Drexel may have been exceptional, I’ve come to realize that she was not as atypical as she might at first appear. Studying her life and career made me more mindful of the corporate activities of women religious and their role in building, sustaining, and managing the institutional life of the church. Drexel and her community were responsible for expanding the church’s physical presence and serving those at its social and geographic peripheries. In the process, they advanced a new vision of what the church might be.

I’ve come to appreciate how women religious did more than simply staff Catholic institutions. Rather, they supplied those institutions with their animating spirit and inner dynamism. That insight has become all the more apparent to me in my current work on the history of St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York City. Founded by the Sisters of Charity in 1848, it stood at the vanguard of Catholic healthcare for more than 150 years. It’s especially noteworthy for its commitment to providing care for the poor and marginalized, from immigrants and orphans to the early patients of the AIDS crisis. It was the physical manifestation of the order’s mission and charism.

I hope that my work on St. Vincent’s helps draw attention not just to the work of women religious as nurses and caregivers, but to their ability to carve out space and create structures that enabled them to live their vocations and advance the Church’s social mission. I’m also interested in what studying the life cycle of an institution like St. Vincent’s can tell us about the trajectory of its sponsoring religious community. The Sisters of Charity were involved so intimately in so many aspects of the hospital’s development and operations that their identity became virtually inseparable from the hospital’s. More reflection is needed on what the institutions they established meant for women religious, not only as those institutions developed and grew, but also as they declined or took on new life. As all those who study women religious know, there is much research still waiting to be done!

This column appeared in the History of Women Religious section of the Spring 2016 American Catholic Studies Newsletter.