History of Women Religious | Lead Story

Remembering Mother Cabrini: Constructing the Saint’s Memory and the Sacred in New Orleans, New York, and Rome

by Katie Berchak-Irby

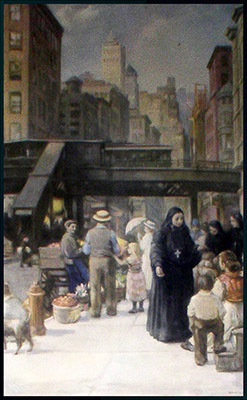

"Saint Among the Skyscrapers," by Robert Smith.*

"Saint Among the Skyscrapers," by Robert Smith.*

St. Frances Xavier Cabrini (1850–1917) is the Patroness of Immigrants, founder of the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and the first American citizen to be canonized. She is also one of two saints whose “body figure” relics are on display in the United States. Today, her order operates in more than 15 countries around the globe, with most of its focus on girls’ education, services for immigrants, and healthcare. I graduated from the order’s Cabrini High School in New Orleans, where we were taught how special it was to walk on ground on a campus where a saint once lived and worked. “Mother Cabrini,” as we called her—never the impersonal “St. Cabrini”—lived in a building that was once an orphanage. Though the school uses the building today for classrooms and administrative space, her bedroom is still maintained as if she will return at any time.

It was years ago as a student at Cabrini High that my interest in women, saints, shrines, and memory began. I was fascinated by the stories women in the extended Cabrini community told about the school, the bedroom, and the women and girls they befriended because of Cabrini. On vacations to New York City as a young adult, I developed a similar interest in the St. Frances Xavier Cabrini Shrine in Washington Heights, where Mother Cabrini’s “body” laid atop the chapel’s altar in a glass and gold casket like Snow White. Eventually, these two sites became the field sites for my dissertation in the Department of Geography and Anthropology at Louisiana State University.

Geographers haven’t been as keen to study religion as other social scientists. Those who do mostly examine cemeteries, memorial landscapes, and contested sacred places and few geographers of religion have used ethnographic methods at these sites. The living people at these sacred spaces were often ignored in the Catholic Studies and geography literature, with a few notable exceptions like the work of Robert Orsi and Thomas Tweed. So I set out to talk to the people—most of them women—at and connected to my two field sites and to investigate what made these sites sacred to them.

Memories and Family

Mother Cabrini's preserved bedroom at Cabrini High School, New Orleans (photo: author)

Mother Cabrini's preserved bedroom at Cabrini High School, New Orleans (photo: author)

The high school in New Orleans uses Cabrini’s bedroom as a recruitment tool. In a city in which a large percentage of high school students enroll in one of the area’s Catholic high schools, schools host open house tours and market themselves to a large pool of potential students. Cabrini High can claim an important distinction: their students walk on holy ground. During open house tours, students and their parents are taken to Mother Cabrini’s bedroom, where they are greeted by a student dressed as Mother Cabrini. Interviewing alumnae, faculty, and staff, I found that what made Cabrini High and the bedroom special for them had less to do with the details of Mother Cabrini’s own biography and more to do with the memories they had at the school or with women they’d met because of the school.

Many of the older alumnae related the bedroom to their own fond memories of a time when more sisters worked and taught at the school. One alumna said that the school’s founding principal required all of the girls to come to the convent before their off-campus prom, ostensibly so that she could check to make sure their dresses met modesty standards, when in reality, she wanted to see the girls and their dates, just like many parents make their teens pose for pre-prom pictures in formal wear. The sisters, the lay faculty, and the students became a family. Visiting Mother Cabrini’s room now is a way to engage with those memories of this Cabrini “family,” many members of which are now deceased. I also found similar accounts as recently as my graduating class (2001); my classmates said that visiting campus was a way to engage with the past and now-deceased family, as well as a classmate who was killed by a drunk driver in 2005.

At the New York City shrine, I found similar responses. While many of the women who visited the shrine were Hispanic immigrants, they also reported going to the shrine not just because of Mother Cabrini’s status as Patroness of Immigrants, but also because going there reminded them of now-deceased family or friends with whom they had once visited the shrine, or of family back home, or because the shrine reminded them of churches in their homelands.

