By Carolyn Osiek, R.S.C.J.

St. Rose Philippine Duchesne (1769–1852) was a pioneer missionary from France to America in 1818. She and her four companions were the first women religious to work in Upper Louisiana, the central part of the Louisiana Territory, purchased by the United States from Napoleon in 1803.[1] They arrived soon after the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–1806, and just before Missouri was admitted as a state of the Union in 1820–1821. They thus quickly found themselves as French colonials living in the United States, in an area that was rapidly being populated by Americans arriving from the east, as well as Irish and German immigrants.

Duquette house, St. Charles, Missouri, the first school founded by Philippine, 1818. Courtesy of Provincial Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart.

Duquette house, St. Charles, Missouri, the first school founded by Philippine, 1818. Courtesy of Provincial Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart.

Philippine Duchesne left a legacy of 656 letters, four journals, and several smaller writings, all but one in her native French. She was beatified in 1940 and canonized in 1988. Extensive extracts from her writings were used in a major biography published in 1957.[2] About one third of her correspondence—that with her superior general, St. Madeleine Sophie Barat—was privately published and also translated, but is long out of print.[3] Another biography, written in 1990 from a more contemporary perspective, brought to light different aspects of her writings.[4] Later a collection of the letters of her and her companions in the first five years in America was published in French, but it has not been translated.[5]

Her entire correspondence, a valuable record of pioneer Catholicism on the Missouri frontier, had never been published. For the Society of the Sacred Heart, begun in 1800 and now in 41 countries, her initiative was the beginning of mission outside the founding country of France.

In 2008, two religious of the Sacred Heart—one from France and one from North America—began working together on a complete edition of her writings for the first time, to be published in both French and English in anticipation of the bicentennial of her arrival in 2018. The cooperative venture of working with this material in two languages, on two continents, and across 200 years of cultural change has involved both challenges and rewards. Approval and sponsorship for the project at the level of the international leadership of the Society of the Sacred Heart was soon granted, and since then, each of her letters and journals has been transcribed and annotated, either from the originals or from very early copies made during her lifetime for circulation to communities in Europe.

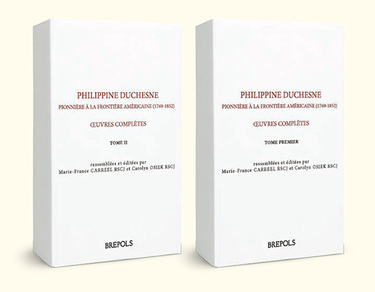

The project team

Marie-France Carreel, R.S.C.J., and I transcribed and annotated the original French. Marie-France Carreel, R.S.C.J., holds a doctorate in educational sciences from Université Lumière Lyon 2. She has taught at the Inter-diocesan Seminary of Avignon, at Institut Catholique Saint-Jean, and at the Catholic Education “Training Center for Primary School Teachers” in Marseille. She first had the task of transcribing all of the writings, most of which are in the General Archives of the Society of the Sacred Heart in Rome. Together we annotated them and wrote introductions (Carreel mostly for France and I for America). After four meetings together in Rome and hundreds of emails, we came to the last stages of checking the text and notes. The French edition appeared in two volumes in December 2017: Philippine Duchesne, pionnière à la frontière américaine : Œuvres complètes (1769–1852).

For the English translation, I collaborated with Frances Gimber, R.S.C.J. The former provincial archivist for the United States Province of the Society of the Sacred Heart, Sister Gimber now does editorial work for the province. Many of the letters had already been translated over the years, mostly anonymously and informally, by various Religious of the Sacred Heart. These translations are more or less good. Each had to be checked word for word. Sometimes they could be used; sometimes not. Most of the letters have been freshly translated.

Sources include the General Archives of the Society of the Sacred Heart in Rome; the Provincial Archives of the United States-Canada Province in St. Louis, Missouri; and sources for St. Louis Catholic Church history, including the St. Louis Archdiocesan Archives, the Central and Southern Province Jesuit Archives, and the Archives of the Congregation of the Mission (Vincentians), DePaul University, Chicago.

