Bronagh McShane, Ph.D., is a former postdoctoral fellow in the humanities at the Moore Institute at the National University of Ireland, Galway. She earned her doctorate in history from the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, and specializes in the history of women, religion, and confessionalization. Last year, the Cushwa Center awarded McShane a Mother Theodore Guerin Research Travel Grant for her project “Irish Women Religious, c. 1530–1756: Suppression, Migration and Reintegration.” We caught up recently to discuss her work.

Shane Ulbrich: Your latest project isn’t the first time your work has dealt with women religious. They’re central to your dissertation as well as a number of articles you’ve published in the past few years. Tell us about some of your previous research.

Bronagh McShane: My interest in the history of women religious began during my doctoral studies at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth. My thesis examined the impact of the Reformation on women in Ireland from the Elizabethan era down to the mid-17th century. One of the key groups impacted by religious reforms during this period were women religious; the official closure of the monasteries in Ireland in the 1530s and 1540s had serious repercussions for women wishing to adhere to a religious lifestyle. In the decades after 1540, migration abroad became one of the only viable options for this cohort. The same was true of their English counterparts. My interest in the experiences of Irish nuns both in Ireland and abroad formed the basis of my current book project.

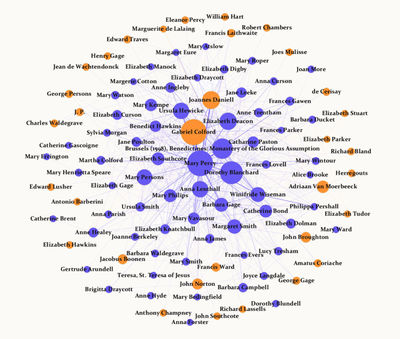

Research on women religious was also central to my work as a postdoctoral researcher on the European Research Council-funded project The Reception and Circulation of Early Modern Women’s Writing, 1550–1700." As a researcher on this project, I analyzed scores of letters penned by a community of English Benedictine nuns based in Brussels during the 17th century. The English Benedictine convent in Brussels was the first convent for English women to be established on the Continent after the Reformation. Based on that research, my article, published in the Journal of Historical Network Research (2018), pioneered the application of network analysis tools to letters written by and about early modern women religious.

SU: What is network analysis and how does it help us better understand early modern nuns?

out-degree.

BM: A network is a set of relationships between objects or individuals. Objects or individuals are normally referred to as “nodes” in the network and their relationships as “edges” (Ahnert, 2016). Network analysis is the application of digital tools such as network visualization to expand or adjust our understanding of these relationships.

In my article, I used network visualization, which involved the creation of visual graphs using software called Gephi, to visualize the reception of letters written by and about the English Benedictines. This approach helped to expand our picture of the Brussels Benedictines by making visible the protagonists of religious controversy within the convent and revealing the sheer breadth of the nuns’ correspondence networks in and beyond Brussels. This, in turn, raises important questions about the nature and extent of enclosure for early modern nuns and shows how, despite geographical distance, family members were attuned to events within the convent cloister. In fact, some family members actively intervened in convent disputes in cases where they deemed their family’s reputation to be at stake. This reveals an added layer of complexity to the nature, extent, and consequences of controversy within communities of early modern nuns.

SU: Tell us about your current book project.

BM: My book, Irish Women in Religious Orders, 1530–1700, will be the first comprehensive study of the lives and experiences of Irish nuns in the two centuries after the Reformation. It places the study of this topic firmly within its wider English and European context; the book examines Irish nuns in Ireland and in Europe during this almost 200-year period and in doing so analyzes their experiences through the lens of mobility, migration, and identity.

Some of the key research questions the book addresses are:

- What were the numbers, modes of migration, and destinations of Irish women who travelled to the Continent in pursuit of formal religious vocations?

- What was the nature of the familial and patronage networks that facilitated this migration?

- What were Irish nuns’ particular experiences of emigration and exile?

River Tagus.

Research for this book has been conducted in several archives across Ireland, the UK, and Europe. Central to the European dimension of my study has been the archives of the Irish Dominican convent of Bom Sucesso in Lisbon. Established in 1639, the Bom Sucesso convent holds an important position in the history of Irish religious foundations in Europe, being the first continental convent founded expressly for Irish women. That Lisbon was the chosen location for the new foundation is not surprising. Seventeenth-century Lisbon was a receptive venue for religious migrants from various parts of the European continent impacted by confessional warfare. We know that a well-established Irish émigré community was active in the city since at least the late 16th century.

Bom Sucesso’s founder was the Kerry-born Dominican friar Daniel O’Daly (1595–1662). Throughout the early modern era, the convent attracted patronage from the highest ranks of Portuguese society, including the queen regent of Portugal, Dona Luísa de Gusmão (1613–66), and Catherine de Bragança (1638–1705), later consort of King Charles II.

The history of Bom Sucesso and those women who joined its ranks demonstrates how the history of Irish women religious must be understood within the wider context of early modern European religious, political, and diplomatic history and how migration history is central to revealing the complexities of early modern Irish identity.

SU: You received a Guerin Research Travel Grant for research in Spain and Portugal. Tell us about the collections you visited and what you found. What has been a particularly illuminating find in your research?

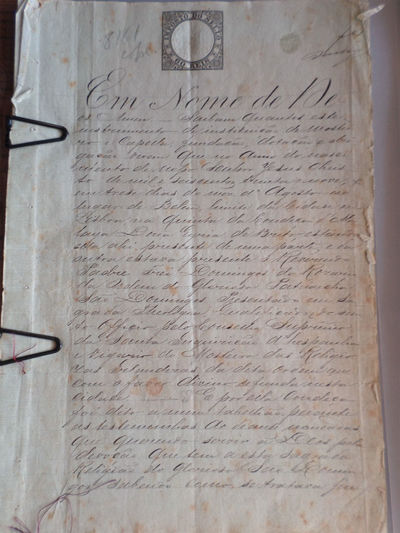

BM: The Bom Sucesso convent archive has been a key repository for my research project. An expansive, multi-lingual repository, the archive holds no fewer than 400 records in Portuguese, English, and Latin, spanning the 17th, 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. These include documents spanning a range of topics, from jurisdiction, governance, and personnel to property, finance, and spirituality.

will, confirming her endowment to the Bom Sucesso

community (BS 15/29). The original is held in the Arquivo

Nacional da Torre do Tombo in Lisbon.

Among these are the will of the wealthy Portuguese countess and widow Dona Iria de Brito, the primary benefactor of Bom Sucesso. From a well-established Portuguese family with connections to the Dominican order, Dona Iria bequeathed her entire estate to the Irish foundation; the family’s summer residence in Belem, on the outskirts of Lisbon, became the convent complex. Her will reveals several important insights about the new foundation as well as the return that she as the primary benefactor expected to derive from her significant endowment. This included the provision of exclusive burial rights at the high altar of the convent church and permission to enter the convent at will. Intriguingly, the countess’s will also reveals the tensions that emerged between the new Irish convent and local Portuguese religious communities who regarded the Irish newcomers as encroaching on the territory and resources of the Portuguese ecclesiastical establishment. This brings to light some key insights regarding the processes of assimilation and acculturation as they related to Irish female religious migrants abroad and raises important questions about the integration of religious migrant communities within the wider ecclesiastical landscapes and structures of early modern Europe.

SU: What’s next for this project?

BM: My book is in the final stages of completion and will appear next year if all goes well. Stay tuned!

I am grateful to the National University of Ireland and the Cushwa Center at the University of Notre Dame for funding the research that made this book possible.