Shrines and Bodies

Cabrini's body figure in New York (photo: author)

Cabrini's body figure in New York (photo: author)

When I first visited Cabrini’s New York shrine as a teenager, I thought that the figure in the glass coffin was in fact the saint’s incorruptible, or undecayed, body. I’d been told by the sisters in New Orleans as a high school student that “Mother Cabrini’s body is in New York.” A few years after graduation, however, a sister told me it was a “body figure”—Cabrini’s torso encased in a wax replica of her body. For four years of high school, without even giving it much thought, I studied feet away from a bedroom that was waiting for the return of a dead saint. It was a little bizarre that I was now standing in front of a body that wasn’t a body after all. I didn’t know then that this was just the beginning of the surprises I’d encounter as I pressed forward with my fieldwork.

I began to research body figures. It will come to no surprise to readers of this newsletter that body figures of saints are very common in Catholicism and quite prolific in Europe (particularly in Italy and France). While other types of relics are common in the United States, body figures here are limited only to Mother Cabrini’s and Saint John Neumann’s in Philadelphia. Body figures are not a large part of American Catholicism and Catholic culture that was largely influenced by the Irish; body figures are not common in Ireland’s Catholic churches and shrines. Mother Cabrini’s body was found to have decomposed in the normal manner when it was exhumed in 1933 from her resting place on the order’s property in West Park, New York, as part of her canonization process. Her body, like those of would-be-saints before and after her, was then taken apart and parceled out to the order’s missions, schools, hospitals, and other institutions. The New Orleans orphanage that would become Cabrini High ended up with bone fragments; the order’s hospital in Chicago got a whole tibia. On the property where the Cabrini shrine stands in New York, the order operated an all-girls high school until 2014, when the school—which in later years served mostly Hispanic, low-income students from the local area— was no longer fiscally viable. The shrine is still open and operating on the property. In 1933, Mother Cabrini’s body figure arrived at the school from Rome, where the Vatican’s mortuary team had removed some parts of the body for relics and encased the remaining torso in a realistic wax effigy. It was initially housed in the school’s chapel. In 1957, a new, modern, amphitheater-style chapel was built adjacent to the school and the body figure was relocated to its altar.

Discovering the story of Cabrini’s body in the United States wasn’t the end of my journey, however. While interviewing a sister who was visiting Cabrini High in New Orleans and looking around the bedroom with her, I asked her if a picture on the wall of Mother Cabrini’s body in a traditional-looking chapel was the original chapel at the New York school. She replied matter-of-factly, “No. That’s the other body in Rome,” and quickly changed the subject. I pushed the thought to the back of my mind. The other body? I had graduated from this high school, had interviewed countless sisters, spent summers doing field work at the New York shrine that houses what I assumed to be her only “body” and now was being told that there’s another body? After investigating further—using my limited Italian—I pinpointed the “other body” at the order’s retired sisters’ home in Rome and, having made email contact with a sister there, set out to see it.

Mother Cabrini's body figure in Rome (photo: author)

Mother Cabrini's body figure in Rome (photo: author)

I knew that due to time and monetary constraints, I would not be able to do field work there as in-depth as I had done at my other two sites. The secrecy surrounding the second body also made it clear to me that no long-term fieldwork would be possible in Rome. I was content to be allowed into the chapel at the retired sisters’ home to see what I found to be not a “secret” body so much as a “private” one for the now-elderly women who had committed their lives to Mother Cabrini’s mission. An Italian sister, who had worked in New Orleans decades before, greeted me warmly. She took me into the chapel, where she left me alone with the body. This “body,” it turned out, is also really a body figure, but it looked slightly different from its New York twin. In Rome, Mother Cabrini’s face is tilted slightly to the side so as to look at its visitors, whereas the New York body’s head faces the ceiling. The face in Rome is also softer; Mother Cabrini has a slight smile compared to her stone-faced counterpart in New York. Here was the sisters’ private Mother Cabrini—smiling, at ease, and truly at home with her community.