Editorial challenges

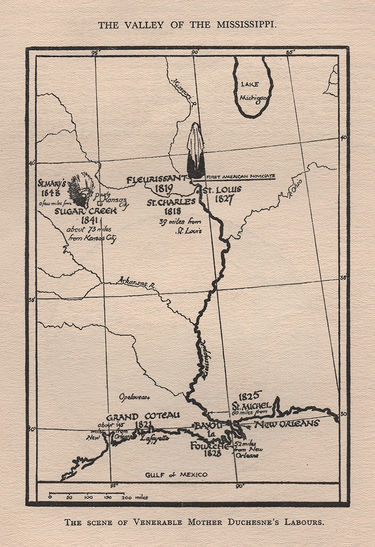

First foundations of the Society of the Sacred Heart in the U.S. Artist: Catherine Blood, R.S.C.J. Courtesy of Provincial Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart.

First foundations of the Society of the Sacred Heart in the U.S. Artist: Catherine Blood, R.S.C.J. Courtesy of Provincial Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart.

Previous collections of the letters were organized by recipient. The editors decided instead to arrange the letters chronologically, in order to see the flow of events and concerns at any given time. This involved meticulous editing by a professional copy editor.

We encountered differences of style, and the fact that the spelling of proper names was haphazard in that era (she never quite learned to spell Mississippi!). We had to ask ourselves: Do we correct her mistakes? Do we standardize for consistent spelling? For the most part, we decided to standardize spelling, though in the case of two of the letters to a Vincentian priest, she got his name so wrong (“Tanon” for “Timon”) that we decided to leave it.

Translation challenges

Philippine Duchesne had a great gift of observation and description. In letters to school children back in France, she gives copious descriptions of the plants and animals of Louisiana that she sees along the river. Some of her reports are fanciful; she either believed what she was told or wanted to pass on certain fantasies to her former students.

She encountered slavery for the first time upon her arrival in New Orleans and lived the rest of her life in states where slavery was legal. How to translate the words usually used for enslaved persons: noirs, Nègre and Negresse? We have used “blacks” and “Negro.” The preferred contemporary term “enslaved persons” brings newer insights that people of her day did not have.

The common term for Native Americans in the French of the day was les sauvages, a word that apparently did not carry the negative connotations of its English counterpart. A literal translation would not convey the intended sense. We opted for use of the word “Indian,” the traditional term, since “Native American” again would suggest insights not yet available to Europeans of the 19th century.

We occasionally came across puzzling words. In a letter from Florissant, Missouri, to a priest in France, Louis Barat, on March 7, 1821, Mother Duchesne writes of the financial difficulties facing everyone in the region, and says On n’entend parler que d’aucans pour paiement de dettes (one only hears of aucans for payment of debts). The word is underlined in her writing, the equivalent of quotation marks. There is a French word, aucans, with a remote 17th-century meaning that has nothing to do with the context. One of the earlier anonymous translators guessed that she was using the English word “auctions” in her French text, which certainly fits the context, and that is probably correct.

Cultural challenges

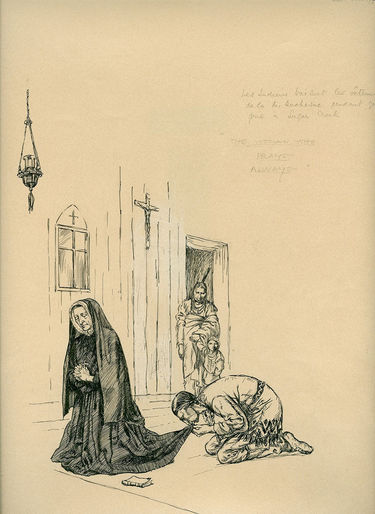

Philippine at prayer, Sugar Creek, Kansas, 1841. Artist: Catherine Blood, R.S.C.J. Courtesy of Provincial Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart.

Philippine at prayer, Sugar Creek, Kansas, 1841. Artist: Catherine Blood, R.S.C.J. Courtesy of Provincial Archives, Society of the Sacred Heart.

