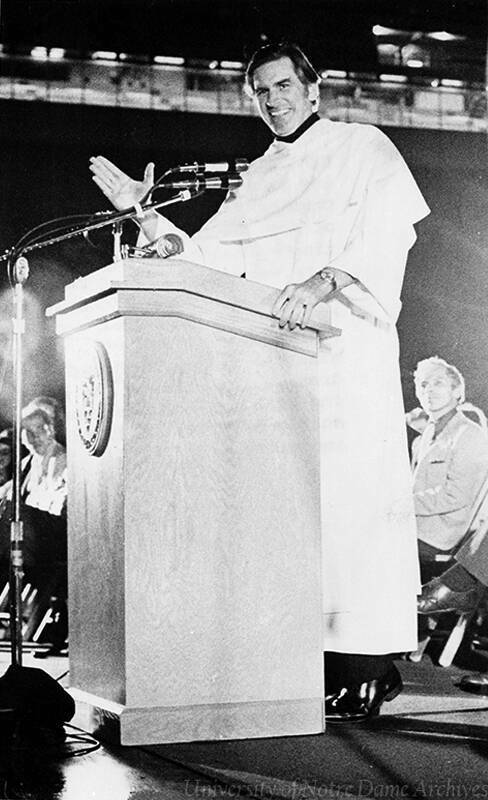

Fifty years ago today—on June 14, 1974—tens of thousands gathered in Notre Dame Stadium for a healing service at the eighth annual International Conference on Charismatic Renewal in the Catholic Church. Leading the Friday evening gathering were Rev. Francis MacNutt, O.P., and Rev. Michael Scanlan, T.O.R., with Cardinal Leo Suenens of Belgium (one of the most prominent advocates for reform at the Second Vatican Council) in attendance. Lasting more than four hours amid intermittent rain, the event was described at the time as the largest public healing service to date for the burgeoning Catholic movement.1 It confirmed Father MacNutt’s reputation as the foremost healing minister among Catholic charismatics. Subsequent years would see MacNutt traveling across the globe and training other ministers; married and excommunicated; and eventually reconciled with the Catholic Church and carrying out decades of continued, ecumenical ministry.

Candy Gunther Brown (Indiana University Bloomington) received a Research Travel Grant from the Cushwa Center in 2023 for a biography of MacNutt, to be published in the Eerdmans Library of Religious Biography series. More recently, she secured a Louisville Institute Sabbatical Grant in support of the book. A historian and ethnographer of religion and culture, Brown’s writing and research have dealt with evangelical print culture and U.S. evangelicalism; global Pentecostal and charismatic Christianity, science, medicine, and religion; and religious practices related to alternative healing, including yoga and mindfulness. In October, Brown will deliver the 2024–25 Cushwa Center Lecture, titled “Francis S. MacNutt and the Globalization of Charismatic Christianity.”

Shane Ulbrich corresponded with Brown in May 2024 about the project and material she has found at the Notre Dame Archives.

Shane Ulbrich: Professor Brown, thank you for taking the time to discuss your project with us. Could you start by sharing a bit about Francis MacNutt? What is the broad outline of his life—which included important moments here at Notre Dame—and from among the many possible candidates you may have considered, what convinced you to write his biography?

Candy Gunther Brown: Thanks for talking with me about this project. When editors of the Eerdmans Library of Religious Biography series approached me asking if I would consider writing a biography, Francis MacNutt immediately came to mind. I had studied, met, and written biographical sketches on a number of Pentecostal and charismatic leaders, but I could think of no one offering unique insight on as many themes, including tensions between doctrines and embodied experiences, reconciliation of Catholics and Protestants, integration of prayer with medicine and psychotherapy, growth and attrition in religious orders, gender roles and clerical celibacy, and the spread of charismatic renewal across Latin America and globally.

Francis S. MacNutt (1925–2020) grew up in St. Louis, Missouri. He received a B.A. from Harvard University and an M.F.A. in speech and drama at The Catholic University of America, and he served as an army surgical technician in World War II. He joined the Dominican Order, took Holy Orders as a priest, and earned Ph.B., Ph.L., and S.T.L. degrees after eight years of Dominican training. In 1967, he experienced baptism with the Holy Spirit among Protestants; this took place a few months after the now well-known Duquesne Weekend, but at the time MacNutt was unaware of events at Duquesne or Notre Dame.

When the National Service Committee of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal formed in South Bend, Indiana, the group selected MacNutt for its first 30-member advisory committee in 1971. They would later add him to the 9-member board of directors in 1978. MacNutt became a regular speaker at the International Conference on Charismatic Renewal in the Catholic Church, hosted at Notre Dame. During the 1974 conference, he led a landmark healing service for a crowd of some 30,000, including 700 priests and bishops, 3,000 Protestants, and visitors from 40 countries. Hundreds of attendees reported healing, notably a 26-year-old blind from birth. MacNutt’s first book on the subject, Healing (1974), appeared in time for the conference. All 300,000 copies of the first edition sold out, and the book was translated into seven languages by 1978. When a crowd of 50,000 Catholics and Protestants converged at Kansas City’s Arrowhead Stadium in 1977, MacNutt gave a plenary address. Throughout the 1970s, he traveled full time across the United States and globally, promoting the Catholic charismatic renewal (CCR) and bringing healing prayer to its center.