Intercessions: From Thanks to Death

In the bedroom in New Orleans, students and other visitors may leave special intentions for Mother Cabrini’s intercession in a small box on slips of paper provided by the school. At the New York shrine, many people leave ex-votos, such as letters, engraved plaques, and pictures, in thanks for requests granted. The sisters keep many of them in museum-like wings off the sides of the shrines. Some have to do with citizenship and immigration or health issues, but many offer thanks, mostly from women, for degrees and educational programs completed. Anthropologist Miles Richardson wrote that ex-votos are a way of leaving presence in our absence. When we leave the shrines, we leave pieces of ourselves behind in ex-votos.

Like many ethnographers before me, I was to discover that pieces of myself were unexpectedly engaged at my research site. In 2012, I was teaching full-time at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. One of our students, anthropology undergraduate Michaela “Mickey” Shunick, was abducted and murdered as she bicycled home near the campus bike trail, an area where I often ran after work. An arrest had been made when I left to do my summer field work at the shrine in New York. Although law enforcement believed she had been murdered and a convicted sex-offender named Brandon Lavergne had been arrested, her body’s location was unknown. As a reader of true crime and the daughter of a retired military law enforcement officer, I knew the case against her alleged murderer would be stronger with her remains. Although not a particularly devout Catholic myself, I figured it couldn’t hurt to ask for Mother Cabrini’s help. I kept up with the news from Louisiana; days and weeks went by without the discovery of Shunick’s remains. One morning I was fed-up that there had been no developments. I walked up to the coffin and got down next to it. I didn’t ask in a quiet whisper for Mother Cabrini’s help as I had done before. (Mother Cabrini, from all accounts, wasn’t one to ask politely. When she needed more money than a wealthy Italian sea captain was willing to donate to build an orphanage in New Orleans, she told him that it was not enough and that she would need more. He complied.) “She needs to be found,” I demanded. Later that evening while I ate dinner, my mother called from Louisiana to say Mickey’s body had been found. In that moment, I believed in miracles—or at least in this one. I got chills and goosebumps. Later, I’d learn that the same morning I was imploring Mother Cabrini for help, Mickey’s killer had been working out a plea deal where he led police to her body in exchange for the death penalty being taken off the table. Perhaps my miracle was nothing more than a narcissistic, sociopath killer saving his own life. But it almost didn’t matter—in that moment, it had been real. It also allowed—or perhaps forced—me to confront death at the shrines. In coding my field notes and interview transcriptions, I found that death kept coming up; it could not be ignored.

Women use all three of the Cabrini shrines—in New Orleans, New York, and Rome—to engage with the past, with dead loved ones, with dead members of the community, and to make meaning of death—and therefore, life. My research started out primarily ethnographic but ended up becoming autoethnographic as well. After I told my advisors and my graduate cohort what had happened at the New York shrine at the time of the finding of Mickey’s body, they encouraged me to include my own story about death in my dissertation. When I returned to Louisiana, I had a plaque made thanking Mother Cabrini for her help in finding Mickey’s body. By then I felt removed from how real that “miracle” felt, and knew that her killer had given up the location of the body. But that didn’t matter. I was sending something to be left in New York that would become a part—my part—of making the sacred and memory at the shrine.

I had set out to study the women who used the shrines to negotiate death and the past, and now I was one of them. Like many other women, at the shrines I found gendered spaces—operated and owned by women and mostly visited by women—within the larger male-dominated hierarchy of the Catholic Church. There, women have been able, with a rich material culture, to construct the sacred around memories, the past, members of the Cabrinian community, death, and life.

Berchak-Irby with a bust of Cabrini outside her New York shrine

Berchak-Irby with a bust of Cabrini outside her New York shrine

Katie Berchak-Irby holds her Ph.D. from Louisiana State University in geography and anthropology. She is an instructor of geography, anthropology, and Spanish at River Parishes Community College in Gonzales, Louisiana.

*Image Courtesy of Cabrini College Archives