The religious brought with them to the New World two ranks—“choir,” for teaching religious, and “coadjutrix,” for sisters who did the domestic labor—as a remnant of ancien régime European social hierarchy, in which the two groups were distinguished by social level and kind of work, and even wore slightly different habits. Within the first year, Bishop Dubourg told Mother Duchesne that this distinction would not work in America, yet she maintained it out of loyalty to the way things were done in France. Because of her own upbringing in the haute bourgeoisie, she was probably incapable of thinking differently. She sometimes complained that the teaching religious had also to do the menial work because of a lack of coadjutrix sisters, and so they did not have adequate time for their classes. She also sometimes made caustic remarks in her letters to France about how the Americans think they are all equal, so that no one will do work they consider beneath them.

That was probably because, paradoxically, they were living in Missouri and Louisiana where there was slavery, which the French religious had not known before. Upon her first encounter with enslaved women in New Orleans, Philippine Duchesne questioned how it could be so. Within a week, she was interacting with enslaved people and appreciating their gifts. Over the years, she wanted to admit black and Native American children to the schools, but was warned that they would lose most of the white students. She wanted to admit women of color into religious life, and was likewise discouraged from doing so. At one point, she wanted to begin something like a Third Order for “women of color,” but that seems never to have transpired. Yet she found that she had to accept some of the social patterns of slavery in order simply to survive in their foundations so as to fulfill their purpose in frontier society.

Being able to read in depth and ponder carefully all the extant writings of a historical person who lived during a very different time leads to insight into the depth of that person’s character. Many things come clear in a vision of the whole. Philippine Duchesne set out from France to serve the Native Americans that she had read and heard about. When she arrived in the Mississippi Valley, she found that this was not going to happen for the next 22 years. Only in 1841, long after the death of Bishop Dubourg who had promised her that kind of mission, did she admit that she had been deceived by him.

At the same time, there are things about a historical figure that can be realized only from contemporary observation. Such, for example, was the stormy relationship of Philippine Duchesne with the Jesuit superior and sometime pastor, Felix van Quickenborne, S.J., about whom she would never say anything negative, but whom we know from contemporaries to have abused the power that clerics held over women religious, to the point of once turning her away from Communion during Mass, and once denying her absolution in confession before the Feast of the Sacred Heart. There was not a word of criticism of him in her letters. Yet the self-revelation afforded us in her writings yields valuable personal and historical insight.

Conclusion

The completion of this project—first in the French edition published by Brepols in December 2017, then anticipated in English for December 2018—represents a significant contribution to the history of the early American Catholic Church and 19th-century missionary religious life. As always, the project turned out to be larger than we could have imagined, but it will soon be complete.

Carolyn Osiek, R.S.C.J., is provincial archivist for the Society of the Sacred Heart, United States–Canada Province, and professor emerita of New Testament at Brite Divinity School at Texas Christian University.

[1] The Ursulines had been in New Orleans since 1727, but had not expanded farther north.

[2] Louise Callan, R.S.C.J. Philippine Duchesne: Frontier Missionary of the Sacred Heart 1769–1852. Westminster, Maryland: Newman Press, 1957. An abridged edition was also published in 1964.

[3] Jeanne De Charry, R.S.C.J., ed. Sainte Madeleine-Sophie Barat/Sainte Philippine Duchesne: Correspondance. 4 vols. Rome: Society of the Sacred Heart, 1988–2000. English translation by Barbara Hogg, R.S.C.J. et al.: Saint Madeleine Sophie Barat/Saint Philippine Duchesne: Correspondence. 4 vols. Rome and Lyon: Society of the Sacred Heart, 1988–1999.

[4] Catherine M. Mooney. Philippine Duchesne: A Woman with the Poor. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist, 1990. Reprint Wipf & Stock, 2007.

[5] Chantal Paisant. Les Années Pionnières, 1818–1823: Lettres et journaux des premières missionnaires du Sacré-Cœur aux Étas-Unis. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2001.