MacNutt became a celebrity. Crowds mobbed him, kissed his feet, and compared him to a “living Saint” with “all the characteristics of Christ.” Then, in 1980, he married. The Church refused multiple requests for a dispensation and excommunicated him. Francis and his wife Judith Sewall, a psychotherapist who had converted to Catholicism, founded Christian Healing Ministries (CHM). Together, they spread charismatic renewal among Protestants, medical doctors, and psychotherapists.

In 1993, MacNutt’s long-awaited dispensation came. Restored to communion with the Roman Catholic Church, Francis and Judith renewed their marriage vows and entered a new phase of ecumenical ministry among Catholics and Protestants. In 2007, the International Catholic Charismatic Renewal Services in Rome and the National Service Committee in Washington, D.C. cosponsored with the MacNutts a School of Healing Prayer at CHM headquarters in Jacksonville, Florida. The six-day event attracted 450 attendees—among them 27 Catholic priests—from 42 countries and 5 continents, with translation into Spanish, Italian, and French. MacNutt published his 12th book in 2010: The Practice of Healing Prayer: A How-To Guide for Catholics. He continued praying for the sick nearly up until the time of his death, three months before his 95th birthday. As of 2024, CHM continues to exert a global influence, through in-person events, publications, and the internet.

SU: Some recent efforts notwithstanding (including the work of past Cushwa fellow Valentina Ciciliot), arguably the significance of the Catholic charismatic movement remains to be fully appreciated by scholars of religion. MacNutt stands as a key (if controversial) figure for the movement, which traces its origins partly to South Bend and its influence to Latin America, Europe, and beyond. Is there a quick way—quantitative, narrative, and/or comparative—to frame the significance of charismatic Catholicism in understanding American and global religion? What stands to be gained from giving it more serious, sustained consideration?

CGB: Great question. The first thing to grasp about charismatic (from Greek charism for gifts) Christianity is the deeply interconnected history of the Catholic and Protestant charismatic and Pentecostal (from Acts 2) renewal movements.

One cannot understand the broader shift in modern Christianity toward gifts of the Holy Spirit without accounting for Catholic contributions. There are three specific areas where Catholics made distinctive interventions (in each of which MacNutt played a significant role): first, demonstrating the complementarity of personal spiritual renewal and social liberation from structural oppression; second, drawing popular attention to exorcism of and deliverance from evil spirits or demons (think The Exorcist film released in 1973 and its many offshoots); and third, integrating spiritual and medical approaches to healing.

The CCR first gained public recognition in 1967 after faculty and students (some of whom took inspiration from Protestants) at Duquesne University and the University of Notre Dame reported being baptized with the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues. By 1973, the CCR had spread to 90 countries.

Between 1970 and 2010, Pentecostal and charismatic Christianity expanded at four times the rate of the global Christian and total populations.

Quantitatively speaking, charismatic movements have exhibited extraordinary growth over the past 50 years. In 1977, 2.5 million out of 49 million U.S. Catholics, and 10 million out of 131 million total churchgoers, identified as charismatic. Between 1970 and 2010, Pentecostal and charismatic Christianity expanded at four times the rate of the global Christian and total populations. Out of 2.4 billion Christians, roughly a quarter, or 635 million, identify as Pentecostal or charismatic, and 150 million are charismatic Catholics.

Meanwhile, the geographic center of Christianity has shifted south. In 1900, four out of five Christians lived in the Global North. As of 2020, two of three Christians lived in the Global South. It is not coincidental that charismatic movements have grown most rapidly in regions ravaged by poverty-related illnesses and social oppression. One of the primary explanations for charismatic growth worldwide is an emphasis on charismatic gifts of healings, miracles, and discernment of evil spirits—and the widespread perception that the Holy Spirit is more effective than other natural or spiritual remedies in healing and delivering suffering people from disease and demonic torment. In certain regions, some 80 to 90 percent of first-generation converts point to a personal healing or deliverance experience as leading them to Christianity.

Scholars of American religion can gain a great deal by paying closer attention to the CCR and to charismatic Christianity more broadly. To take one specific example, U.S. Hispanics: In 2022, 44% of U.S. immigrants (20.4 million people) reported Hispanic or Latino ethnic origins. Immigrants account for 32% of U.S. Hispanics; adding the 68% (43.2 million) who are U.S.-born Hispanics, a total of 63.6 million Americans identified as Hispanic or Latino. Hispanic Americans are twice as likely (43%) as U.S. adults overall to identify as Catholics. Among Mass-attending Latino Catholics, 40% report praying in tongues during church services, compared with 24% of U.S. Catholic churchgoers. Among Hispanic evangelical or born-again Protestants, 57% report praying in tongues at church, compared with 27% of U.S. Protestant churchgoers. These figures do not tell the full story, but they suggest that there is a story to tell about the significance of charismatic religious experiences for a large number of Americans.

SU: Expanding on some of that: Could you tell us more about MacNutt’s engagement beyond the United States—links to Latin American Christianity, etc.?

CGB: Father MacNutt first traveled to Latin America in 1970. By 1974, he had visited Latin America 14 times; by 1979, he had ministered in 11 different Latin American countries and territories. By the end of the decade, he had preached and led healing services on every continent; in 1978 alone, he spent 110 days ministering in 31 countries. By contrast to “star” faith healers, MacNutt always insisted on ministering with an ecumenical team that included Protestants, laity, and women.

MacNutt catalyzed the spread of the CCR across Latin America. In 1973, he convened the first Latin-American charismatic Catholic leadership conference, Encuentro Carismatico Catolico Latino-Americano (ECCLA). For five crucial years, this annual event attracted hundreds of priests and sisters from every country in Latin America. MacNutt encouraged priests and sisters to re-envision their roles as “talent scouts” who trained laity to lead retreats and form prayer groups—a vital strategy for CCR growth in areas where the parishioner to priest ratio sometimes exceeded 100,000-to-1. MacNutt led healing services for stadium-size crowds and won favor from political leaders, including the presidents of Costa Rica and Guatemala. He overcame resistance from supporters of liberation theology who had previously viewed Pentecostalism as a “big escape.” He modified Life in the Spirit seminars to integrate prayer for physical and emotional healing with strategic social activism. Both laity and clergy discovered in charismatic renewal the “spiritual fountain” they needed to sustain their work for liberation. As missionary priests and sisters returned to the United States or Europe and as charismatic Catholics migrated to the United States, the shock waves generated by the CCR in Latin America reverberated globally. We are still experiencing the effects today.

SU: You spent a full week at the Notre Dame Archives in December 2023 and immersed yourself in several collections relating to the Catholic charismatic renewal and MacNutt. We’ll have to read the book to find all that you discovered, but what were one or two things that stood out or surprised you?

CGB: I spent a delightful week at the Notre Dame Archives. One of my biggest surprises was the sheer volume and variety of unique materials in the collections. I could easily spend a much longer period of time productively engaged with related materials, which are well organized and skillfully managed by an efficient and kind staff. Although MacNutt collected a large volume of correspondence, manuscripts, photographs, and audiovisual recordings in his personal archives, I found materials at Notre Dame that are available nowhere else. I also found a substantial body of illuminating manuscripts from the Corps of Reserve Priests United for Service (CORPUS)—a group of married priests with whom MacNutt interacted, and from women leaders in the CCR.

SU: In 2020, then-Cushwa postdoc Philip Byers hosted an online discussion with the co-editors of the Eerdmans Library of Religious Biography about the genre’s virtues for helping religious history reach wider audiences. Another postdoc, Benjamin Wetzel, similarly reflected on this site on biography as a useful genre for historians to put forward their work in a broadly appealing, academically responsible way (and to show the enduring value of the humanities). Wetzel has since published in Oxford’s Spiritual Lives series.

Is this your first book-length biographical project? How has that been different, illuminating, or more challenging than other scholarly monographs?

CGB: Biography is what initially drew me to studying religious history. I incorporated biographical studies in my undergraduate honors thesis, my first journal article (and several subsequent articles), and my doctoral dissertation. This is my first book-length biography. I love the genre. There are so many advantages to studying history through the lens of biography. There is really no better way to understand how real people shaped and experienced historical developments or to grasp the complex lived religious dimensions of theological doctrines. It’s also wonderfully convenient to have a built-in scope for time frame and to guide selection of themes and primary sources.

One of my challenges has been to keep reminding myself not to get sucked down into the rabbit hole by fascinating details—as historians we always have to take care not to lose sight of the forest for the trees, but with biography it’s more like pulling up from the underbrush, because there is so much that is intrinsically interesting! MacNutt in particular had such a long, productive, multi-dimensional life and preserved so many records in his personal archives, not counting his publications and other relevant archival and published documents, that it’s difficult to stay argument driven, concise, and not assume that readers will want to know about every tidbit I’ve sleuthed!

SU: We are looking forward to the book—tidbits included!—as well as your upcoming Cushwa Center Lecture. This isn’t your only project at the moment, but what is its trajectory/timeline? Any other efforts you want to mention?

CGB: I am on track to finish writing the book by the end of 2024, thanks to the Cushwa Center Research Travel Grant and also a Louisville Institute Sabbatical Grant for Researchers. I am also making progress—and found useful sources at Notre Dame to further that progress—on a wider ranging book on demonology and deliverance. I hope to finish this second book, which contextualizes MacNutt’s contributions within a broadly comparative (historically, theologically, and geographically) landscape, in the next few years.

Notes

1 Jim Castelli, “Catholic charismatics claim mass faith healings at rally,” National Catholic Reporter, vol. 10, no. 34 (July 5, 1974), pp. 1–2. See also: John Muthig, “Healings Claimed at 1974 Notre Dame Conference on Charismatic Renewal,” St. Louis Review vol. 34, no. 25 (June 21, 1974), pp. 1, 5.

Shane Ulbrich is assistant director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism.

Stay informed about upcoming events at the Cushwa Center by signing up at cushwa.nd.edu/subscribe.